In Nick Pelling’s Cipher Mysteries blog, he commented on the challenges of parsing VMS text and creating transcripts, and specifically noted:

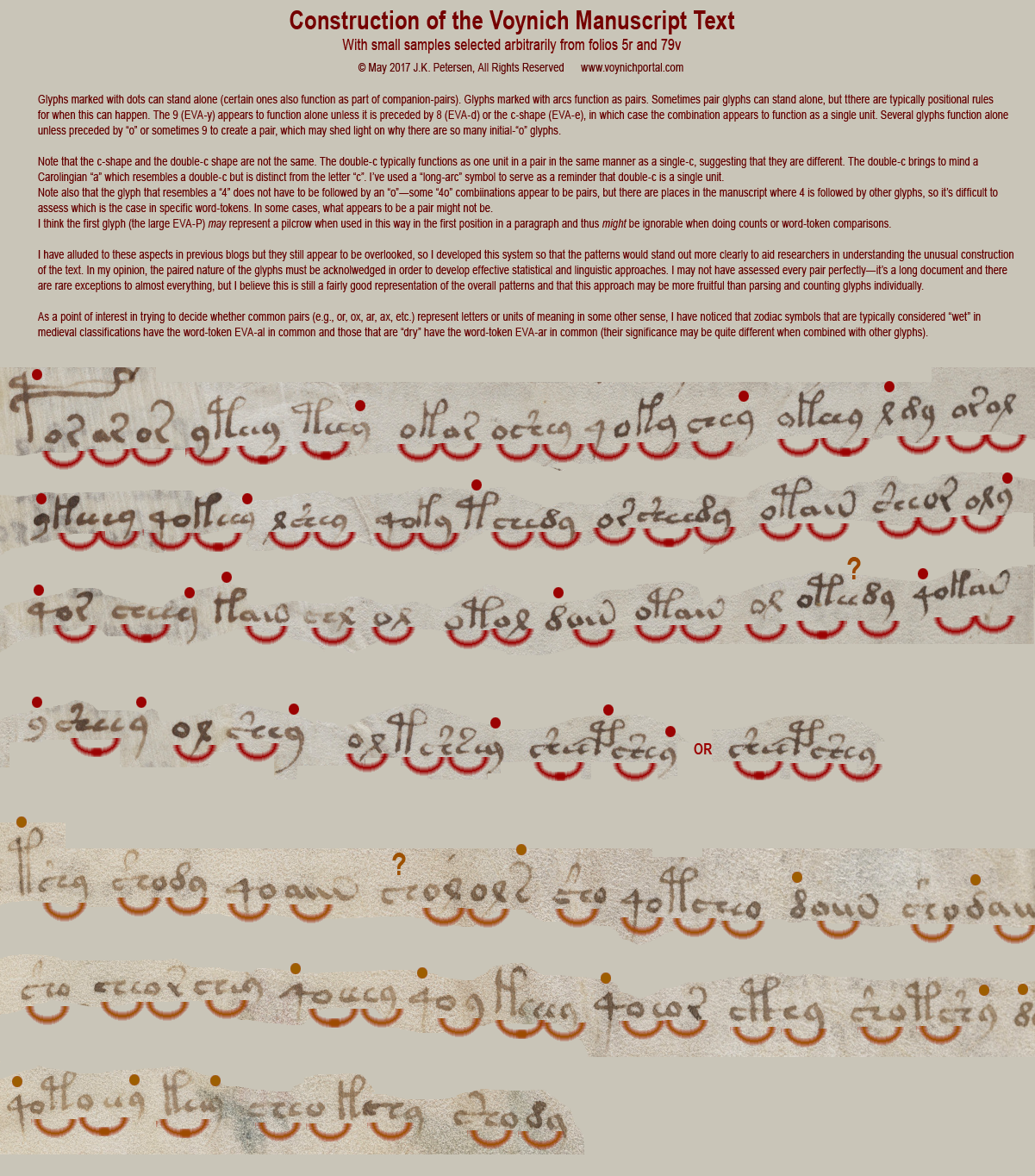

“… a big problem with entropy studies (and indeed with statistical studies in general) is that they tend to over-report the exceptions to the rule: for something like qo, it is easy to look at the instances of qa and conclude that these are ‘obviously’ strongly-meaningful alternatives to the linguistically-conventional qo. But from the strongly-structured point of view, they look well-nigh indistinguishable from copying errors. How can we test these two ideas?”

