The Search for the VMS Glyphs

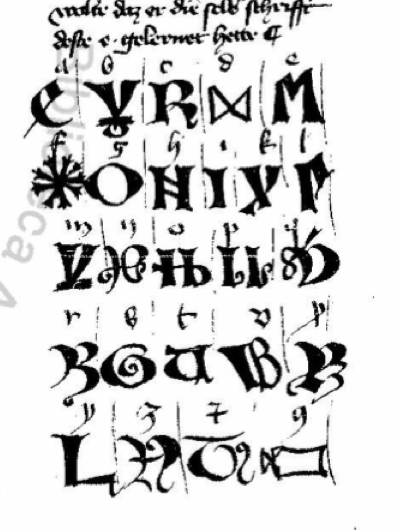

Researchers have speculated for decades about the origins of those funny letters in the Voynich Manuscript.

Researchers have speculated for decades about the origins of those funny letters in the Voynich Manuscript.

When I first encountered the VMS, I recognized most of the shapes from medieval scribal traditions, but I couldn’t read the text, so I combed the world’s archives for examples of other alphabets that might have inspired the glyphs, hoping it might yield clues to an underlying language. Along the way, I discovered certain shapes are found in many scripts—loops, circles, snake-shapes, or sticks with a loop or two, seem to naturally occur in diverse regions. Shapes that look like p, s, g, and ell are particularly common.

In the end, after years of pouring over hundreds of languages and dozens of alphabets, I came back to where I started. The Latin alphabet and scribal abbreviation conventions can explain almost all the VMS characters. I already knew this, but sometimes you have to look around to appreciate what you already have.

I’ve mentioned the Latin origins many times, but I’ve noticed there is still a certain skepticism, and I’ve never posted examples of the entire alphabet due to the enormity of the task (I have thousands of examples and severe time constraints). So, I’ve decided to post it in installments rather than trying to fit it all into one very long paper that might never get finished.

Organizing the Glyphs

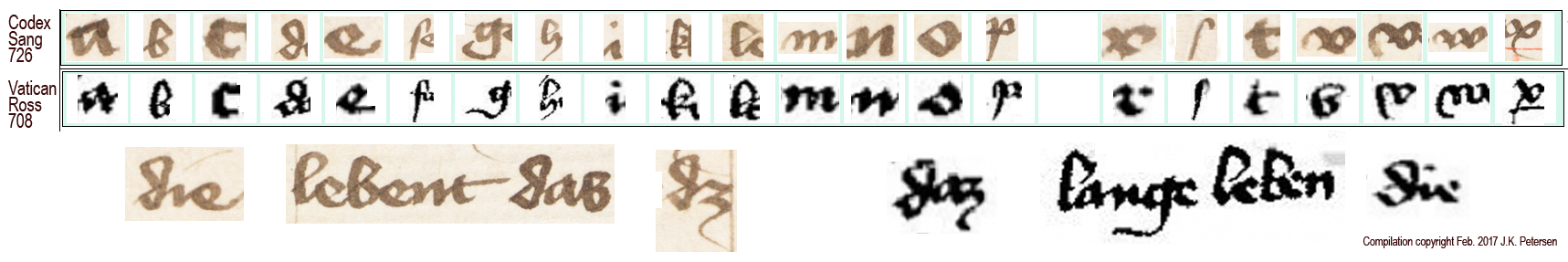

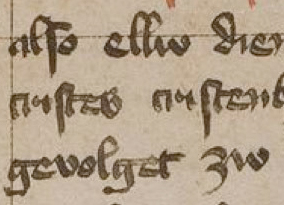

Most people are not familiar with Latin paleography, so I will try to include as many original samples as possible from medieval manuscripts.

Most of the VMS glyphs fall into four categories:

- Latin letters,

- Latin numbers,

- Latin ligatures (two or more shapes combined for ease of writing), and

- Latin abbreviations.

Some glyphs can be classified in more than one category. For example, in medieval script, the Greek sigma is sometimes used as a terminal-s in Latin scripts and is sometimes drawn with the last stroke looped so that it resembles a figure-8. This shape is hard to categorize unless one knows by context whether it is a letter or the number 8. Since the VMS lacks context (the text has not been decoded), I have assigned some glyphs to more than one category (e.g., letter and number, or letter and abbreviation). More on this later when I sum up the individual characters.

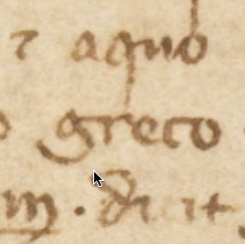

A number of Latin glyph-shapes are borrowed from Greek. Sometimes they mean the same thing and sometimes the shape has been adapted for other uses, as will be illustrated in today’s blog.

