In previous blogs, I described possible influences on VMS Pisces and later added a postscript with some pictures of the alligator gar—a New World fish identified by certain researchers as the inspiration for Pisces. This blog looks at other animal identifications and the otolal “label” near the Pisces fish, which the researchers claim is in Náhuatl.

Janick and Tucker, in collaboration with Talbert and Flaherty, have published articles and a book about the Voynich Manuscript that make significant claims about the identity of the flora and fauna. It will take several blogs to comment on their theories and interpretations, so I decided to start with something simple.

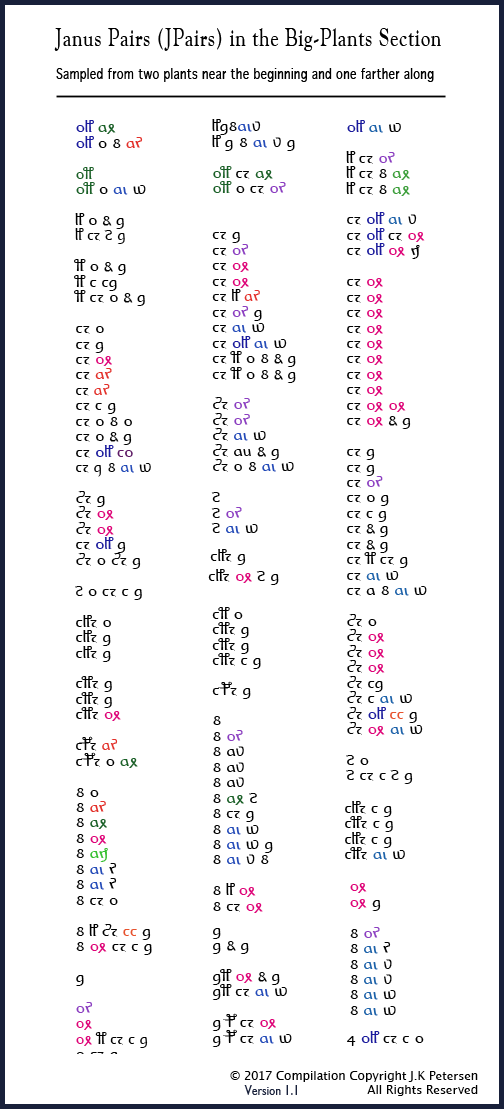

Deciphering VMS otolal

On page 162 of Unraveling the Voynich Codex, the researchers state that the VMS “Pisces” fish, and the large fish with a nymph in its mouth (f70r), are New World fish called the alligator gar. They follow this up with the following decipherment:

On page 162 of Unraveling the Voynich Codex, the researchers state that the VMS “Pisces” fish, and the large fish with a nymph in its mouth (f70r), are New World fish called the alligator gar. They follow this up with the following decipherment:

“The word otolal above the gar can be decoded as ātlācâocâ, according to Tucker and Talbert (2013). Based on similarities to Nahuatl, we suggest that ātlācâocâ might mean “still fished” (ātlācâ = fished, fisherman/spear throwers + oc(a) = still).” —Janick & Tucker, 2018

I don’t know Náhuatl, so I cannot comment directly on this decipherment, but I can pass on what I saw when I looked up ātlācâ in a classical Náhuatl dictionary.

Looking Up ātlācâ

I did a search for atlaca in the Náhuatl dictionary of the National Autonomous University of Mexico. There were numerous hits, but none of them had anything to do with fished, fisherman, or spear throwers. Instead, there was a list of fairly consistent definitions and word combinations relating to bad, ugly, malformed, unwell, bestial, or undesirable, many of them from the 1571 dictionary of the Náhuatl language compiled by Alonso de Molina, a Franciscan priest.

When associated with other syllables or words, atlaca is similar to “mal-” in English, French, and Spanish, which is used to form concepts like malicious, malignant, malady, malformed, and malevolent. There was a reference to mariners, but the word was not specific to sailors, it used sailors as an example of a group of people who are commonly maligned or considered unsavory and the word “ruffians” or “undesirables” could just as easily have been used.

I found some definitions for oc and oca, but I don’t know Náhuatl grammar and can’t judge if it would be correct or usual to append oc or oca to ātlācâ in this way. Perhaps someone who knows Náhuatl will eventually offer an opinion on this.

Another Puzzling Identification

Turning back to the imagery, Janick and Tucker identify this little drawing as a jellyfish:

The image on the bottom of folio 78r… clearly shows the bell and tentacles of a jellyfish…. This tiny zoomorph is crudely rendered and impossible to identify to species level, but there are two possibilities: Chrysaora fuscescens… commonly known as the Pacific sea nettle or the West Coast sea nettle…, or the moon jelly… which is the most common jellyfish in the Gulf of Mexico. —Janick and Tucker (2018, p. 161)

This identification surprises me. Are the researchers ignoring context? I’m pretty sure this is a drain pipe drawn from the front and has nothing to do with sea jellies. There is a drain pipe drawn from the side on the obverse folio:

Large-Plant Identification

Janick and Tucker have suggested that the vine-like plant on folio 49r is Lithophragma affine a delicate plant in the Saxifrage family. They have further identified the snake-like creatures in the roots as a species of salamander (Dermophis mexicanis).

