This plant ID was visible for about a week in 2013, but I took it down (along with numerous others), because I was concerned about giving away too much of my research. As with many Voynich newbies, I thought I was on the verge of cracking the VMS. I now know the challenge is much greater than I anticipated.

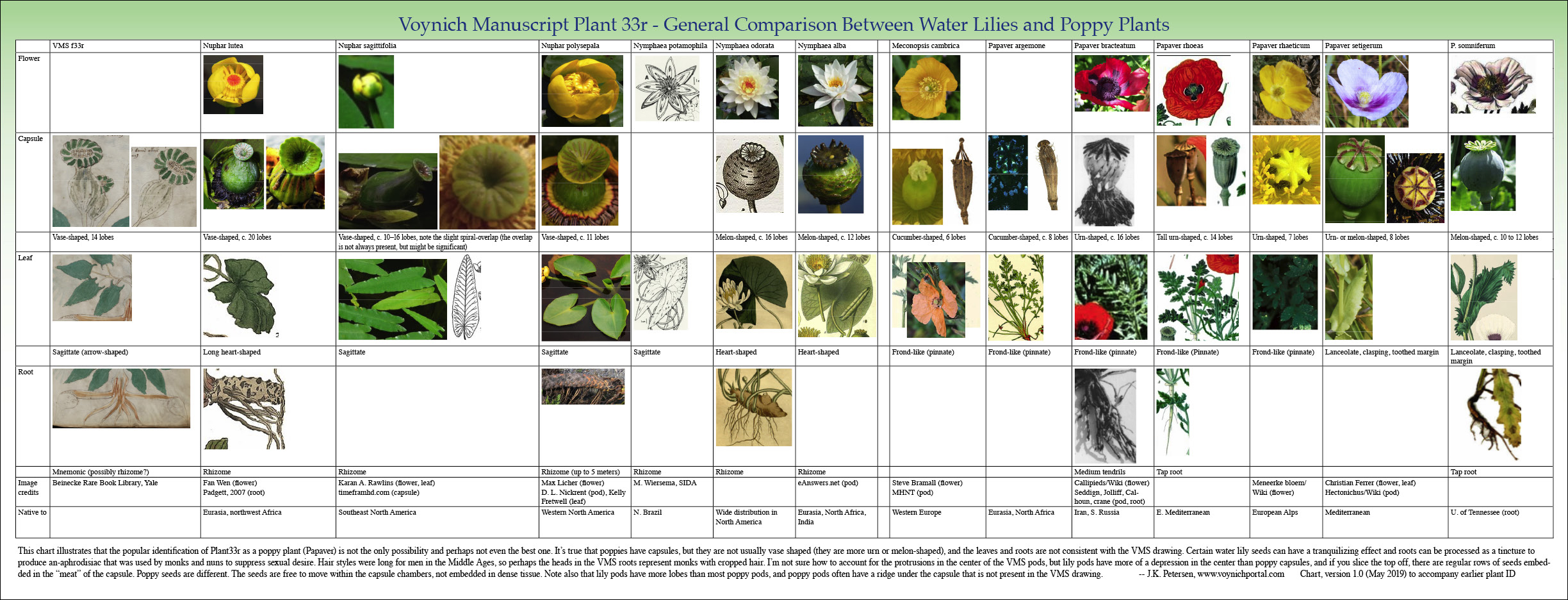

What follows is the original post from 2013, but I have converted the pics to .png and added a May 2019 chart to illustrate my choices because I discovered over the years that my favorite ID has never been mentioned by anyone else. The popular favorite is Papaver (even a Finnish botanist suggested Papaver), but I don’t think it’s Papaver.

As a lone voice crying in the wind, I was worried there might be resistance to my idea if I didn’t add some good illustrations, so I have posted an addendum at the bottom…