The Big Red Weirdo

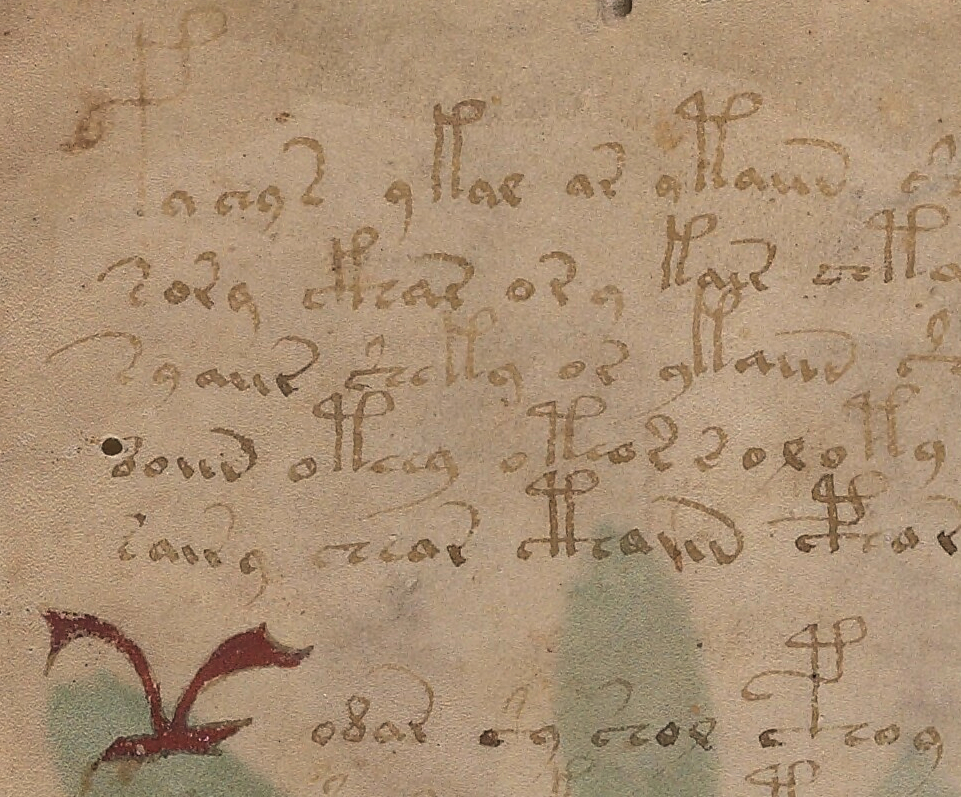

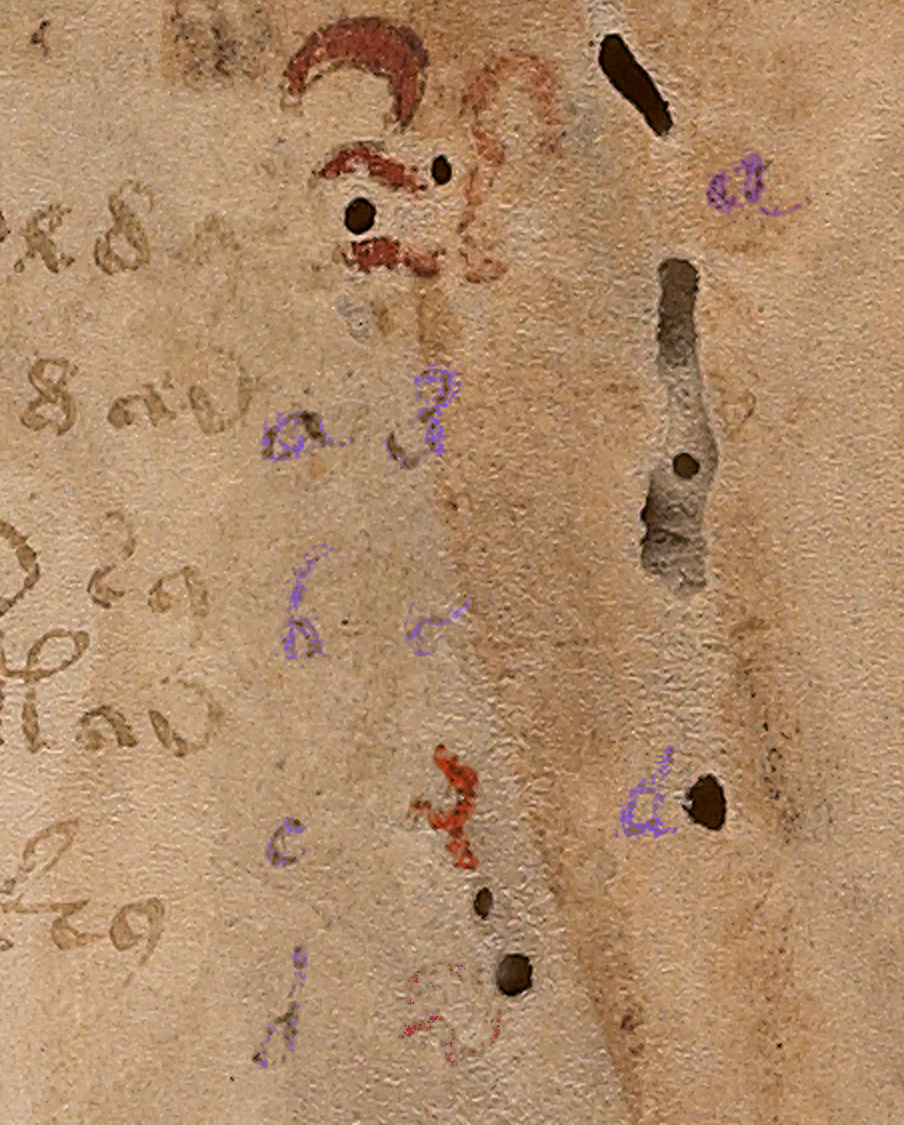

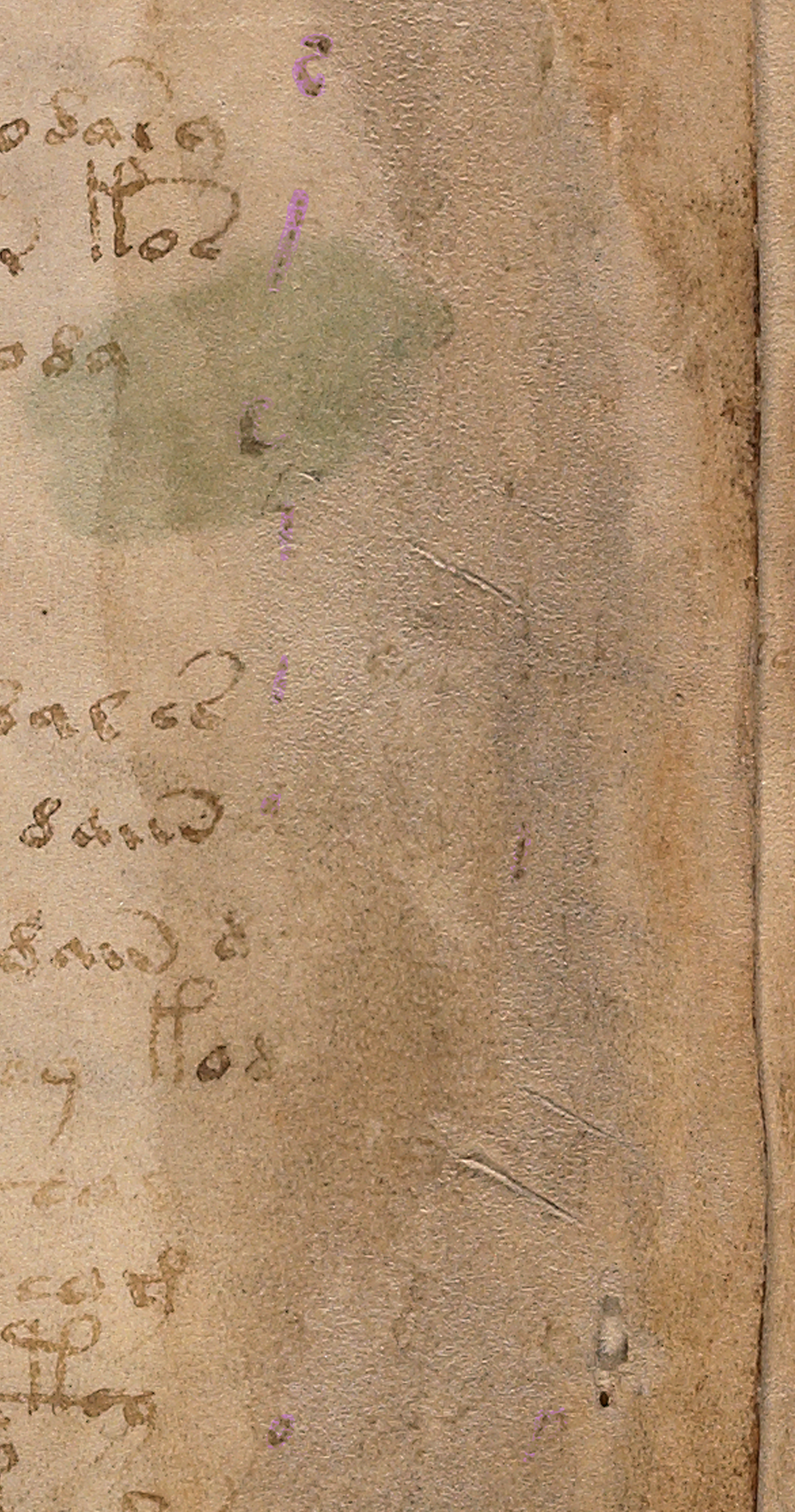

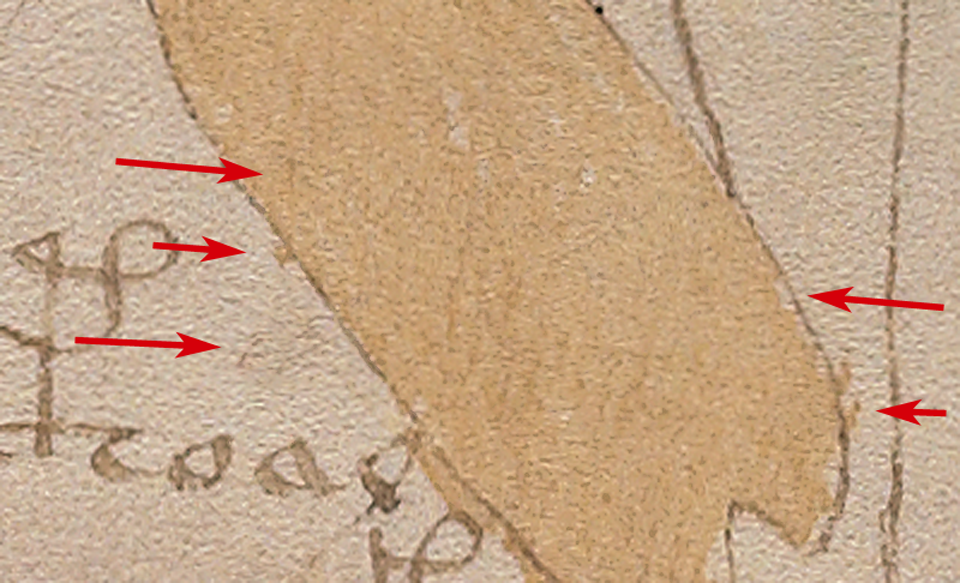

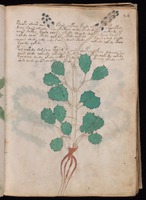

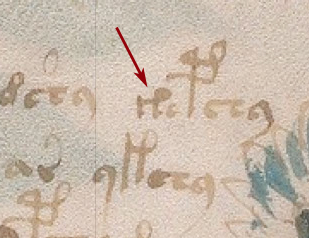

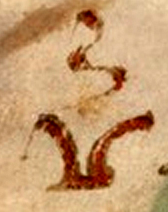

I thought I’d start with one of the iconic shapes in folio 1r, sometimes known as the “bird glyph” or the “seagull” or simply as a “big red weirdo”. This shape is used only once.

The big red weirdo somewhat resembles a bird with a vertical squiggle between the “wings”. I usually call it the seagull glyph.

We learn in primary school that letters have more than one version, and are taught to write both upper- and lowercase letters. In most ancient scripts, there was no distinction between upper- and lowercase, but sometimes the beginning of a paragraph or line would be adjusted for aesthetic reasons or to call attention to something of importance by enlarging the letter, using different colors, or by adding lines, curves, or other embellishments.

