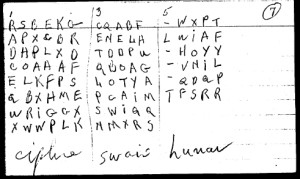

When Mores were Less

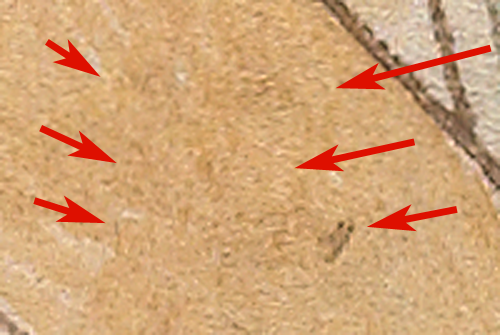

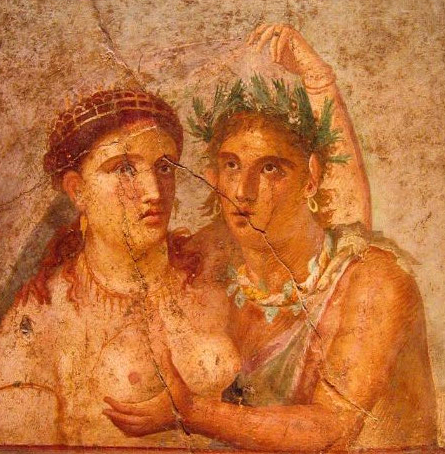

A portion of a wall fresco from Pompeii after the eruption of Mt. Vesuvius, preserved in the archaeological museum of Naples, Italy.

In pre-Christian times, sex and procreation were viewed as natural and commonly depicted on vases, statues, and walls. Everyday objects such as oil lamps or tokens were embellished with images of coitus.

Many ancient Irish places of worship and sometimes even stone perimeters included a carved Sheila-na-gig symbol, a woman not just displaying her vagina, but opening it wide to celebrate fertility, childbirth, and the source of life. In some instances, the Sheila-na-gig warded off evil spirits and it’s been suggested that some served as reminders against excessive lust (you have to wonder if this was a later interpretation).

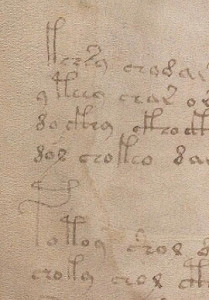

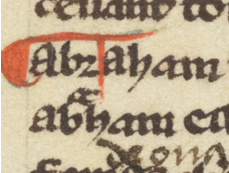

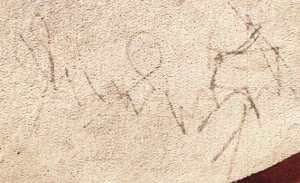

Gradually, Christianity was enforced by kings and embraced by the pious, and sexual repression was justified by stories of Adam and Eve donning clothes after their expulsion from the Garden of Eden. Prohibitions against nudity and sexuality increased and a proliferation of fig leaves appeared on artworks. Sculptures were emasculated with hammers and private parts were expunged from manuscripts with knives and acids. At one point religious teachings were so strict, husbands weren’t even permitted to see their wives nude and a marriage shroud with one small opening between the legs had to be draped over the woman before they had sex.

