The upper-left rotum in the VMS “map” is often called a “volcano”—a handy term that most people intuitively comprehend even if we don’t know what the drawing represents.

Volcanic eruptions have long been memorialized in drawings and chronicles, including a Pseudo-Dionysius description from the 6th century:

Such was the violent and harsh disaster, which was sent from heaven, that fire alight and consumed those who had escaped from the terrible vehemence of the cataclysm of the earthquake and the collapse: the sparks flew and set fire to everything on which they settled. The earth itself from below, from within the soil, surged, seethed and burned everything which was there. Thus the foundations as well, together with all the storeys above them, were lifted up, heaved up and down and burst apart, collapsed, fell and burned with fire… In the end no house or church or building of any kind remained, not even the garden fences, which had not been torn asunder or damaged, or had not disintegrated and fallen. The rest burned, crumbled away and became like an extended putrefaction.

It’s possible volcanic eruptions were depicted in ancient cave paintings, but this particular cataclysm was not especially common in medieval art, which makes it difficult to identify illustrative traditions.

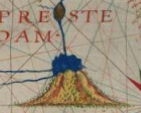

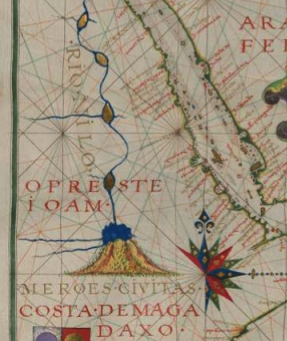

This clip is from a 1580 Portolan map (BSB Cod.icon.137) and might look like a volcano at first glance…

but it actually represents the source of the Nile River:

which I thought was interesting because there is speculation about whether the wavy shapes inside the VMS “volcano” might represent flames, water, or something else.

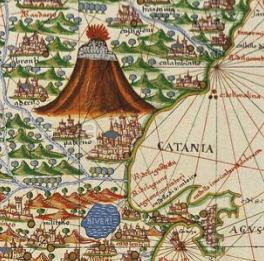

This clip from 1587 is drawn in a similar way (except that the poof is red instead of blue) and represents a volcano in Sicily (in fact volcanic eruptions changed the coastline so dramatically, it’s hard to know what it looked like in the Middle Ages):

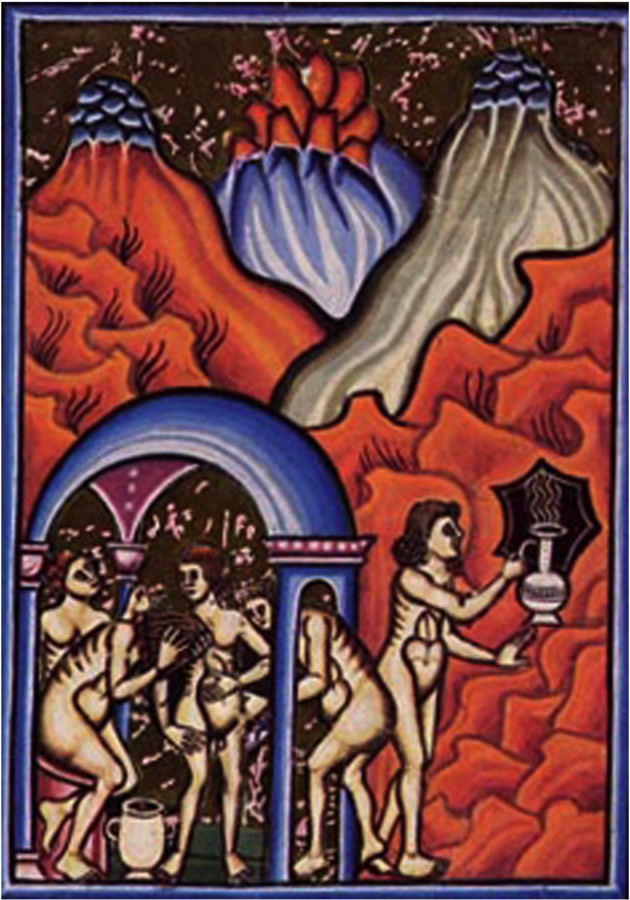

In one version of De Balneis by Petrus de Ebulo (BNF Latin 8161), bathers enjoy the healing waters at the base of a volcano:

(Note the scalloped pattern around the rim of the archway.)