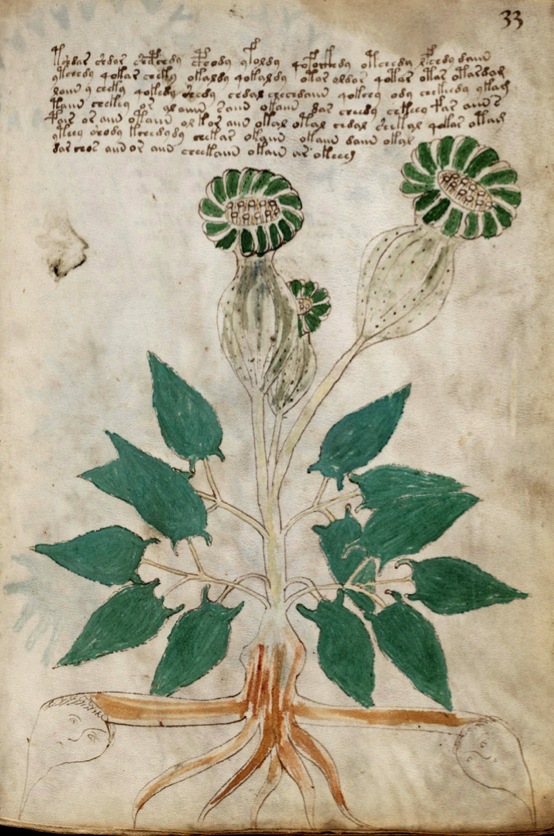

VMS Plant 33r

Plant 33r inhabits most of the space on the folio except for seven lines of text.

Plant 33r inhabits most of the space on the folio except for seven lines of text.

Seed Heads

The plant is topped with slightly rotating rosettes on swollen seed capsules (I might be wrong, but I don’t think they are flowers). There are slight vertical striations in the capsules and dots that might be an indication of texture or shadow. One of the capsules is sightly obscured behind another.

The top of the capsules have been painted in alternating green against the color of the vellum, and the lower portion is lightly washed with a bluish-gray, a color not often seen in the VMS (might it mean that these are dried before use?).

Leaves

The hastate leaves are close to the base and spread around the stem somewhat. They have smooth margins and are painted a fairly solid medium-dark green. Hastate leaves are similar to arrowheads. If the points are exaggerated, then it’s also possible the leaves are sagittate, so I tried to keep both of these shapes in mind when thinking about IDs.

Stems

The stems are moderately sturdy, painted with a very pale wash. They get thinner and branch toward the leaves. A couple of the bottom ones are slightly arched downwards. I wonder if this is an attempt to suggest a rosette of leaves around the stem.

Roots

The roots have a thickened portion in the middle, medium-thick tendrils reaching down and out, and two even-thicker tendrils or rhizomes spreading to the sides and terminating in two heads that look to me like tonsured monks. Hair styles were long in the Middle Ages, so it’s hard to imagine these heads as anything other than monks unless, of course they represent something non-human, like personified moons. If they are moons, they might stand for the name of the plant or the best time to harvest it (during the full moon?). Or maybe the moon is the governing celestial body for the plant. The tendrils are roughly painted a medium brown (not nearly as carefully as the leaves).

Prior IDs

I didn’t look up Prior IDs for this plant because I can only think of two reasonable possibilities and even the second one seems to be a bit of a stretch. Plus, I tend to disagree with existing IDs, so sometimes I’m not motivated to look them up.

Identifying 33r

When I first saw 33r, back in 2007, I noticed the exaggerated seed capsules and immediately thought of poppy. But then I looked at the leaves and roots and changed my mind.

Poppies have very jaggy leaves, and they are not hastate or sagittate. Even the Himalayan poppies don’t have leaves like plant 33r.

If the roots are rhizomes, that doesn’t match poppy either.

On closer inspection, I had doubts about the seed capsules as well.

These weren’t poppy capsules, they were water lily capsules. Probably not Nelumbo species, which have very broad capsules with large seeds that protrude, and very round leaves, but the other species of water lilies, like Nuphar and Nymphea.

Nuphar has distinctly vase-shaped capsules with striations, depressions in the middle of the upper rosette, and leaves that are heart-shaped or sagittate, sometimes like long-arrowheads.

Nuphar grows worldwide, with one of the more common species (Nuphar lutea) having a broad distribution around the Mediterranean and Eurasia. Nuphar has rhizomes (side-growing roots) that stretch to several meters, and the leaves fan out at intervals along the rhizome. I don’t know if Nuphar can have multiple flowers on one stalk, I don’t think I’ve seen that, but the other characteristics of the plant match quite well.

The Problems with Papaver

In contrast to Nuphar and the VMS, poppy plants have a very jagged leaf margin (sometimes clasping), and most of them are frondy, like ferns, not at all like the VMS drawing. The roots are finer, lighter, and usually more vertical than the VMS drawing.

