Category Archives: The Voynich Large Plants

Large Plants – Folio 53r

Large Plants – Folio 52v

Large Plants – Folio 52r

Large Plants – Folio 51v

Large Plants – Folio 51r

Voynich Large Plants – Folio 50v

27 July 2020

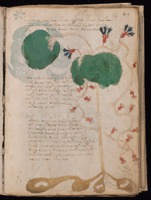

Plant 50v covers much of the lower portion of the folio, with 11 lines of text at the top, carefully arched to avoid writing on the flowerhead. There is a small hole in the skin just under the seedhead but the illustrator ignored it rather than incorporating it into the drawing.

The plant is drawn with a fairly thick root, with bumps along the edges. The leaves are lightly serrated or ruffled (or both) and multiple stalks end in a large rounded head with a whorl of hooks. These characteristics are common in the thistle family.

Other IDs

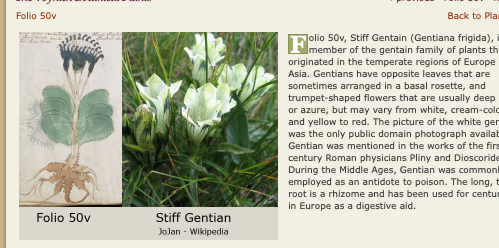

In 2008, Edith Sherwood identified this plant as Gentiana frigida, a small Carpathian plant that grows close to the ground. Gentian has delicate bell-like flower petals and thin hair-like roots. The leaves are narrow and upright, like snowdrop leaves. I don’t think Gentian frigida‘s root, leaves, or flower are a good match for the VMS.

My best candidate for this plant drawing is Arctium (burdock) because it has seedheads with very distinctive hooks. The roots are fairly beefy and the leaves somewhat variable. The only part that doesn’t seem to fit is the bumps on the root. Arctium minus leaves are sometimes rounder and less ruffled than Arctium lappa but leaf shape can be quite variable. The leaves tend to be more rounded when the plant is young. It’s not a perfect match, but it’s much closer to the VMS drawing than Gentiana frigida.

Arctium minus is native to Eurasia but has naturalized in North America. The stalks are sometimes green, sometimes reddish. The shoots and roots are eaten.

Arctium Seedheads

I think the VMS “flower” is probably a seedhead, with hooks at the tips.

Before Arctium seeds are fully ripe, there is a rounded yellowish center nested within a ring of projecting hooks, a characteristic that is well represented in the VMS drawing. The hooks are quite substantial. They will stick to your fingers or clothing, a dispersion strategy used by the plant to spread its seeds when wildlife wanders by. You can think of it as the Velcro® plant. Alex Hyde has captured an excellent macro-lens photo of the hooks here.

Sometimes several seedheads are at the end of a single stalk. They don’t grow together as in the VMS drawing, but perhaps this is a stylized diagram that says, “There may be several seedheads but they all look like this at the top”.

There are other plants with burred seedheads but they don’t match the VMS drawing as well.

- Agrimony has seedheads with little hooks, but the rest of the plant does not resemble Plant 50v.

- Krameria has burrs, but the leaves are small and grow in profusion along the stock, like broom.

- Xanthium (cocklebur) is similar to Arctium, but the seedheads are oblong and grow off the main stem rather than clustering on long stalks.

- Burr grass looks like a stalk of wheat except that the seeds are little star-like burs rather than oval pellets of grain so, overall, it does not match well

Except for the bumps on the roots, Arctium seems to be the best choice. It is reasonably consistent with the VMS drawing and one of the best matches for the hooks.

J.K. Petersen

© Copyright July 2013 & July 2020 J.K. Petersen, All Rights Reserved

Large Plants – Folio 50r

Large Plants – Folio 49v

Voynich Large Plants – Folio 49r

Description

Plant 49r fills most of the page from top to bottom and left to right. In fact, it inhabits the page in a dynamic and sinuous way that conveys an exuberant sense of life. The leaves are rounded, scalloped, and painted a deep green. The stems are light brown, the roots darker brown, and there are two spotted snakes or worms interwoven through the root bumps.

