21 February 2020

Medieval charms are like puzzles—ancient traditions, archaic names, corrupted words, blended languages, and numerous abbreviations. To decompose or interpret them, one has to learn about historic religious practices, both eastern and western, and to study hundreds of charms so that the general patterns become more evident.

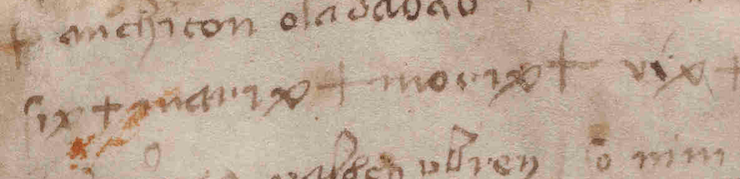

I’ve posted several blogs on charms, talismans, and amulets. It was the word oladabas on the second line and the repetition of six, morix, marix on the third line of VMS 116v that started me on this journey. These patterns reminded me of magic words (like Abracadabra) and patterns of sound-repetition that have long been associated with ancient magical rites.

The earlier blogs are here:

- Repeated sound sequences and ancient words like Abracadabra (July 2013)

- Abracula charm, talisman, and crosses (Dec. 2013)

- Talismanic and shield charms (Nov. 2015)

- Examples of medieval charms (Jan. 2016)

- Shield charm and talisman (Nov. 2016)

When I looked into this subject in more depth, I discovered that various versions of Aladabra, Abraca, Abracula, Abracadabra, ala drabra, et al, are closely related, and shortenings of the name in a repetitive line or diagram are not just to save space but to “reduce” the power of illness or malign spirits. Sometimes these are intended to be chanted aloud. Other times they are written on small squares or strips and worn on various parts of the body, or buried in the ground.

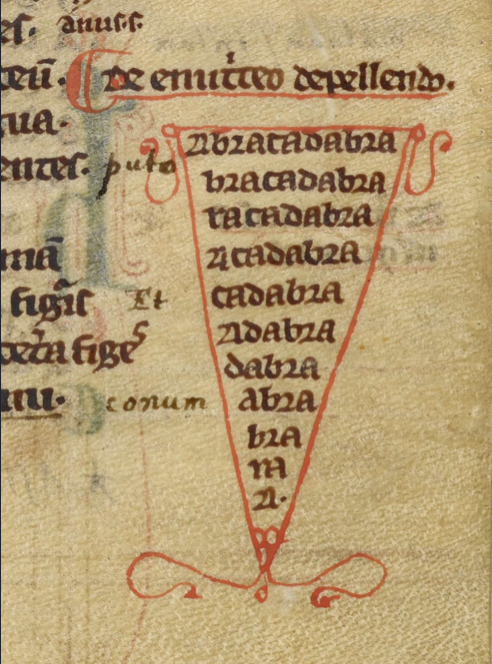

Abracadabra is possibly of Semitic origin and is mentioned in Serenus Sammonicus’s Liber Medicinalis as an incantation for fever as “chartae quod dicitur abracadabra”.

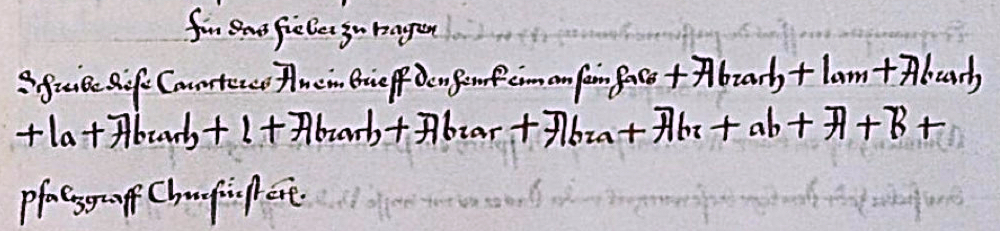

The charm words were not always written within shields or triangles, often they are within circles or pentagrams. Sometimes they are written in more prosaic style… let’s look again at an example I posted in 2016—a charm for fever:

The primary sequence begins with the word Abrachlam and is broken down in two sections Yessentuki Abrach + lam (you can think of this as alpha and omega, the beginning and end of the word). The beginning is reduced as follows:

Abrach, Abrach, Abrach, Abrach, Abrar, Abra, Abr, ab, A, B

And is interspersed with the shorter sequence from the end:

lam la l

Note how this differs from the shield charms (and from many of the more prosaic charms). This intertwining of the beginning and end is not common. Usually the ending is simply dropped to gradually reduce the word down to one or two characters, but the way the parts are interspersed in this example might be relevant to the VMS, as will be discussed farther down.

But first, a little more background. To fully appreciate charms, it helps to know a few abbreviations…

What is “aaa”?

If you saw “aaa” in a manuscript or engraved on a talisman, you might scratch your head, but the history of charms reveals the meaning of this cryptic abbreviation.

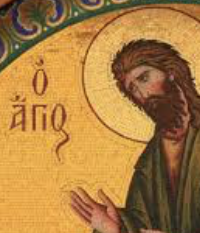

When I came across the incantation “Agios Agios Agios” in a medieval manuscript, I recognized it because it is commonly written on Greek icons with images of saints, Jesus, and God (like the Arabs, the Greeks frequently exploited the calligraphic characteristics of letter shapes and intertwined them like monograms). On the right is a typical icon labeled O Agios. Agios means “otherly” and is often translated as reverend, holy, or sacred. It is written and abbreviated in numerous ways.