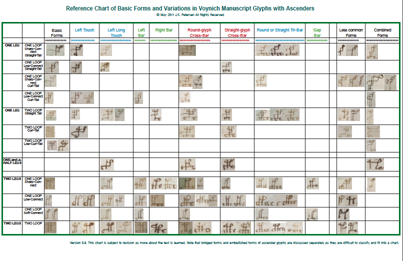

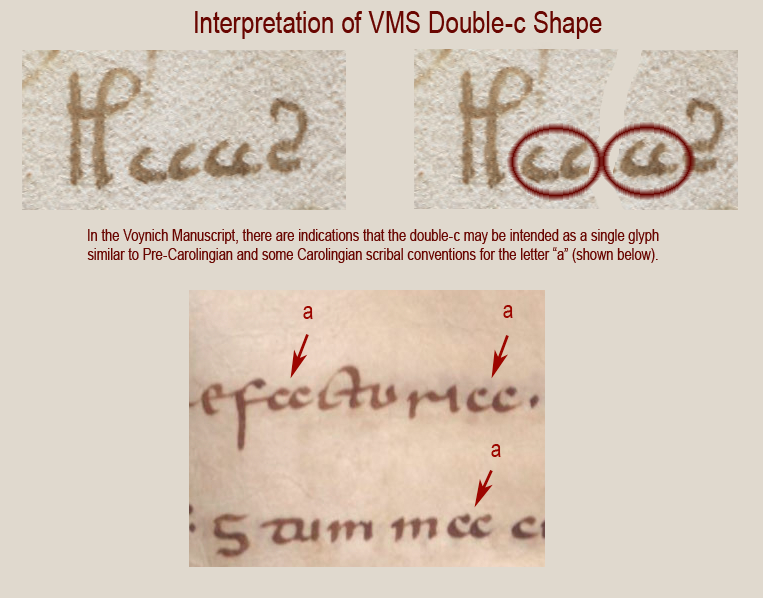

This is indeed one of the challenges in transcribing and understanding Voynichese. Our perception of the structure of the text will be skewed unless one can sort out, to a reasonable extent 1) the exceptions/rare forms, 2) handwriting variations, and 3) copying errors, from what may be meaningful text, so that relevant variations are acknowledged and artifacts filtered out.