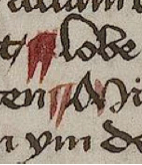

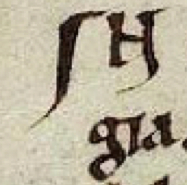

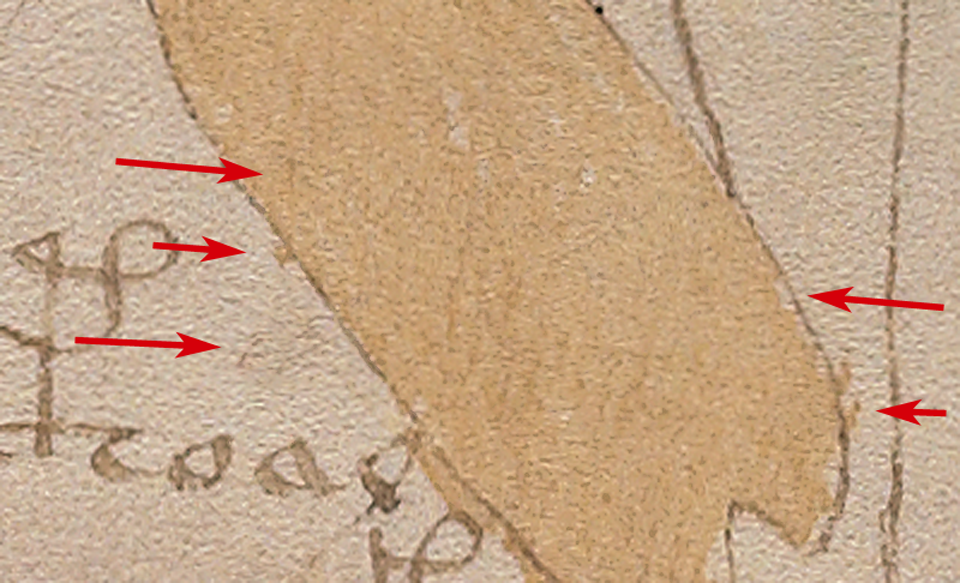

Joseph and Mary c. 1383. By the end of the 16th century, this popular motif openly showing the breast, known as Maria Lactans, was no longer common. Mary giving life to the baby Jesus through breastfeeding was branded obscene rather than as a nurturing part of life.

Usually it was the male sex organs that were removed from manuscripts and other artworks, but in some documents, women’s breasts were scraped away, as well, and it eventually become rare to depict Mary explicitly feeding her baby.

But these prohibitions weren’t as widespread in the early 15th century as they were in later centuries, and don’t entirely explain why some of the VMS sexually suggestive drawings appear to be coy and symbolic. There is plenty of nudity in the VMS, and some regions still retained their Pagan or other non-Christian beliefs into later centuries despite the Inquisition, so it’s possible the illustrator was from a non-Christian culture or an area where Christian prohibitions against nudity were less strictly enforced.

In fact, in the 15th and 16th centuries, encoding information could sometimes get you in more trouble than expressing taboo subjects openly. Medieval academics and alchemists inventing ciphers for recreational reasons, or to legitimately hide trade secrets, risked being accused of witchcraft.