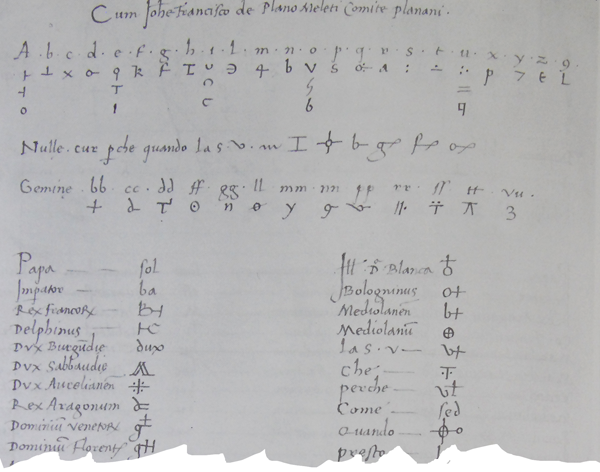

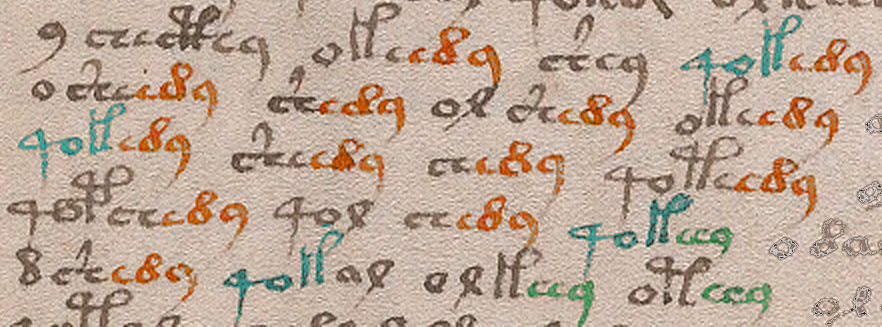

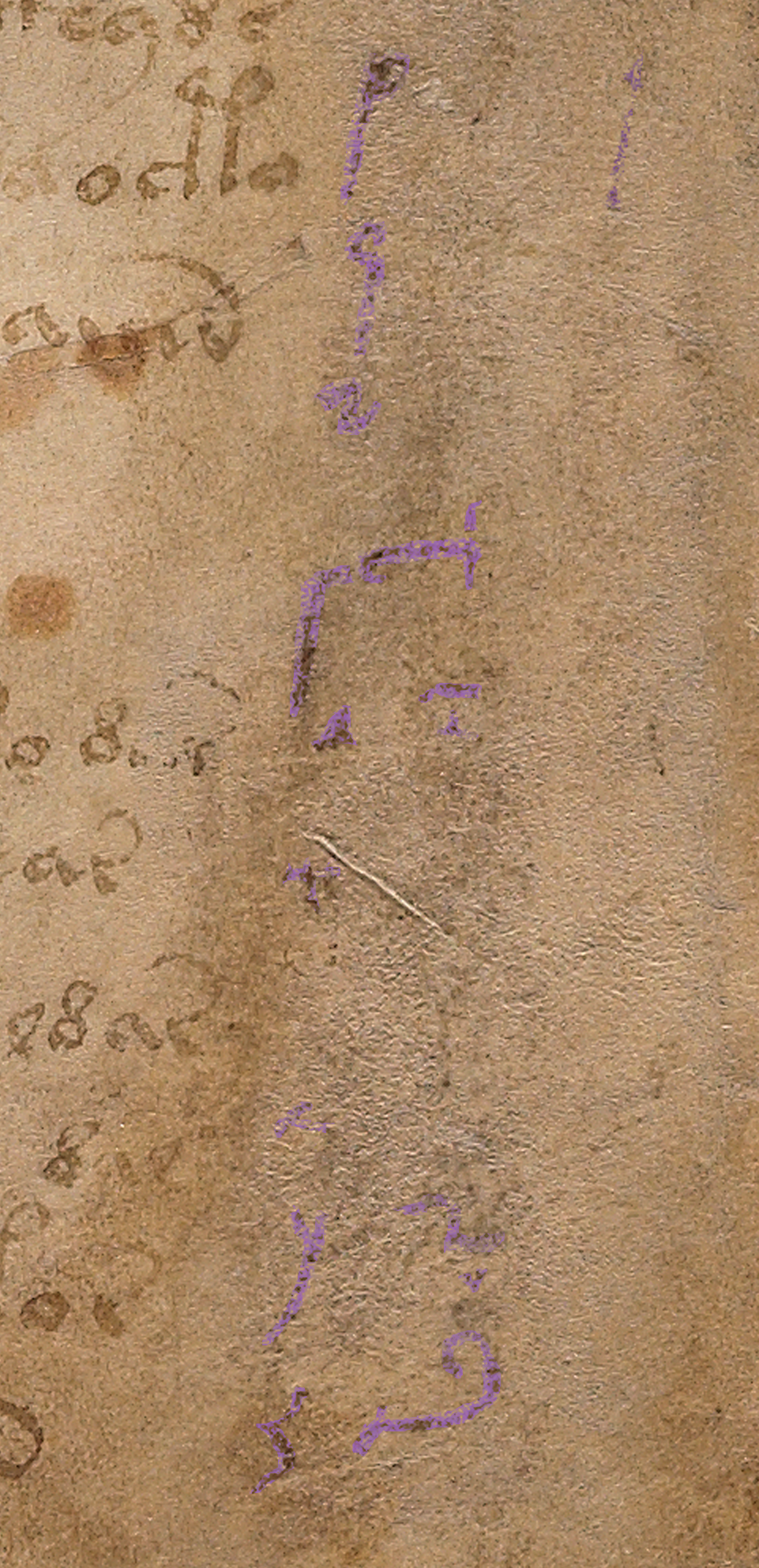

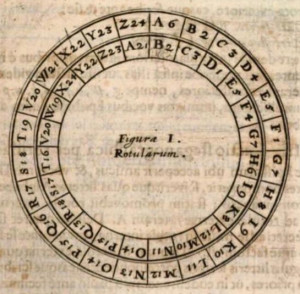

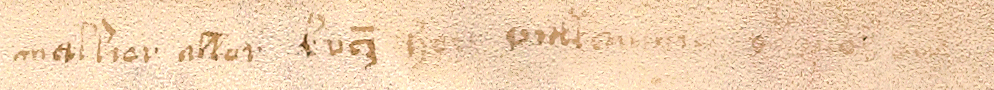

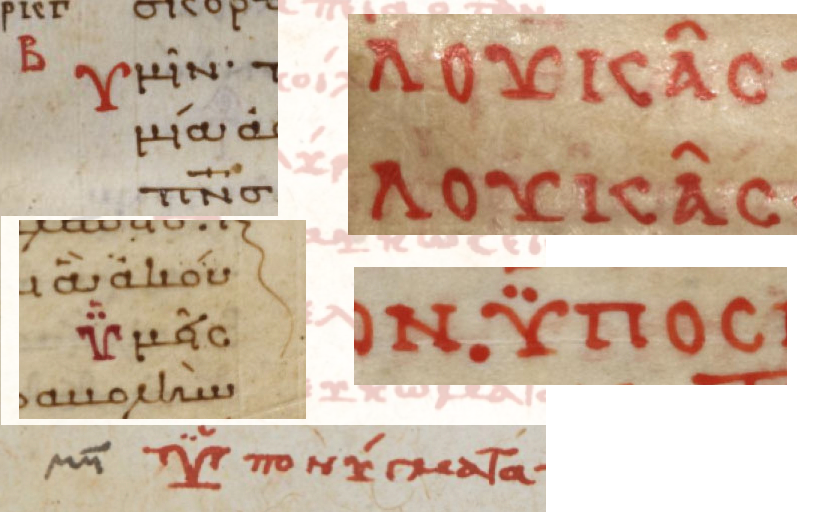

The seagull glyph without the squiggle can be found in old languages that use the Greek character set (a variation of it can be found in Arabic, but much less often). It is not always drawn with the line underneath, but the line is used in certain writing styles or sometimes to create emphasis, as in these examples. Note the double dots above some of the letters. A Latin squiggle doesn’t have the same meaning as Greek dots, but the dots show a precedence for the position of a squiggle in later Latin documents:

These examples are from leftmost columns of new paragraphs (left) and from header text written for emphasis (right). Just as capital letters sometimes have extra strokes to make them stand out from lower-case letters, the Greek letters, such as ypsilon, sometimes had an extra line on the base to give them emphasis. In Coptic Greek this shape (without the dots) represents the letter Ue and, depending on the handwriting style, sometimes the letter Djandjia.

In Latin, the seagull shape usually represents a V, but sometimes it retains one of the Greek meanings. Note that dots have a variety of meanings in Greek. In some cases they are associated with the character (pronunciation or abbreviation), in others, dots can mean that the copied text diverges from the original, a convention that is also used in Latin.

The Seagull Tradition

Latin was a required language for medieval scholars and many also studied Greek, so it’s not uncommon for Greek conventions to show up in Latin texts. Sometimes they mean the same thing in Greek and Latin, and sometimes a shape is preserved but used for different purposes. In some cases, two conventions are combined, as will be seen when I discuss the squiggle.