The Characteristics of EVA-qo

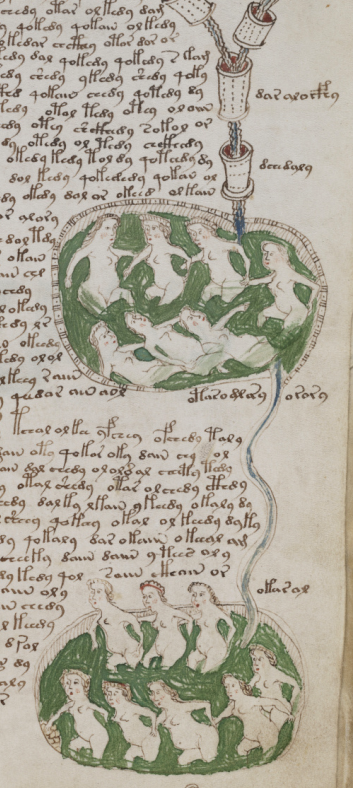

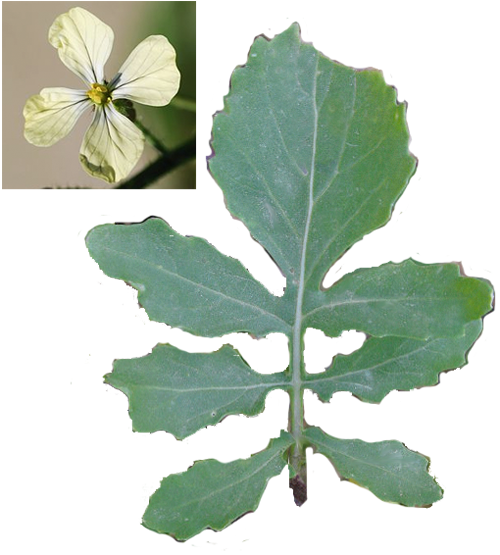

The subject of EVA-qo was touched on in my previous blog, in which I posted a variant 4o image that shows a possible “component” relationship between “qo” and glyphs with ascenders. Prior to that I expressed uncertainty about identifying when EVA-qo functions on its own and when it functions as a pair (I suspect that pairs and singles may function according to priorities), but more examples are necessary to cover the topic in depth.