Sexuality in the VMS

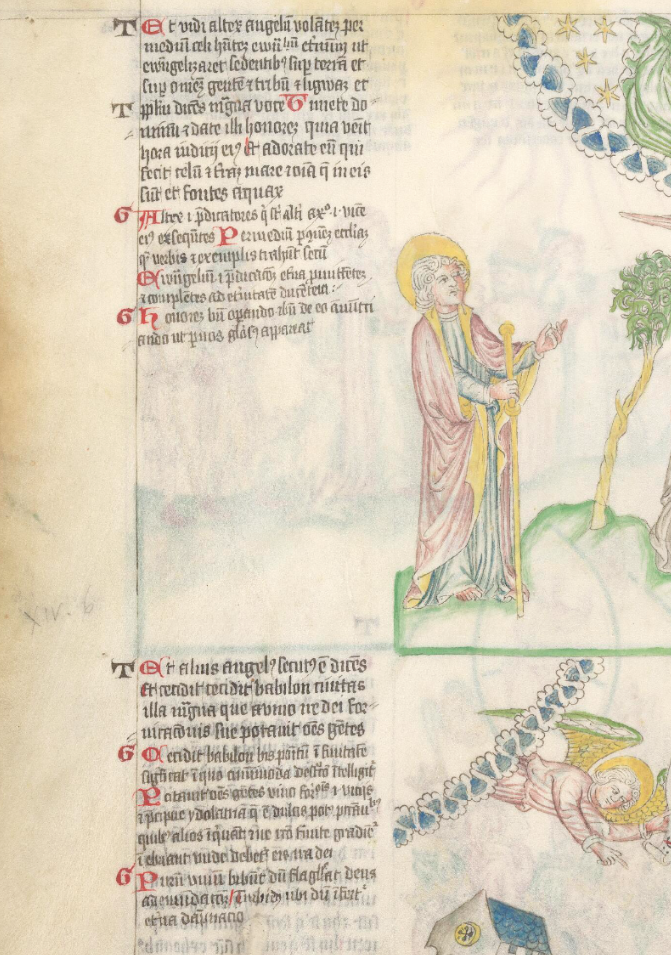

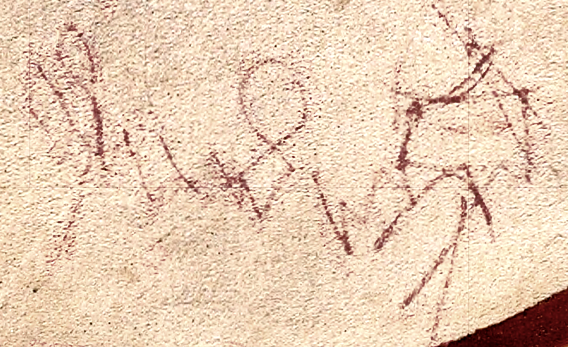

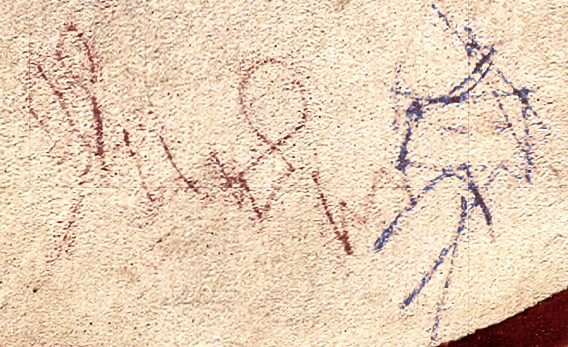

In the VMS, there is nudity on many pages, including the figures around the zodiac circles, but there are no explicit references to coitus. There is at least one image of an ejaculating phallus and some of the male figures are anatomically correct but, other than that, there is little to suggest procreation. Babies are completely absent. A number of drawings do, however, resemble internal organs with nymphs walking all over them. Is it possible to make any sense of these drawings?

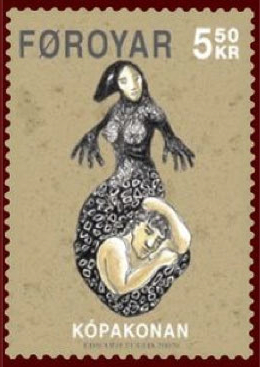

One figure that has particularly captured the attention of researchers is the “mermaid” on folio 79v, in the bottom left corner. It could be a mermaid, a melusine (as described in a previous blog), or perhaps a selkie (right), a mythical sea creature who could shed her seal tail to walk on land.

One figure that has particularly captured the attention of researchers is the “mermaid” on folio 79v, in the bottom left corner. It could be a mermaid, a melusine (as described in a previous blog), or perhaps a selkie (right), a mythical sea creature who could shed her seal tail to walk on land.

The fact that the nymph appears to be separate from the fish-like creature in which she stands seems to argue against most of these interpretations, especially when it’s noted that it’s not only the tail of a fish—it has eyes.

In some ways the VMS image resembles depictions of the biblical Jonah emerging from the fish, but other references to this tale appear to be absent. Perhaps the picture can be explained by looking at other drawings in the left margin of this and the preceding page.

