Ijūin The Strange Formulas in the Voynich

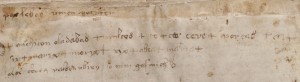

The Last Page of the Voynich was introduced in a previous blog entry and is notable not only for its enigmatic content, but also for the way it differs from the rest of the document—in writing style, content, the balance of the text on the page, the size of the parchment, and the quality of the parchment, which has holes and seams.

The style of most of the writing is significantly different from Voynichese, less round and careful, and perplexingly combined with a couple of words in Voynich script. The relationship between the text and the drawings is not clear, if there is one. The crosses between the “words” is unique to this page.

It’s remarkable that a page with so little content can generate so many questions.

Medieval Charms and Healing Prayers

I alluded briefly to the fact that syllables like oladabad/oladabas and the crosses between the words are reminiscent of medieval charms characteristic of northern Europe. Even the “+” shapes at the beginning of several words (if it is, indeed, an “+”) are common to many charms and combination charms/prayers.

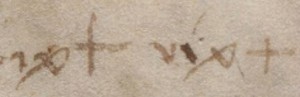

I also mentioned having found a coded word on the fly leaf of Der Neusohler Cato that really caught my attention due to its similarities to the last-page text of the Voynich Manuscript.

I guessed that the coded word at the beginning of Der Neusohler Cato might be a charm/symbol and that it might have a similar function to the text on the last page of the Voynich almost two years before I found time to read about medieval charms. My hunch was based on its sound and character.

I guessed that the coded word at the beginning of Der Neusohler Cato might be a charm/symbol and that it might have a similar function to the text on the last page of the Voynich almost two years before I found time to read about medieval charms. My hunch was based on its sound and character.

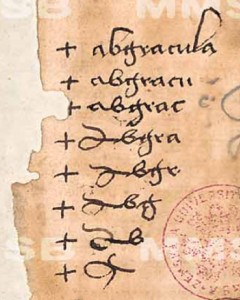

When I finally looked for more information on charms, late in 2012, I discovered a few examples in Leechcraft (Pollington, 2000) with crosses and apparent nonsense words (or words whose meaning has been lost) and a few months later a more specific discussion in Middeleeuwse witte en zwarte magie in het Nederlands taalgebied (Braekman, 1997) which describes charms/healing prayers that contain a mixture of Latin and sometimes incomprehensible “charm” words. You can look up the document online—here are two examples:

In nomine Patris et Filii et Spiritus Sancti. Amen.

+ Ire + arex + xre + rauex + filiax + arafax + N

In particular, note these ending patterns:

+ Ire + arex + xre + rauex + filiax + arafax + N

They’re not identical to the Voynich, but they have a similar character.

And a second example from Braekman:

+ aladabra + ladabra + adabra + dabra + abra + ra + a + abraca + [the person’s name]

The breakdown of the word abgracula on the fly leaf of Der Neusohler Cato to a single symbol made me wonder if the final “coded” symbol was intended to be engraved on a pendant, amulet, or weapon. That might be, but apparently there’s another reason I didn’t anticipate that is mentioned by Braekman. He points out that charm-words are often broken down from larger to smaller units to represent the breakdown of the malady as it subsides. He uses the well-known “magic” word abracadabra (ha brakha dabra) along with another word, ararita, as examples. The crosses are associated with healing and apparently things are helped along by signing a cross in between chanting the magical words.

Many healing charms from the late Middle Ages and Renaissance have a Christian character but it has been my feeling from the beginning that the Voynich Manuscript is not specifically a Christian document despite the occasional cross held in the hands of female characters. The ring and Christian-style cross were common symbols across cultures in those days and may simply be a literary device. Many of the VM drawings have pagan characteristics and the entire enigmatic puzzle-like character of the document points to cultures that keep their secrets close the chest or encode it in some way. The Zarathustrians, Gnostics, and Jewish Kabbalarians come to mind.

Whether the Voynich was encoded because it contained taboo subjects related to sexuality (particularly women’s sexuality) or because it was hard-won knowledge intended to be passed down only to someone “deserving” (perhaps an heir) is not clear. Either way, the secret is still mostly a secret after half a millennium and is providing more food for thought than the Voynich author could ever have imagined.

J.K. Petersen

© Copyright 2013 J.K. Petersen, All Rights Reserved

Feb. 20, 2017 Addendum: I stumbled across a Hebrew blessings phrase, “Ha-Brachah-dabarata” once again, from another source, some time after writing this blog and when I said it out loud (again), it still rings true as the possible origin of A-braca-dabra. Also, some of my research indicates that the charm word Abracula may be derived from the name Abraham (pronounced with a hard-h that sometimes gets transcribed as a hard-c).