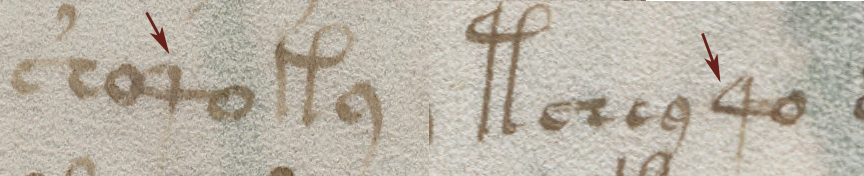

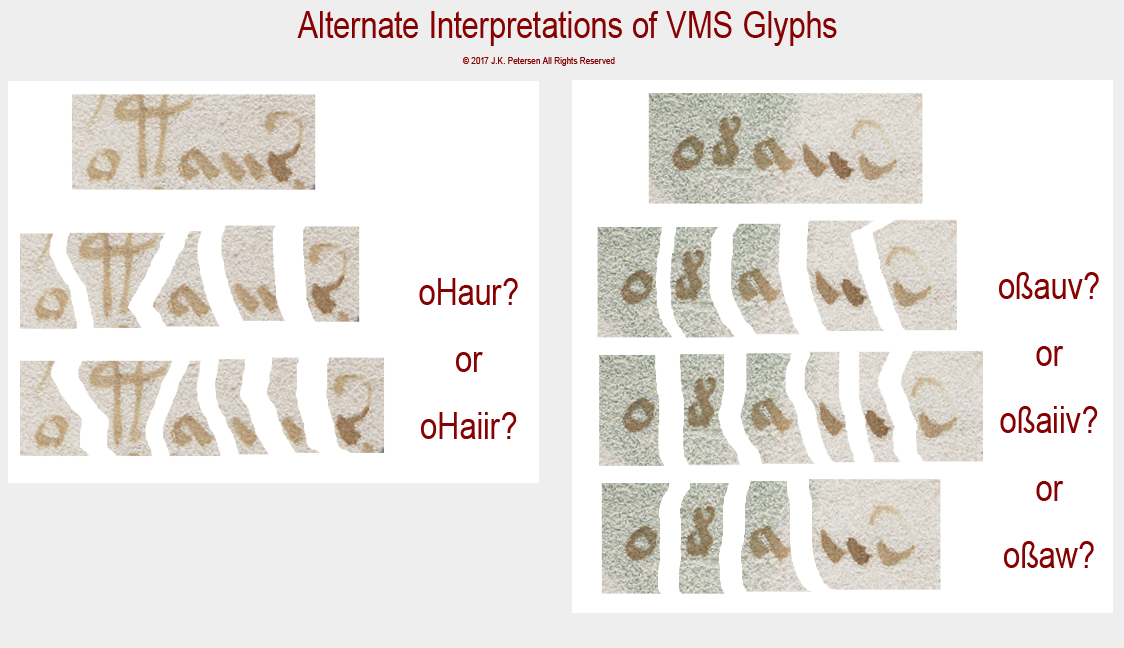

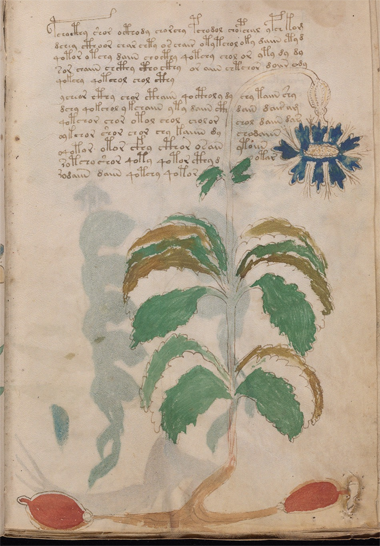

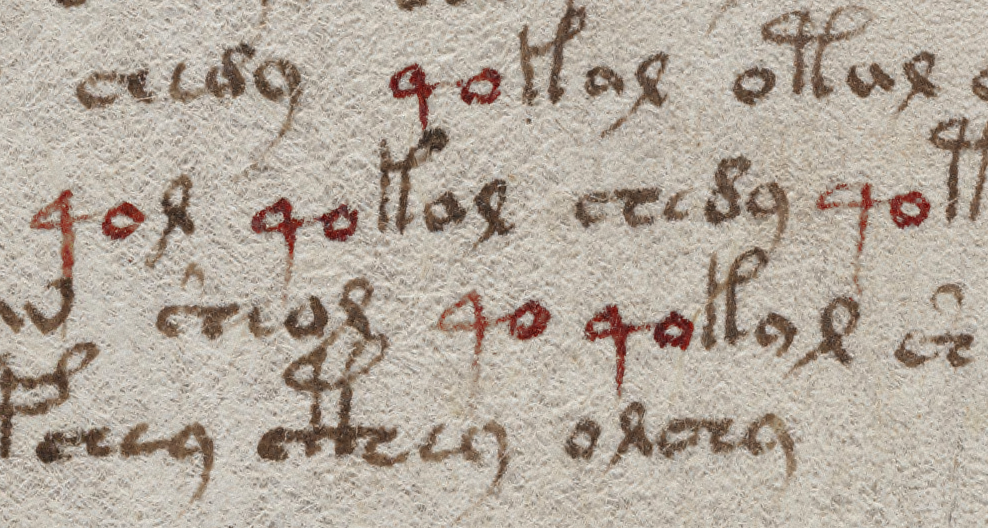

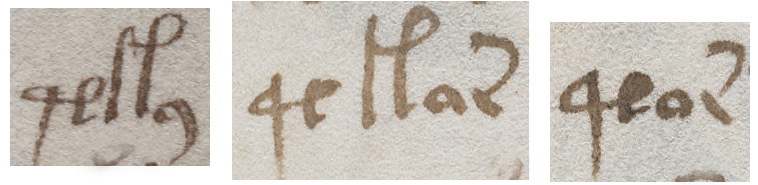

Glancing through the VMS, one will notice that “4o” is a frequent combination. In the following clip, which I chose arbitrarily, one sees several examples of 4o within the space of a few lines. One stands alone (which happens more often than one might think), the others are at the beginnings of V-words. Notice how some have sharp points and others are rounded. Most of them connect to the following glyph:

How does one determine if the 4 and o are intended as a paired glyph, or whether it is simply a common combination such as “qu” in English? Do the sharp and rounded corners have any significance? or the connected/disconnected characters? Note how 4o is frequently followed by an ascender glyph, except for EVA-qol. EVA-ol is one of the combinations that may function as a pair, in which case one has to ask whether 4 can function as a “single” when followed by a pair, according to some rule of precedence, as was noted in the discussion of pair patterns.

At first glance, it might appear that 4 is always followed by “o” and always falls at the beginning of a word. In fact, 4o can occur at the ends of words and occasionally in the middle.