Bodily Functions and Fluids

In medieval philosophy, a great deal of attention was given to organizing the universe according to general principles. Humans invest vast amounts of time trying to simplify a complex universe into simple building blocks in the hopes of understanding it. Sometimes it works; but more often it creates a shaky foundation that is eventually overthrown as knowledge advances.

In medieval philosophy, a great deal of attention was given to organizing the universe according to general principles. Humans invest vast amounts of time trying to simplify a complex universe into simple building blocks in the hopes of understanding it. Sometimes it works; but more often it creates a shaky foundation that is eventually overthrown as knowledge advances.

In the Middle Ages, everything was considered to be comprised of four elements: earth, air, fire, and water (or of five elements, when aether was included). Similarly, in medieval medicine, it was believed everything could be described as hot or cold, wet or dry, and that anatomy could be understood in terms of blood, phlegm, yellow bile, and black bile. Notice that the latter are all liquids and that flowing liquids are prevalent in the VMS.

Interpreting Folio 79

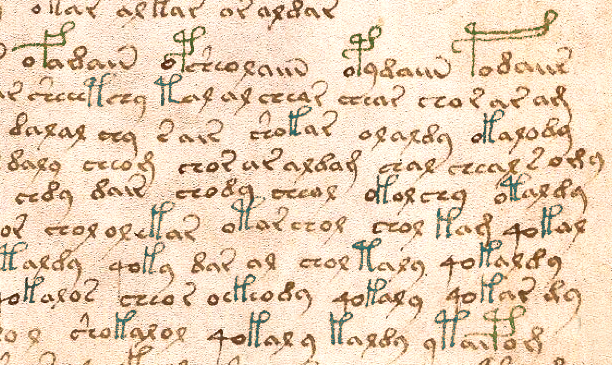

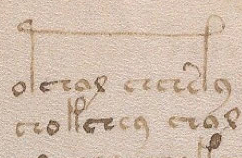

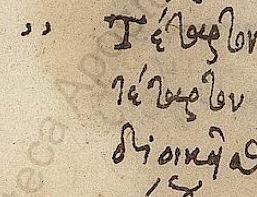

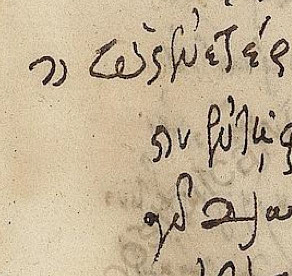

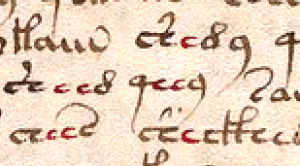

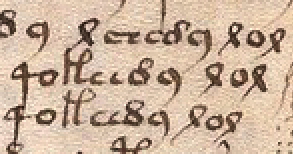

It’s possible that folios 79r and 79v represent internal anatomy. Both pages are similarly organized—several fairly dense paragraphs of text combined with a chain of images running down the left side and across the bottom. On both folios, liquids appear to flow from top to bottom into pools. A distinction has been made by painting the upper liquids blue and the lower pools green.

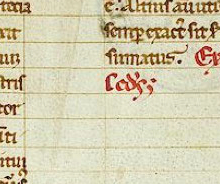

In the first series, the nymphs on the right have shorter hair (or hair that’s tied back), the ones on the left longer hair. Length of hair distinguished a person’s age or marital status in parts of medieval society. In fact, in some cultures, a woman was required to cut her hair and wear hats or a veil when she was married. Note that the double pods near the bottom (see right) are not directly attached to the main “pipeline” of flowing liquids.

In the first series, the nymphs on the right have shorter hair (or hair that’s tied back), the ones on the left longer hair. Length of hair distinguished a person’s age or marital status in parts of medieval society. In fact, in some cultures, a woman was required to cut her hair and wear hats or a veil when she was married. Note that the double pods near the bottom (see right) are not directly attached to the main “pipeline” of flowing liquids.