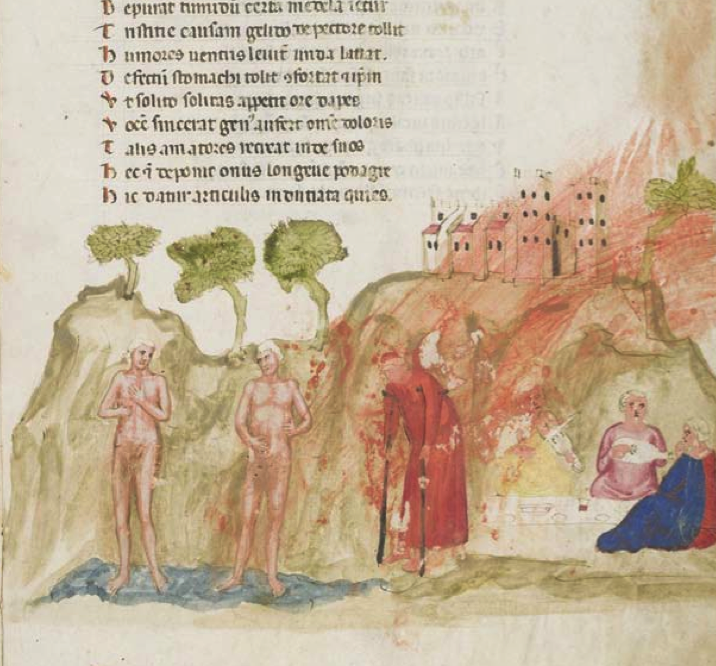

In another version of De Balneis (Angelica) the volcanic activity is more explicit:

In yet another version of De Balneis (Edinburgh), the fumes are rising on the far right, and radiating as heat (and possibly also as fumes) toward the bathers:

There is a more detailed history of the baths here (which were eventually destroyed by volcanic eruptions):

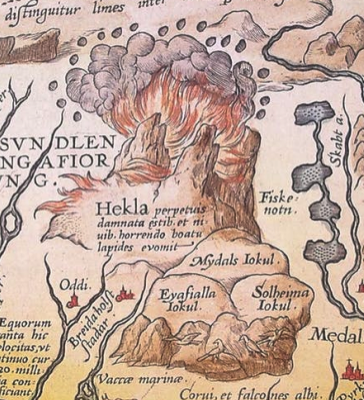

By 1585, depictions of volcanic eruptions were more naturalistic, as in Ortelius’s map of Mt. Hekla erupting in Iceland:

One of the significant thermal sources at Pozzuoli was known as The Solfatar, which was commemorated in a fresco in Rome in the early 1600s:

Baratta and Perrey (1680) recorded volcanic activity in Naples in the following engraving, at the site of the former Pozzuoli baths and the island of Nisida.