Plant 49r fills most of the page from top to bottom and left to right. In fact, it inhabits the page in a dynamic and sinuous way that conveys an exuberant sense of life. The leaves are rounded, scalloped, and painted a deep green. The stems are light brown, the roots darker brown, and there are two spotted snakes or worms interwoven through the root bumps.

The plant has a viney wavy stem curving around a mostly straight central stem, with flower heads alternately spaced. Some of the flowers at the top are shown in more detail than others, possibly because the petals have not appeared yet (or have withered) on some. The primary color used for the flowers is red or a softened red, with dark blue used to color the parts that look like petals. One flower (or calyx) near the lower left remains unpainted.

There is more text on this page than on many of the plant pages, appearing in three chunks at the top of the page, the middle left and lower left.

Prior Identifications

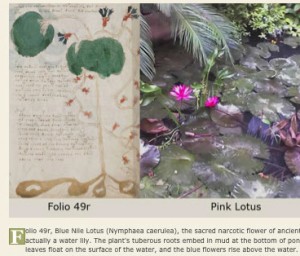

Edith Sherwood has identified this plant as the blue Nile lotus (Nymphaea caerulea), a plant with psychoactive properties that grows in subtropical areas. From an herbal compendium point of view, it would not be surprising to find the lotus represented, the only problem being that the VM plant doesn’t look like a lotus.

Edith Sherwood has identified this plant as the blue Nile lotus (Nymphaea caerulea), a plant with psychoactive properties that grows in subtropical areas. From an herbal compendium point of view, it would not be surprising to find the lotus represented, the only problem being that the VM plant doesn’t look like a lotus.

The 49r flowers have somewhat bell-shaped calyces that are quite different from the spreading elliptical petals of the lotus flower. Nor do the round scalloped leaves look like lotus leaves if you consider that the VMS plant on folio 2v demonstrates that the VMS illustrator was quite capable of drawing a naturalistic plant that strongly resembles a lotus. The roots of 49r don’t look like lotus roots either. Lotus roots are quite distinctive in the way in which the rhizomes spread and leave “scars” from older leaves dropping off.

Other Possibilities

So what can Plant 49r tell us if we examine the drawing a little more closely?

First of all, ask yourself, what kinds of plants have a tall, straight central stem with rounded scalloped leaves near the tops and fairly thick roots? Let’s say for a moment that shrubs and trees are more likely to be shaped this way. Note that there are no flowers along the main stem or within the leaves (note: I suspect the reason the top of the “shrub” is leaning left is because it’s too tall to fit on the page if it is drawn straight up).

Now look at the viney stems that meander around the central stem. They have alternately spaced calyces and flowers and no leaves. I think it’s possible there are two different plants on this page—a vine and its host—and there are not many leafless vines, which helps narrow the possibilities for identification.

Now look at the viney stems that meander around the central stem. They have alternately spaced calyces and flowers and no leaves. I think it’s possible there are two different plants on this page—a vine and its host—and there are not many leafless vines, which helps narrow the possibilities for identification.

Dodder

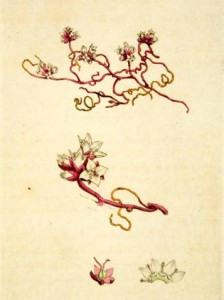

The plant on this page could be dodder (Cuscuta), a spaghetti-like vine thought by some to be related to morning glory. It likes to climb and twine. Dodder is leafless (it has tiny scales, but not leaves as we usually recognize them) and grows mainly in tropical, subtropical, and temperate environments.

Dodder is parasitic and can be a menace to crops. It has earned names like strangleweed and devil’s hair but also less sinister names such as love vine due to its intimate clutching of its host. Sometimes it twines around stems and sometimes it forms a canopy on shrubs or trees—it depends partly on the species of dodder and on the growth habit of the host. Cuscuta europaea will cover a shrub like a big pink blanket.