Papaver seedheads are mostly shaped like covered urns, rather than vases, and the number of striations on top is usually less than the VMS, sometimes as few as five. They do not have the depression in the center characteristic of Nuphar and Nymphaea. Many poppy plants have a knob under the capsule, and sometimes a row of holes under the rosette to disperse the seeds when the wind blows. The VMS does not include these details.

Nuphar capsules sometimes have a very slight hint of a spiral overlap in the upper rosette (it’s subtle and it’s not present in all of them). I’ve never seen this in a poppy capsule although they do sometimes have a scalloped edge.

Poppy plants have tap roots, sometimes very thin tap roots, and they are often very light in color. A few species have tendrils, like buttercup roots, but they’re not usually thick as thick as the VMS roots.

What about the Bumps on Top?

One detail that had me wondering was the little bumps on the seed capsule. They’re completely unlike Papaver, but they’re not entirely like Nuphar or Nymphaea, which have a depression in the center. Then I remembered another VMS plant in which the seeds inside a pod had been exaggerated, so I wondered if this was the same idea.

One detail that had me wondering was the little bumps on the seed capsule. They’re completely unlike Papaver, but they’re not entirely like Nuphar or Nymphaea, which have a depression in the center. Then I remembered another VMS plant in which the seeds inside a pod had been exaggerated, so I wondered if this was the same idea.

Nuphar and Nymphaea have very different internal structures to the seed capsules than poppies.

- Poppy is a land plant. The seeds roll around freely inside the capsule chambers and are dispersed by wind when the capsule dries, or they drop off and get stepped on or fall out through the holes near the top, under the edge of the rosette.

- Nuphar and Nymphaea are aquatic plants and the seeds are imbedded in a spongy matrix, rather than rolling around freely. This means if you cut across the top, you will see regular rows of seeds within a lighter medium. As the capsule ripens, it is exposed to water, which erodes it, gradually releasing the seeds (some of them ripen under water). Water lilies aren’t as wind-dependent as the Papavers.

I don’t know if this explains the bumps on the top, I’ll continue to think about it, but it’s one possibility.

And now to the most interesting part…

The Root Heads

I have difficulty explaining the heads if this is Papaver. Why two of them? Most poppies have tap roots, so why wasn’t it drawn with one head and a long narrow root? Why do the thickest roots stretch to the sides? Are they meant to suggest rhizomes that propagate like long snakes under ground or water? If so, they are more similar to water lilies.

I have difficulty explaining the heads if this is Papaver. Why two of them? Most poppies have tap roots, so why wasn’t it drawn with one head and a long narrow root? Why do the thickest roots stretch to the sides? Are they meant to suggest rhizomes that propagate like long snakes under ground or water? If so, they are more similar to water lilies.

Are these monks, as per my original impulse. Or are they moons? What are the pointy parts—are they water droplets with faces? Could this indicate an aquatic plant?

Depending on which source you consult, the moon is said to be the ruling body for both poppies and water lilies. A water lily picked on the full moon was used in spells to attract a lover, but this is in recent writings, and I haven’t been able to confirm if this accurately reflects a medieval spell.

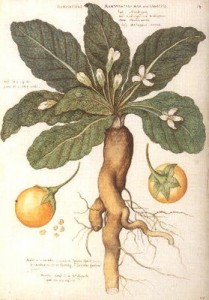

Maybe the roots have some other meaning. Various parts of water lilies are eaten, and some have sedative or narcotic effects. Monks and nuns used them to suppress their sexual desires. When prepared as an alcohol tincture, they were an-aphrodisiacs. Could this account for the heads with shorn tresses? Are they tonsured monks?

Summary

Plant 33r is not a perfect match for water lilies. It’s close, much closer than Papaver, but why would the points on the leaves be exaggerated, and why are there bumps in the tops? Is it a really bad drawing of poppy?

Are there other explanations for the heads besides monks or moons or water droplets? I’m still mulling this over, but for now, the best ID I have is one of the Nuphars or Nymphaeas, both of which are widespread and well-known in the Middle Ages.

J.K. Petersen

© Copyright 2013 J.K. Petersen, All Rights Reserved

Postscript 12 May 2019:

To make the similarities and differences between these plants more clear, I created a chart with a few samples (click to see it full-sized):