Janick and Tucker have suggested that the vine-like plant on folio 49r is Lithophragma affine a delicate plant in the Saxifrage family. They have further identified the snake-like creatures in the roots as a species of salamander (Dermophis mexicanis).

The ID of Lithophragma affine is problematic.

Lithophragma affine, or woodlandstar, doesn’t grow in the Gulf area. It’s almost entirely confined to California, with a minority of sightings in the northwest corner of Mexico. I don’t know if it had wider distribution 400 years ago, but it seems fairly particular about its habitat and doesn’t like overly hot climates.

Dermophis mexicanis, a legless salamander, lives further south. It is a tropical/subtropical salamander that inhabits lowland moist forests from Mexico to Nicaragua. It feeds on bugs, snails, and earthworms as it burrows through loose soil and leaf litter. It does not eat or dig deep into solid roots, as far as I know.

If it were determined that the VMS was a New World publication, it would still be difficult to find links between D. mexicanis and Lithophragma affine that would inspire an illustrator to combine these geographically separate species on the same page.

Prior Identifications of 49v

I wrote about f49v in 2013. I believe the viny plant may be Cuscuta, commonly known as “dodder”. Cuscuta is a parasitic vine. It does not need leaves for photosynthesis because it infiltrates the stalks and sometimes the roots of its host plant. Some species of dodder wind themselves around the stem, others climb over the host to form a monster umbrella.

I wrote about f49v in 2013. I believe the viny plant may be Cuscuta, commonly known as “dodder”. Cuscuta is a parasitic vine. It does not need leaves for photosynthesis because it infiltrates the stalks and sometimes the roots of its host plant. Some species of dodder wind themselves around the stem, others climb over the host to form a monster umbrella.

When Cuscuta is seeking a new host, a long slender shoot wiggles through the soil very much like a snake. Technically, it doesn’t burrow through roots, but once attached to the host, it does sink fang-like filaments into the host’s tissues to suck out the nutrients. If a new shoot doesn’t find a suitable host within a few hours, it will die.

The VMS plant is leafless, with flowers along the length of the stalk, and it’s quite viny. Cuscuta is much the same. In contrast, the woodlandstar (right) is a white- or pink-flowered plant with long, thin, relatively straight stalks and basal leaves somewhat like Ranunculus. The flowers of woodlandstar do not grow along the stalk close to the base.

While an ID of Cuscuta is not a certainty, it does explain the various features of the VMS drawing more completely than a tropical salamander coupled with a California plant that doesn’t resemble the VMS drawing well except for a small swelling behind the flower petals.

One More for the Road

I don’t want to make this overly long, but I would like to mention one more Janick/Tucker/Talbert/Flaherty animal ID.

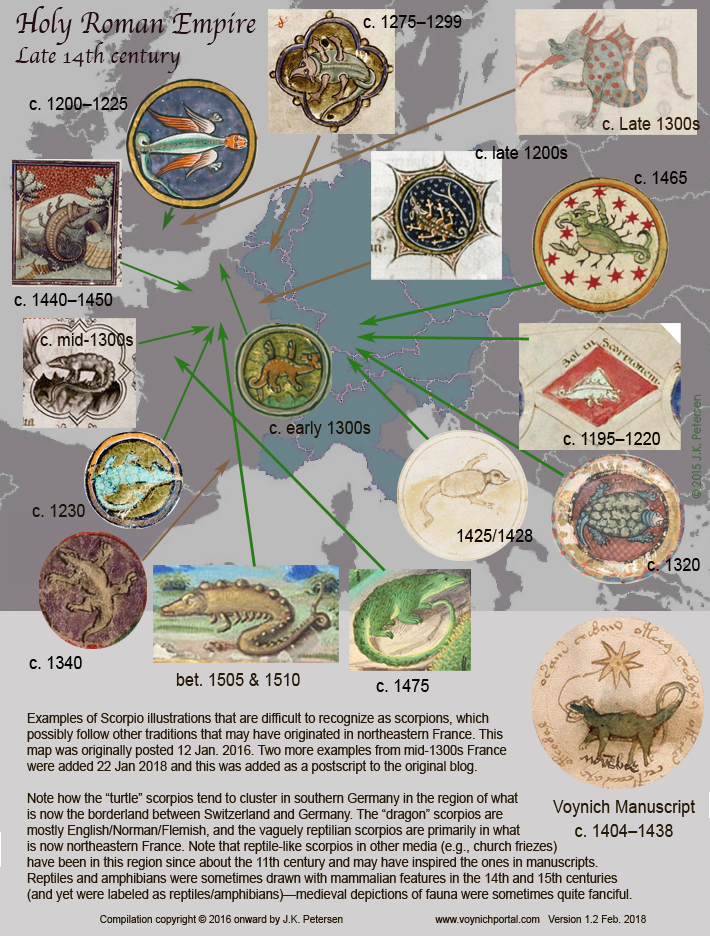

In the past, I have posted images and maps of VMS Scorpius, which is brownish-green and somewhat similar to a lizard or salamander (lizards and salamanders were often drawn with upright legs in the Middle Ages, as the salamander on the right). It’s a little difficult to see the end of it, but the VMS critter’s tail is very long and reaches all the way past its ankle and in between the two hind legs:

It might seem like a strange way to depict a scorpion, but it is reasonably consistent with some of the Scorpius dragon/lizard/salamander zodiacs of the time. Once again, here is a map of some of the non-scorpion Scorpius drawings:

I was very surprised when Tucker and Talbert identified VMS Scorpius as a cat, and that Janick and Flaherty supported this ID. In their words:

I was very surprised when Tucker and Talbert identified VMS Scorpius as a cat, and that Janick and Flaherty supported this ID. In their words:

The dark brown or black cat-like animal with a noticeably long tail on folio 73r… appears to be a jaguarundi (Puma yaguaroundi…) in agreement with Tucker and Talbert (2013), who identified this as a black Gulf Coast jaguarundi (P. yagouaroundi cacomitli). —Janick & Tucker (2018)

First of all, the VMS “Scorpius” drawing is not dark brown or black, it’s tannish-green. The tail is noticeably long, and tapers significantly toward its end and curls in a very un-catlike way. Other hairy or woolly animals are drawn in the VMS with lines to indicate the textured coats, but Scorpius does not appear to be furry. Here is an illustration of a jaguarundi (note the shorter, blunter tail):

Why choose the jaguarundi as an ID for Scorpius when VMS Scorpius resembles other Scorpius drawings much more closely than a New World cat?

Why choose the jaguarundi as an ID for Scorpius when VMS Scorpius resembles other Scorpius drawings much more closely than a New World cat?

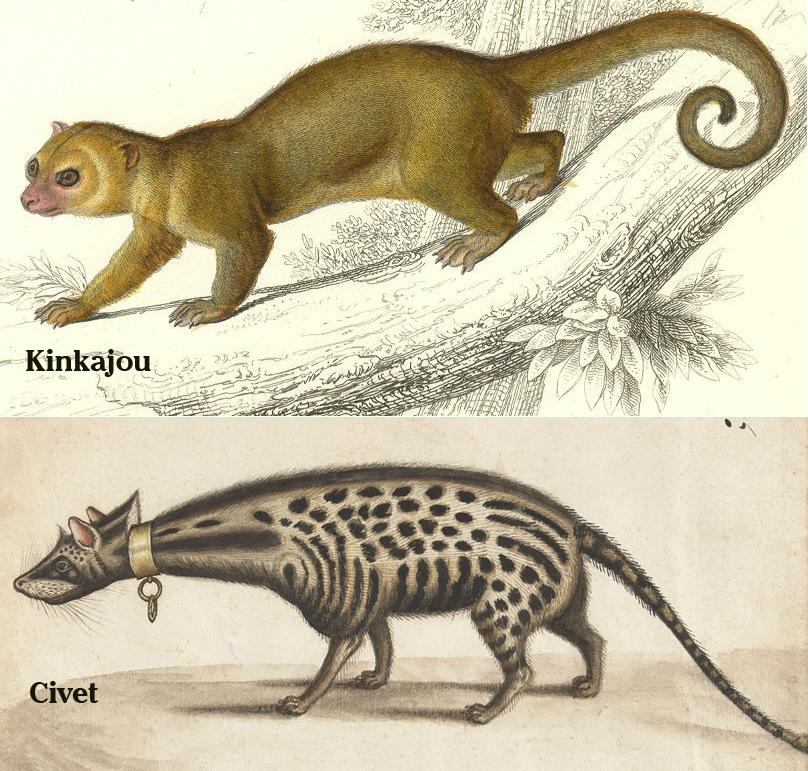

If the researchers don’t see this as a reptile, amphibian, or dragon, as in traditional drawings of Scorpius, then why not include a range of animals that more closely match the drawing, like the kinkajou or civet (note that VMS scorpio has a line of dots on its side, a characteristic more strongly associated with amphibians, reptiles, and civets than with the jaguarundi):

Summary

I’ve said this before, but I think it’s unproductive to associate a crude VMS drawing of an animal or plant with a specific species unless there are strong indicators that it is something unique and thus clearly identifiable (or for which there is an unambiguous exemplar). Most of the VMS drawings are vague and recognizable only through context—a table of possibilities makes more sense.

In their recent book, the authors dismissed the opinions of numerous researchers by referring to “non-published internet comments and chatter“, but other researchers, many of whom have excellent credentials, remain unpublished because research is ongoing and they prefer not to assume too much too soon.

Mistakes are inevitable, in a work of this antiquity and design, so no one is going to get it right every time, but there’s a difference between careful research that goes awry, and research built on faulty premises. If you rush to publication before an impulse is thoroughly investigated, you might mistake a drainpipe for a jellyfish.

J.K. Petersen

© Copyright 2018 All Rights Reserved

![[Pic of Timau village, Italy]](https://voynichportal.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/TimauItaly.png)

![[Map detail Friulian language]](https://voynichportal.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/FriulianMap.png)