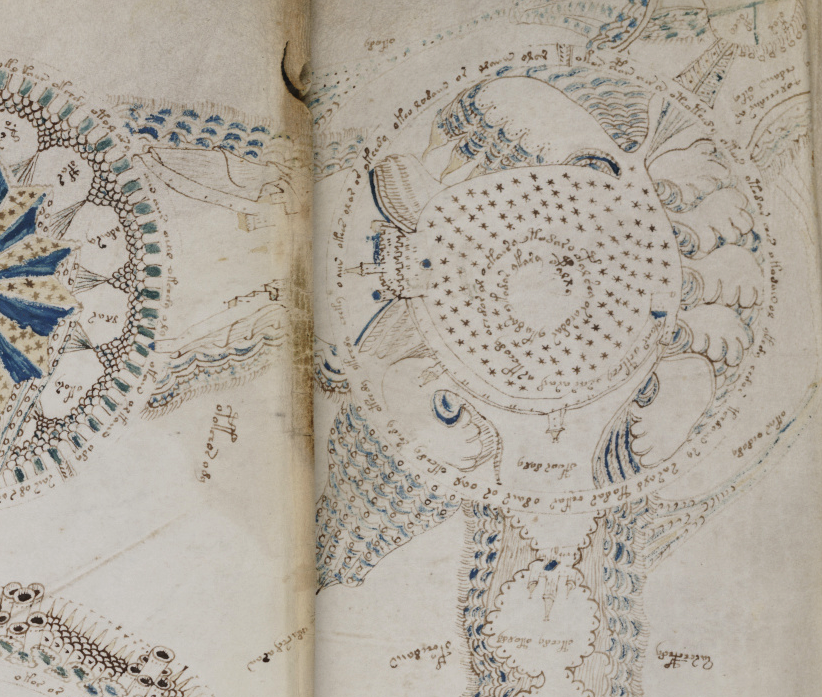

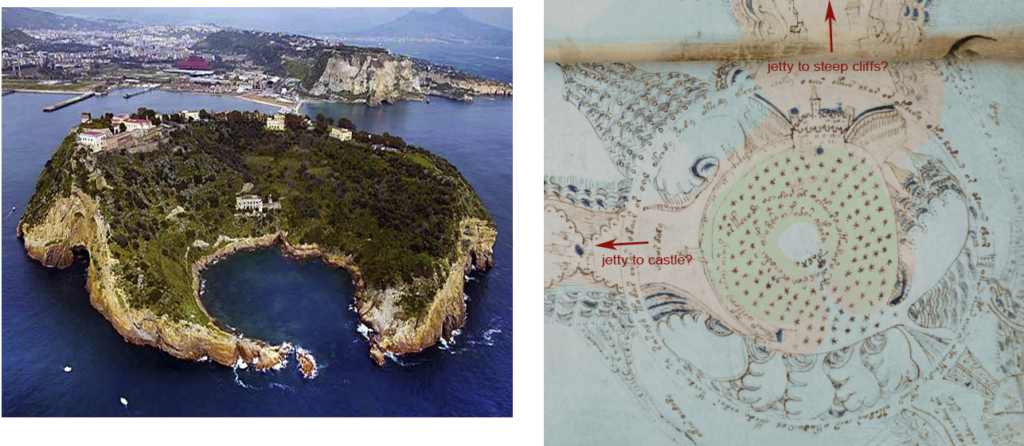

In the past, I have suggested Nisida as a possible source for the top-right VMS rotum. I have numerous ideas for this rotum, but the island of Nisida is on my Top-5 list because it matches several of the topological features of the VMS “map”.

Nisida is shaped like a horseshoe, with a “bowl” of seawater facing deeper water, and may have been connected to the mainland by a stone jetty as it is today. Sea levels were lower in the early Middle Ages and apparently rose again a couple of centuries before the eruption of Monte Nuovo in 1538.

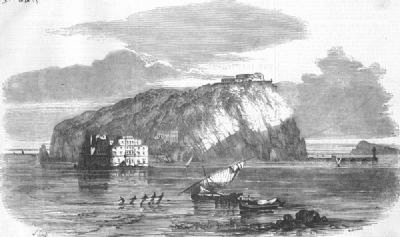

Here is a 1776 view of the Nisida crater, which formed a small harbor:

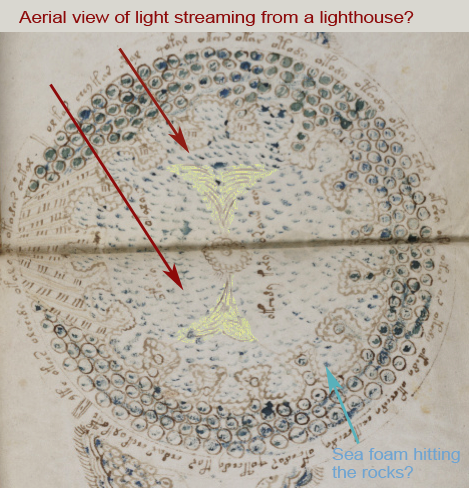

Note in the Baratta/Perrey engraving that there might be a lighthouse on one or more of the outcroppings. Could Rotum6 be an aerial view of a lighthouse with light streaming out from a central column and sea foam lapping against the rocks at the base?:

A 19th-century engraving shows a partly-submerged castle in shallow water near Nisida (perhaps connected to the island by a jetty?). There are also grottoes in the area (the VMS has a number of grotto-like images):

Below is a contemporary view of Nisida from the mainland, showing the white-stone jetty. Note the vantage point for the photo is quite high (there are escarpments in the VMS drawing between Rotum 2 and 3 that might correspond to cliffs).

