http://iccpaix.org/author/iccp-aix The Strange Formulas in the Voynich Manuscript Partially Revealed

I recently experienced the thrill of discovery—information to confirm a hunch, and new information that might pull back the Voynich curtain just a crack.

I discussed the last page of the Voynich in previous blog entries from 2013, where I speculated that it might be a charm. All I had to go on at the time was a hunch, based on its formulaic nature.

I have since discovered examples of charms that reveal something about the content and format of a charm that strengthens the identification of the VM last page.

German Charms and Healing Prayers

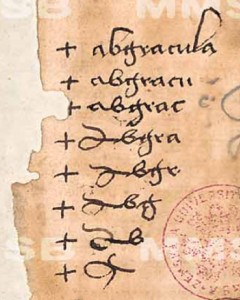

My introduction to charms happened by accident prior to posting the example on the left in 2013. I discovered this charm on the fly leaf of Der Neusohler Cato. I didn’t know it was a charm at the time, it just felt that way to me… and it really caught my attention due to its similarities to oladabad and other cryptic text written on the last page of the Voynich manuscript (it might help to refer to that page before reading this one).

My introduction to charms happened by accident prior to posting the example on the left in 2013. I discovered this charm on the fly leaf of Der Neusohler Cato. I didn’t know it was a charm at the time, it just felt that way to me… and it really caught my attention due to its similarities to oladabad and other cryptic text written on the last page of the Voynich manuscript (it might help to refer to that page before reading this one).

After discovering the Cato fragment, I searched the Web extensively for other variations of the word abracula or abgracula and found none. Two months later I tried again without success. And then I basically forgot about it.

After discovering the Cato fragment, I searched the Web extensively for other variations of the word abracula or abgracula and found none. Two months later I tried again without success. And then I basically forgot about it.

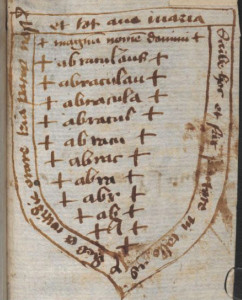

A couple of years later, in 2015, I discovered the shield-shaped charm shown to the right and noticed immediately that the Cato charm uses the same “abgracula” or “abracula” or “abraculauß” (variations are common) as the shield charm.

The shield charm was revealing because there was information included around the edges of the shield, in a mixture of old Germanic and Latin, that were not included in the Cato fragment and… the blend of languages is similar to the Voynich manuscript. This shield charm, and a couple of others that I’ll illustrate below, gave me an exciting clue as to the nature of the text at the top and bottom of Folio 116v.

Abgracula/Abraculauß/Aburacula/Abraculuß

From looking at examples, I discovered that abracula, possibly derived from Abraxas, is a very specific charm word for the reduction of fever, one that was used in Germany in the 15th and 16th centuries (I don’t yet know if it was passed down through oral or written history prior to the 1400s but will continue to watch for examples).

I also discovered there’s a formula for presenting the charms.

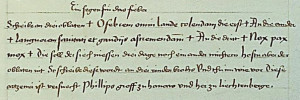

To clarify this, I’m including two manuscript clips from the same document from the Heidelberg region dating to the second quarter of the 16th century.

Note the same basic charm word (or “chant”) Abraculuß and the way it is broken down with cross symbols between each of the letter groups. Thus, it gradually becomes Abracan (quite similar to Abracadabra), Abracu, and finally Abra followed by several crosses and additional text in German. This may be a short form of the full charm.

A few pages earlier was a more extensive description of the same concept:

There is German text on the first line to introduce the purpose of the charm, then the charm word Aburacula successively broken down (with crosses in between, possibly to indicate signing the cross) and then some more explanatory information in German about how to apply the charm.

Note that both these reductionist charms are for fever (loosely spelled “fieber” and “fiber”).

The lengthier example instructs the user to write down the words and then, it’s difficult to make out all of it, but if “hencken” is old German or Yiddish for hängen, then it says to hang it around one’s neck for nine? days, along with some further instructions.

Why is this significant?

Look at the format.. first there is a description of what the charm is for, then the charm itself, then instructions for anything else that needs to be done with the charm (such as writing it down and wearing it for certain number of days).

Now look at the final page of the Voynich manuscript. At the top is something that looks like pox leben or pox leber. Pox isn’t really German (pocken is more usual), but this is old German which sometimes has influences from other languages and perhaps “pox” refers to small pox or chicken pox and leben or leber could mean “life” or “liver” as I mentioned in my previous post from 2013. If so, then it may indicate, in some way, what this charm is for treatment of the pox or the liver, for example.

So, if this is a charm in the traditional German style, the text at the top describes the malady for which the charm is useful, then the charm follows and then there are further instructions on how to apply it.

Charm Varieties

Does this mean the VM text is a charm? It’s possible, not all charms were reductionist charms, some used words or abbreviations, names of saints or bits of prayer. Here’s an example of a non-reductionist charm that is closer to the Latin-like format of the VM text:

Note the words at the end of the second line + Nox pax mox + (nox is night and pax is peace). They are reminiscent of the VM six + inarix + morix + vix +.(six and vix have meaning in Latin, the other two I don’t know).