In the absence of textual confirmation, there are many possible interpretations of these illustrations but if you were to look at this as a diagram of a digestive system, for example, the top could be the esophagus, the next might be the stomach, the third could be ovaries (which are not connected directly to the digestive system) and the last could be the bladder and/or bowels. It’s difficult to interpret what’s going on in the green pool but it looks like a male figure leaning against a log that has two spikes through it (or behind it) and the squire’s arm is wrapped around one of them. One leg is bent forward as though he is walking or bracing his foot on something. Could the log be a phallic reference or something entirely different?

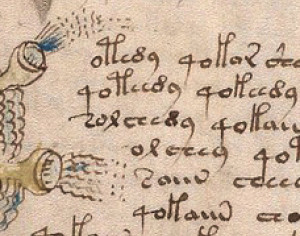

The image on 79v is similar to 79r in that it runs down the left margin, shows flowing liquid in blue, and terminates in a green pool. There is some rare symbology on this page. The upper nymph holds a cross, the second one a ring. There are very few references to Christianity in the VMS, but if the cross were interpreted as Christian imagery, it might possibly stand for Confirmation, a religious ritual common to many cultures in which a pubertal child is initiated into adulthood.

The image on 79v is similar to 79r in that it runs down the left margin, shows flowing liquid in blue, and terminates in a green pool. There is some rare symbology on this page. The upper nymph holds a cross, the second one a ring. There are very few references to Christianity in the VMS, but if the cross were interpreted as Christian imagery, it might possibly stand for Confirmation, a religious ritual common to many cultures in which a pubertal child is initiated into adulthood.

Following this line of reasoning, the second nymph with the ring might mean marriage. A ring was a symbol of marriage in many cultures and notice that the nymph is lying down, as a married woman would lie with her husband.

The third nymph isn’t holding anything, she is dipping her hand into the apparently liquid-filled vessel, but she does have a very round stomach and could be heavily pregnant. The previous nymphs have fairly big stomachs too (as would be expected in the days before Photoshop and liposuction) but this one is even larger than the others. Is it possible that the nymph in the pool, stepping out of the fish’s mouth, is a symbolic representation of birth? If so, what would be the significance of all those other animals?

It might be possible to explain the animals in terms of common creation myths. The story of Genesis is at the beginning of the old testament and thus underlies both Jewish and Christian religions and medieval depictions of creation often show animals emerging out of the ground and out of the water. One of the animals emerging from the water in many European texts is a mermaid or mermaid-like creature. If the concept of creation is doubling as a metaphor for childbirth, it might explain the animals, the fish-and-woman, and the drawings along the side.

Summary

It’s possible the fish represents the birth canal. In many Mediterranean mythologies, the word fish or dolphin also stood for womb or vagina. The ancient Ichthys fish symbol, later adapted by Christians to represent Jesus, originally represented fertility and was the name given to the offspring of Atargatis, a northern Syrian deity who, in turn, was a continuation of the concept of Asherah, the goddess of the sea who, even earlier, represented the concept of renewal and was, at that time associated with trees (as with the tree of life).

It’s possible the fish represents the birth canal. In many Mediterranean mythologies, the word fish or dolphin also stood for womb or vagina. The ancient Ichthys fish symbol, later adapted by Christians to represent Jesus, originally represented fertility and was the name given to the offspring of Atargatis, a northern Syrian deity who, in turn, was a continuation of the concept of Asherah, the goddess of the sea who, even earlier, represented the concept of renewal and was, at that time associated with trees (as with the tree of life).

Without text, it’s difficult to confirm whether these folios represent bodily functions such as digestion and procreation, but I wanted to put forward the idea that the woman-in-fish could be something other than the more traditional imagery built around mermaids, selkies, and melusines. These might be biological symbols running down the left-hand side or perhaps biology and mythology combined.

J.K. Petersen

© Copyright 2016 J.K. Petersen, All Rights Reserved