It is a volcanically active area with many hilly craters and thermal vents. The horseshoe part of Nisida juts out to sea and is battered by rougher water when it’s stormy. There are castle ruins and traces of an old wall in the aerial photos.

Could the “channels” between the rota be jetties? Erosion and several changes in sea levels have probably increased the size of the hole in the center, but I don’t know how much this has changed since the 15th century.

Other Possibilities

I have much more information on a possible connection to Naples, but what if it’s not a volcano? With the VMS, there are always other possibilities…

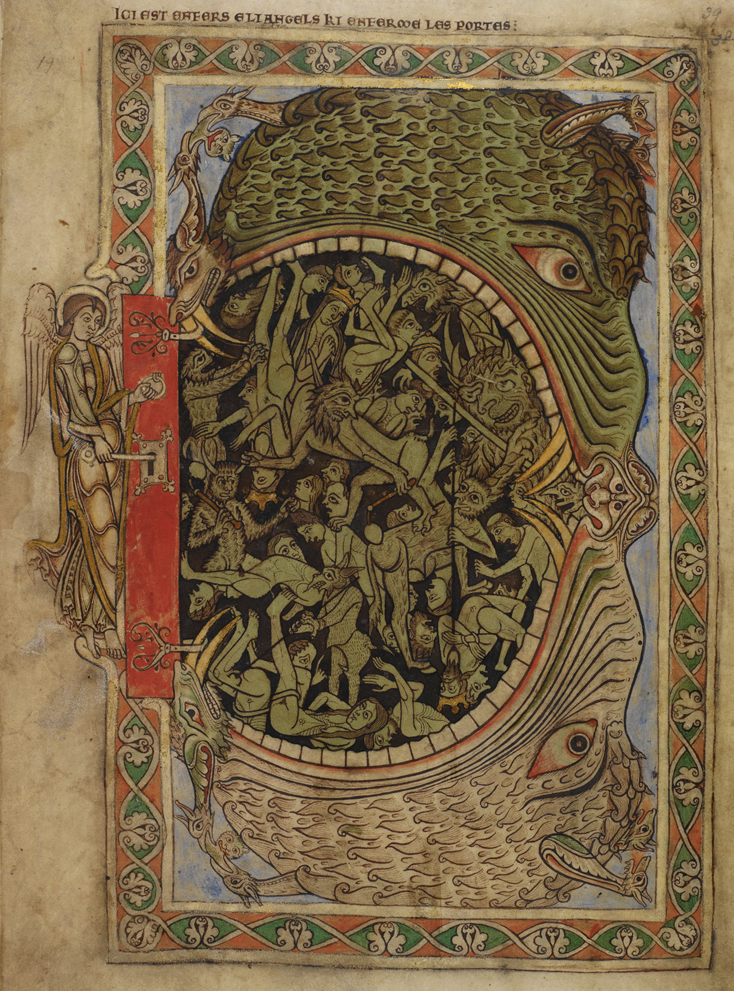

As I’ve written previously, the “volcano” in the VMS could be interpreted in many ways—as a volcano, or the biblical Mount of Olives, a coliseum flooded for water sports (which apparently were quite popular), a famous hill (e.g., the hills of Rome), a hell mouth (I think I heard the hellmouth idea from Ellie Velinska), the New Jerusalem (or some other metaphorical location or description of elemental order), the real Jerusalem, the Baths of Pozzuoli (Campi Flegrei or the sulphur craters), and a few others.

Usually a hellmouth was drawn as a dragon, whale, or crocodile with a toothy, gaping maw, as in this example from the Winchester Psalter (c. 1150):