Dodder is parasitic and can be a menace to crops. It has earned names like strangleweed and devil’s hair but also less sinister names such as love vine due to its intimate clutching of its host. Sometimes it twines around stems and sometimes it forms a canopy on shrubs or trees—it depends partly on the species of dodder and on the growth habit of the host. Cuscuta europaea will cover a shrub like a big pink blanket.

Different species of dodder tend to parasitize particular hosts. Thus, there is flax dodder, tomato dodder, acacia tree dodder, and others. There are also some that are less fussy.

Dodder finds its host through chemical trails—the plant version of a sense of smell. When the seed sprouts, it grows along the ground (sometimes just under the ground) until it reaches a host, then twines itself into the stems or branches. If it doesn’t find a host within a few days or weeks (depending on the species), it will die.

Dodder finds its host through chemical trails—the plant version of a sense of smell. When the seed sprouts, it grows along the ground (sometimes just under the ground) until it reaches a host, then twines itself into the stems or branches. If it doesn’t find a host within a few days or weeks (depending on the species), it will die.

Dodder’s bell-shaped flowers come in many colors, including pink, orange, white, yellow, and beige. Usually the petals are short, but sometimes are long. Sometimes the flower clusters are sparse, sometimes thick.

Relationship to Plant 49r

Which brings us back to Plant 49r and the creatures that look like snakes winding through the roots at the bottom of the page.

Which brings us back to Plant 49r and the creatures that look like snakes winding through the roots at the bottom of the page.

These may not be snakes at all. They may be worms or mythical serpents. But assuming they are snakes, they can mean many things in medieval lore. Snakes are sometimes allegorical, referring to the serpent in the garden of Eden, sometimes they are morphed into dragons, and sometimes are meant to be literal. In herbal manuscripts they usually represent one of the following: the shape or name of the plant (snake-root, snake lily, snake-weed, etc.), the function of the plant (e.g., to treat snake bite), a propensity for the plant to attract snakes, or the fact that the plant is toxic in some way, like we use a skull-and-crossbones.

We cannot say with certainty why the VM illustrator drew snakes winding through the roots, but dodder is dependent upon the host’s root system, since it has no roots of its own, and new dodder sprouts winding along the ground, seeking a host, look very similar to small snakes. Both of these aspects may have inspired the way Plant 49r is drawn.

We cannot say with certainty why the VM illustrator drew snakes winding through the roots, but dodder is dependent upon the host’s root system, since it has no roots of its own, and new dodder sprouts winding along the ground, seeking a host, look very similar to small snakes. Both of these aspects may have inspired the way Plant 49r is drawn.

It is worth noting that C. europaea and C. epilinum (flax dodder) are well represented in European herbal manuscripts. In northern manuscripts, the depictions often show flax or shrubs as the host. In the Mediterranean, trees are sometimes used.

The VMS author had quite a bit to say on this page, considering that many plant drawings have much less text. If the text relates to the plant in some way (we don’t know that it does), maybe the text is longer because both plants are being described.

Summary

I can’t say with certainty that Plant 49r is dodder. If it is, it is more likely to be C. europaea (or some species that is attracted to shrubs or trees), than flax dodder. Across the globe, most dodders have beige, white, or yellowish flowers, but C. europaea is somewhat unique in being pink, the color that would most closely fit the red used in the VM. It’s also possible that the VM color is fanciful, since I’m not aware of any dodder with blue petals, but I’m inclined to take the color fairly literally (within the constraints of 15th century pigments) because the colors of Viola and Ricinus and many of the other plants are applied correctly.

Also, it’s not entirely clear whether there are two plants or one on this page (see Plant 35v for another example of a drawing that may represent two plants), but I felt it was important to provide a dissenting opinion to the idea that it is a lotus plant and to encourage viewers to look more closely at the arrangement of different parts of the plant to consider whether there are, in fact, two, and how that might change our perception of the drawing.

J.K. Petersen

© Copyright 2013 J.K. Petersen, All Rights Reserved