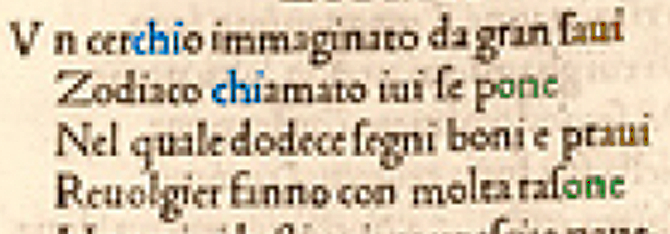

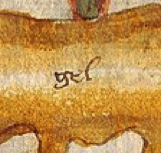

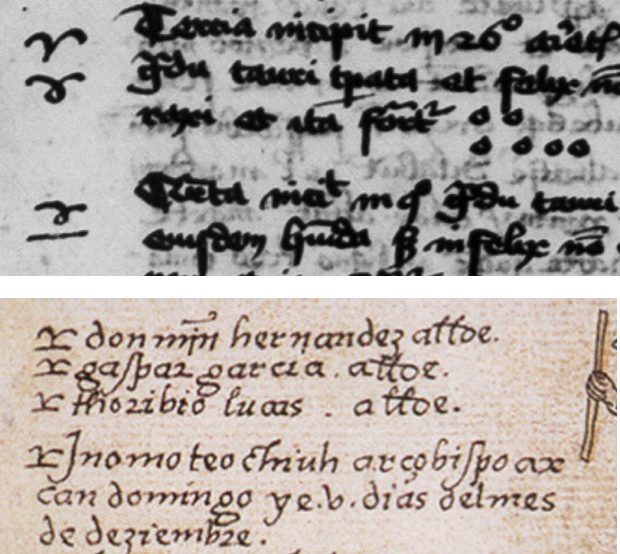

You might have noticed that the seagull shape, when written as it is above, resembles the symbol for Aries. The Aries symbol is ubiquitous in Latin texts on astrology and astronomy, but the Greek convention is sometimes also used to mark paragraphs in texts not related to astronomy. You might notice that the “seagull” shape also somewhat resembles an open book, when the line on the bottom is extended. This, in combination with the way it is used in some Greek texts, might have inspired its use as a pilcrow in certain Spanish documents.

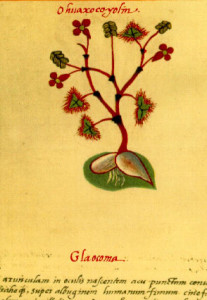

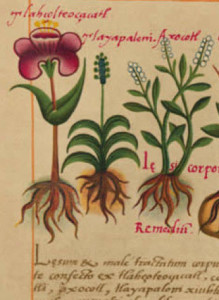

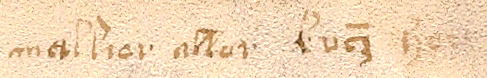

In the above examples, the shape that resembles the Greek letter is used to mark passages in a 15th-century Latin manuscript on astrology, and a 16th century New World document by Spanish missionaries. The shape underwent some minor changes, but its use as emphasis or a topic marker was retained.

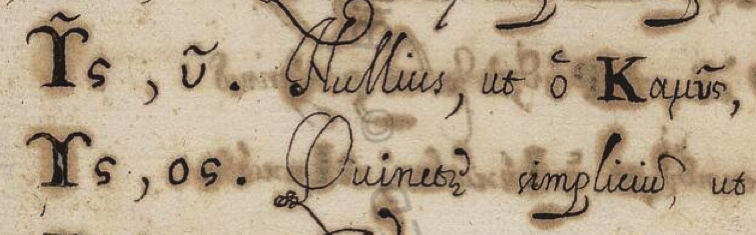

This manuscript combines Greek and Latin, and the character can be seen both with and without the squiggle. Note that symbols above letters in Greek do not have the same meanings in Latin. Greek pronunciation symbols, for example, were not carried into the Latin writing traditions but the use of symbols as abbreviations was prevalent in both traditions.

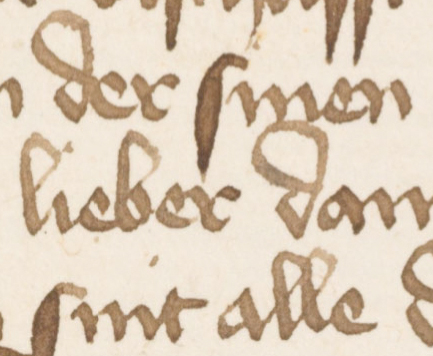

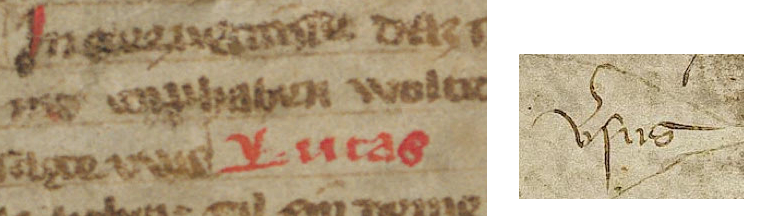

In Latin manuscripts, a seagull shape usually represented the letter V or the letter V plus additional letters. If a squiggle was added, it was almost always an abbreviation. The example on the left is from the late 13th or early 14th century. The one on the right, from the 15th or 16th century.

What About the Squiggle?