Note the words at the end of the second line + Nox pax mox + (nox is night and pax is peace). They are reminiscent of the VM six + inarix + morix + vix +.(six and vix have meaning in Latin, the other two I don’t know).

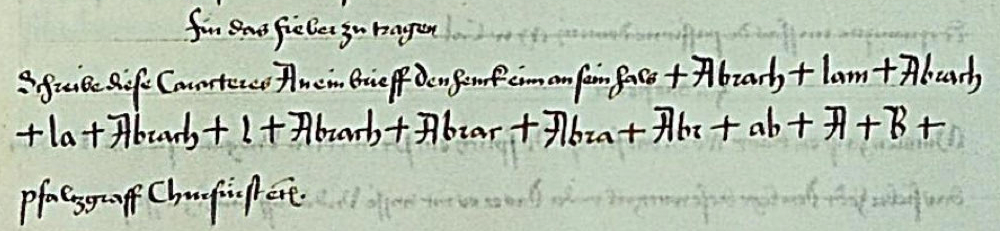

Here’s one for fever that is entirely charm words within the crosses (basically nonsense syllables):

Aglamandis was also used as a charm word (or chant) in the same document.

Aglamandis was also used as a charm word (or chant) in the same document.

Discovering these charms helped me understand the Cato fragment better. There is some torn-away text underneath the Abgracula charm that says that the charm is for fever and should be worn for thirteen days. I didn’t know this text related to the Abgracula text until I knew more about charms.

Even with all these tantalizing clues, I don’t know for certain if the text on the VM last page is a charm, but more and more it appears that it might be. It’s also possible that something else is encoded in the general form of a charm, a subtext hidden within the larger context.

What I can say is that the format and content of the text follows that of medical charms from the same approximate time period and region as Sagittarius with legs (in the zodiac section)—thus adding some circumstantial evidence that might help unravel the as-yet-unknown early provenance of the Voynich manuscript.

J.K. Petersen

© Copyright Jan 2016 J.K. Petersen, All Rights Reserved

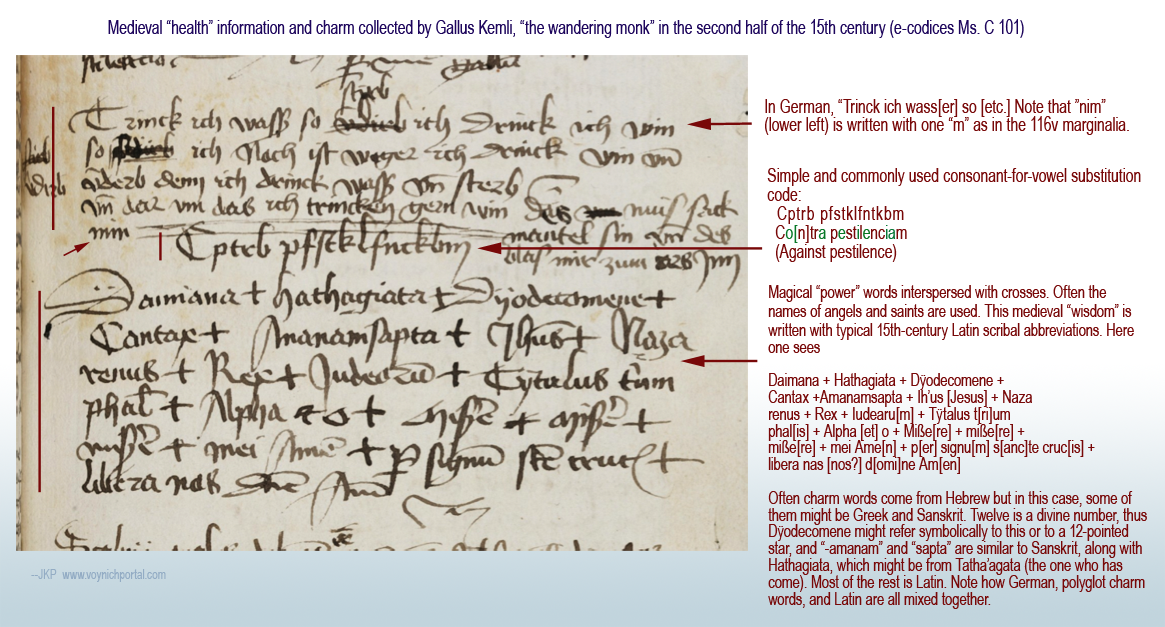

Postscript June 2018: This example may also be of interest. The wandering monk, Gallus Kemli collected a number of astrology and health-related items and this one includes a mixture of languages, and power words with crosses between them. The text is written with typical Latin abbreviations (I have expanded them to make them easier to read).

One thing that stands out for Voynich researchers is the use of a common cipher to write the purpose of the charm (against pestilence) in which consonants are substituted for vowels. This form of simple substitution code is very easy to read as is shown in the image below:

My original posts of more simple charms (a word repeated and reduced), are at this link (2013) and at this link (2015).