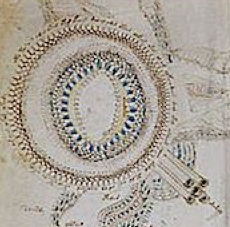

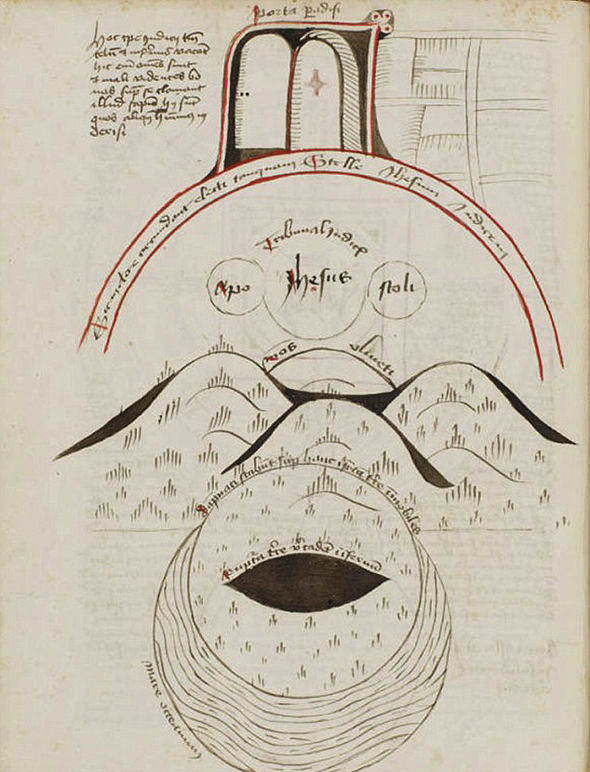

but not always. Here is a schematic representation from the Huntington Library (Germany, c. 1487) that is reminiscent of the eye-shaped rotum in the VMS map (there are even round protrusions on the top-right of the doorway):

Original Ideas

K. Gheuens offered a provocative parallel to the eye-specked fringe of a mollusc. This is one of my favorites, since there are VMS plants suggestive of sea life, including roots that resemble crab, jellyfish, and octopus. Even if none of the imagery turns out to be sea life, the organic shapes give the feeling the illustrator might have lived near the coast for some part of his or her life.

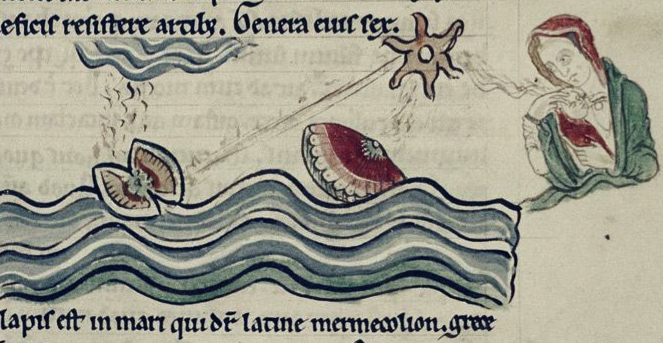

Speaking of sea creatures, this drawing in Bodley 602 has a scallop-like critter that resembles some of the “umbrellas” and other textural motifs in the VMS:

If Rotum 1 really is a volcano, then I think locations like Naples and Sicily deserve serious consideration. If not, then there are many possibilities, maybe even some that haven’t yet been suggested.

J.K. Petersen

© Copyright Jan. 2019 All Rights Reserved

Postscript Feb. 23, 2019:

I planned to post this image of Vesuvius in this blog, but I couldn’t find my link. Then I remembered I had posted it on the Voynich.ninja forum in September 2018, along with some images of volcanoes in Sicily, and other structures (like coliseums) that are large and eye-shaped. It is a re-creation published in Popular Science Monthly in 1906 of what Vesuvius may have looked like in the Middle Ages before the significant eruption of 1631:

Vesuvius was the first volcano I looked at (because the crater is eye-shaped), but I soon realized there are many craters around Napoli that might qualify as a VMS “volcano”, and there are other regions with volcanoes that somewhat match the topology in the VMS rota.

It occurred to me when I first noticed the “pipes” on the rosette foldout, that they might be Medieval or Roman aqueducts, or perhaps “soffioni” (hot steam jets) that occur naturally (or might have been installed) in some of these thermally active areas.

Steam vents sometimes had spiritual significance. Lewis R. Freeman reported in Popular Mechanics that the Romans erected an oracle (and later a spa) at the steam vents of Larderello, near Volterra, Tuscany (look up Priest Consulting Oracle in the Museo Guarnacci Volterra to see a frieze). Could the temple-like dome in the central rotum be an oracle or later spiritual center? Even after Europe was Christianized, many of the Pagan oracle locations were retained as religious sites.

The Romans also built a coliseum in Volterra and, right next to it, a bath complex. Volterra was under Florentine rule in the 15th century and now is a major geothermal engineering center.