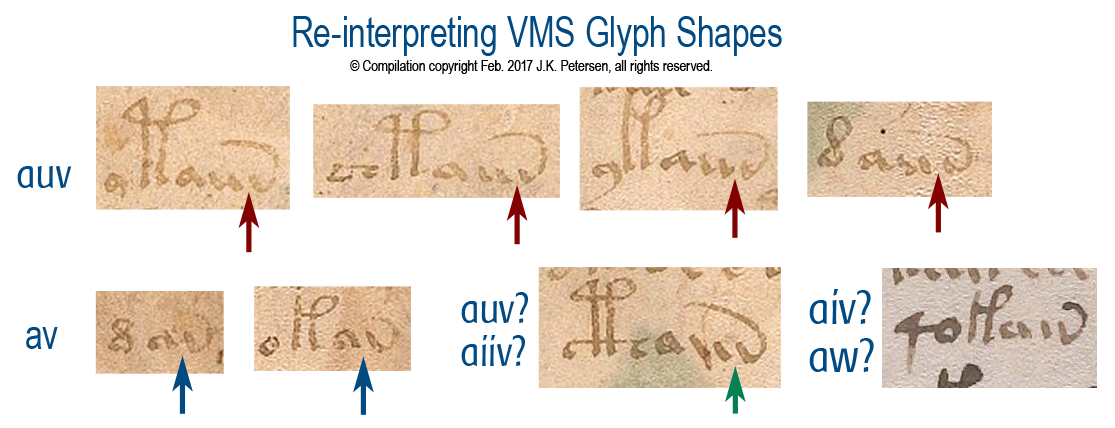

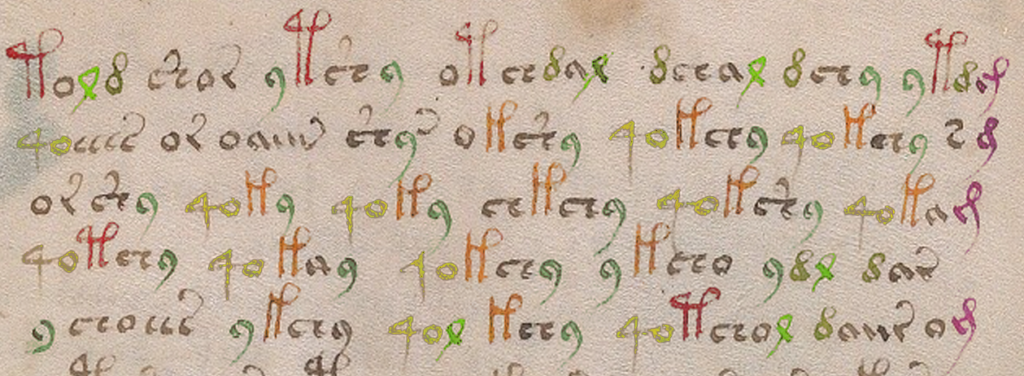

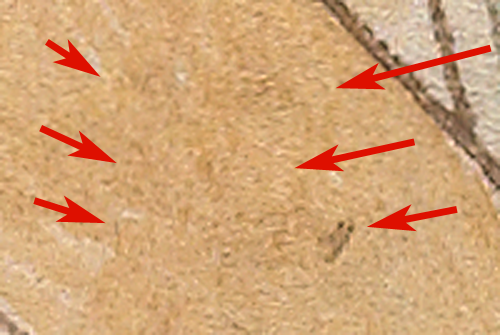

The VMS character is embellished with a flame-like squiggle that sits vertically between the “wings”. This too is a Latin convention, a very common one. It can be drawn as a straight line, a slightly curved line, or a full s-curve, and it can be horizontal or vertical.

The VMS character is embellished with a flame-like squiggle that sits vertically between the “wings”. This too is a Latin convention, a very common one. It can be drawn as a straight line, a slightly curved line, or a full s-curve, and it can be horizontal or vertical.

In old Greek, marks above letters are a combination of pronunciation symbols and abbreviations. In Latin, pronunciation symbols are rarely used and the symbols usually represent a number of abbreviations. You can think of them as specialized apostrophes, depending on their shape and position.

In Latin, the squiggle was particularly prevalent in the 13th and 14th centuries and it was usually drawn in the vertical direction to distinguish it from the shape that represents “n” or “m” which is straighter and almost always horizontal, but it didn’t matter whether an s-curve was horizontal or vertical, the meaning was usually the same—it stood for er, re, or ir or these letters combined with additional letters. In the illustration above, the word on the right is “versus”, with the squiggle standing in for “-er-“.

Sometimes if a squiggle had an extra wiggle, it stood for a degree of something or a series, as the “th” that is added to ordinal numbers. In this case, it was usually horizontal, but not always.

I don’t know what the seagull glyph signifies in Voynichese, but whether one considers it to be textual or an embellishment, the shape is not unusual, especially when it appears like this, at the beginning of a block of text.

Summary

It seems abrupt to end a blog on just one character, but it will take at least a dozen blogs to describe the whole alphabet and a dozen more to describe the relationships between them and their positions in the text (and that’s without going into the actual structure or meaning of the text). As will be seen from other characters, including the more exotic ones, whoever designed the glyphs was familiar with classical scripts and used Latin as the primary source of inspiration (or Latin conventions derived from Greek). This is indicated not only by shape, but by the design of the alphabet as a whole, and by position.

I’ll post examples of the other characters, including a discussion of their behavior, in future blogs.

J.K. Petersen

© Copyright 2017 J.K. Petersen, All Rights Reserved