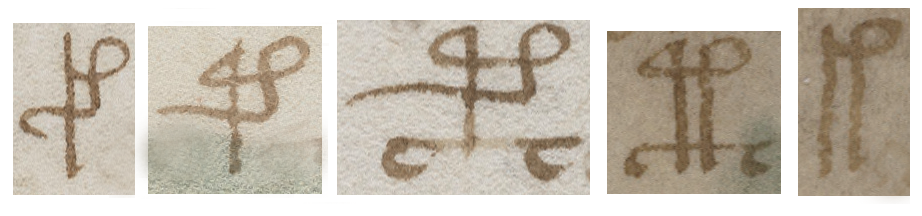

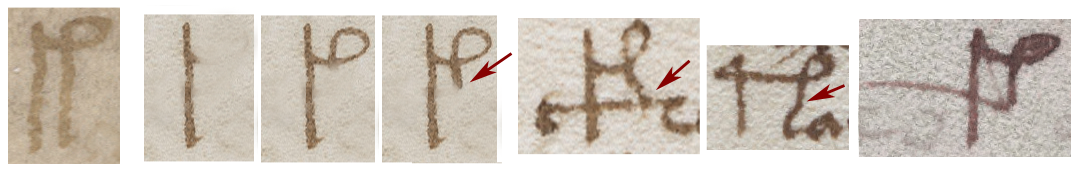

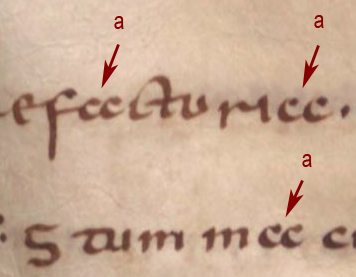

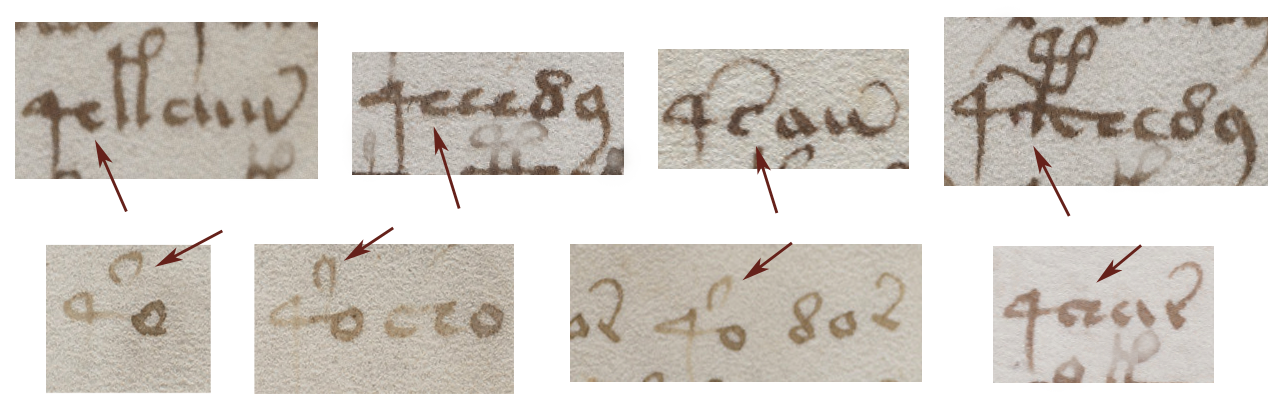

Many characters can follow the 4, including a common Latin abbreviation symbol (which is sometimes straight, sometimes curved). Here are some examples:

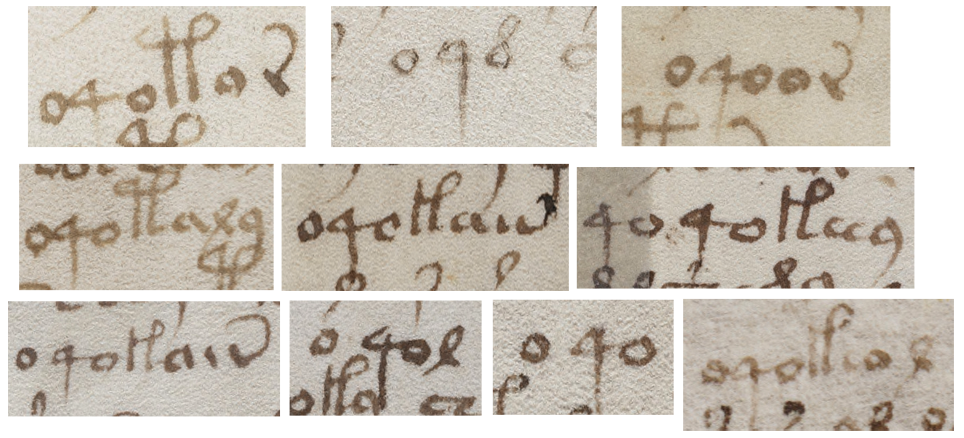

It’s also fairly common for 4 to be preceded by o or 4o, and 4o4 and o4o sometimes stand alone:

It’s also fairly common for 4 to be preceded by o or 4o, and 4o4 and o4o sometimes stand alone:

The o4o words appear mainly in the plant, pool, and starred-text pages, with one in cosmology and one on map rosette #1. There are none in the zodiac or small-plant pages.

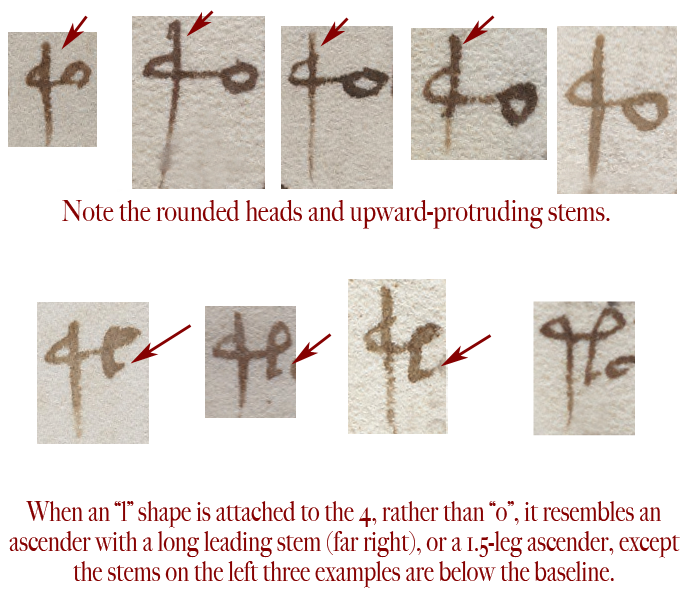

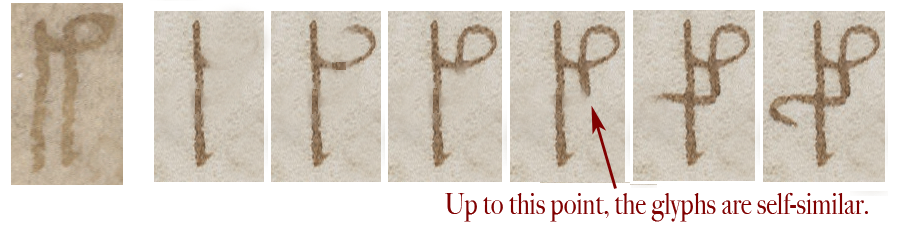

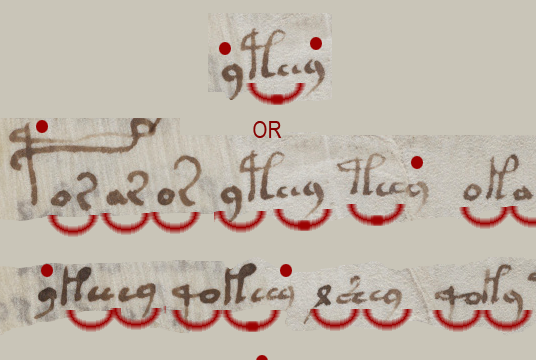

Some variations differ much more than those with straight or rounded connections, as in this example that I’m reposting from the previous blog. It has an extended stem and, below it, a variant that is followed by an “l” shape rather than “o” such that the glyph bears a strong resemblance to a 1.5-legged ascender:

To show this in context, note how a shift in position determines whether this combination looks more like 4o or a 1.5-legged ascender glyph. This isn’t drawn like a malformed 4o or oddball gallows glyph, this looks deliberate, but notice how it falls immediately before ascender glyphs or one that is a common pair, a position typical for 4o:

When EVA-q is followed by a form that looks like a cursive ell, it resembles a 1.5-leg double-looped ascender, except that it is positioned as EVA-q would be, as descending below the baseline.

The 4 glyph doesn’t only resemble the left leg and loop of an ascender, sometimes it is difficult to distinguish a rounded form of 4 from a straight-leg form of EVA-y, both of which look like a Latin “q”.

And Now to the Numbers

The 4 glyph makes its first appearance on folio 1v (the second page, as the VMS is currently bound), paired with “o”, with a line above it. If this were Latin, the line would indicate missing letters in much the same way as we use an apostrophe.

On folio 2r, “4o” becomes more numerous and precedes a variety of glyphs, with ascenders being the most common.

On folio 5r, something interesting happens. There is a unique word on the 6th line (EVA-qokeeey), but if you remove the 4o, it appears as a unique word, without the 4, on another large-plant page (folio 49r) and, without the 4o, on plant page 50v. Similarly, unique word qoToldaiin (folio 4v), without the 4o, appears as a unique word on folio 67r1.

It’s been suggested that unique words are names, but if they were names, wouldn’t someone have decoded them by now? And would so many names, differing only in the first one or two characters, appear on seemingly unrelated pages? If they are names, such as names of plants, wouldn’t they show up elsewhere in the manuscript, rather than being unique? It’s typical of medieval manuscripts to be extremely repetitive, especially if they include recipes, charms, or classification systems—the same names appear with great frequency, especially if they are common ingredients.

I haven’t seen any successful attempts to resolve unique tokens into natural language in any consistent or generalizable way, so maybe they aren’t words. Perhaps they serve a nonlinguistic function. Assuming the spaces can be believed, and they are indeed unique, is it possible that a certain class of word-tokens represents a medieval rendition of pointers, patterns that relate one data location to another?

Variations

The “4o” words are not all unique, some are quite common. For example, qokaiin occurs more than 300 times, mostly on the plant, pool, and starred text pages—it does not appear on the zodiac or rosette pages, which argues against random generation of the text. The 4o words tend to appear only once on the zodiac pages, except for Gemini and Sagittarius, where they occur several times. A unique word on the Pisces page (qoTeeal) appears as a unique word without the q on 69v, a cosmology page.

Summary

If the VMS includes a network of relationships, then it’s essential to determine if the glyph variations are meaningful and whether the spaces are real or contrived. As an example, is the unique word qoToldaiin, on plant 4v, related to the component words qoTol,daiin that appear next to each other on folios 19v, 21v? The first one has a sharp-4 and an ambiguous space. The latter two, have sharp-4 and very clear spaces.

I have much more information on individual glyphs, but this is more than enough for one blog. I’d like to close with a suggestion that “confidence levels” for certain variations be documented in some way (for example, a pointed or rounded q might not be significant, but q with a high ascender is sufficiently different that it might), and a strong suggestion for structuring VMS transcripts to include Quire X, Side X, Folio X in the explanatory sections for each folio. That way, when looking at glyph variations and V-word relationships, it’s easier to see if similarities and differences are tied to physical proximity.

J.K. Petersen

© Copyright 2017 J.K. Petersen, All Rights Reserved