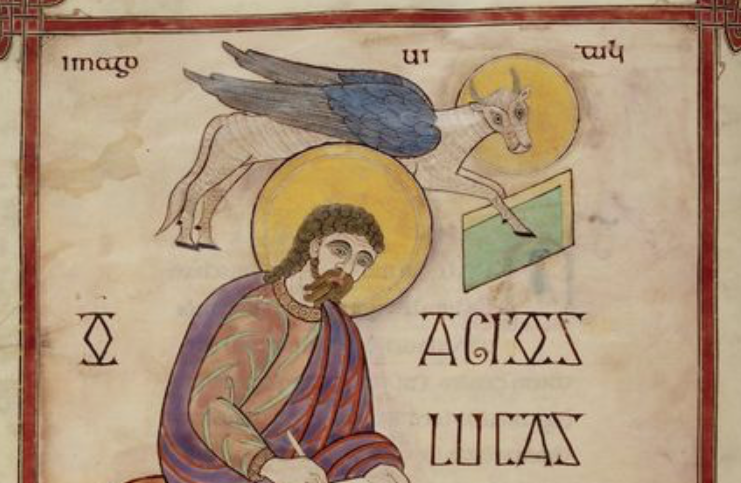

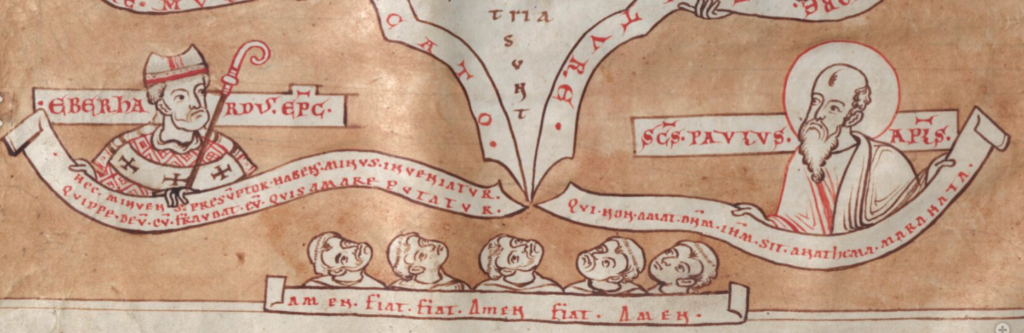

Agios was also Latinized in the Middle Ages. There are several examples in the Lindisfarne Gospels. I include one here:

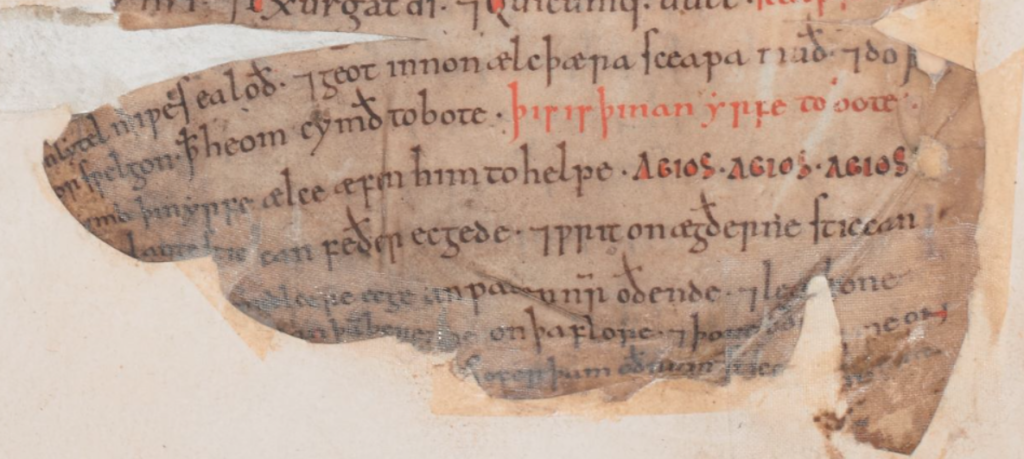

Another example of Agios, in the context of charms, is in an Old English manuscript from the 11th century. The reader is instructed to sing Agios Agios Agios to the cattle each evening (ælce æfen) as a form of protection and aid (him to helpe):

Agios is sometimes abbreviated as Ai, and the abbreviation aaa is also a shortened version of Agios, Agios, Agios. But Agios, Agios, Agios (used in priestly invocations) is itself an abbreviation. It comes from an old hymn in Greek:

Ágios ó theòs, ‘ágios ìskhuròs, ‘Ágios àthánatos èléeson èmâs…

This hymn is known as the Trisagion (thrice Agion) and is sung in liturgies and processions. If a person is familiar with the hymn, then they would recognize Agios, Agios, Agios in the context of a charm without having to see the full text of the hymn. It seems likely that it is a direct reference to the hymn because the cattle charm instructs the user to sing the charm words.

Thus, extreme abbreviation to single letters or double letters was not uncommon.

Other Mystery Abbreviations

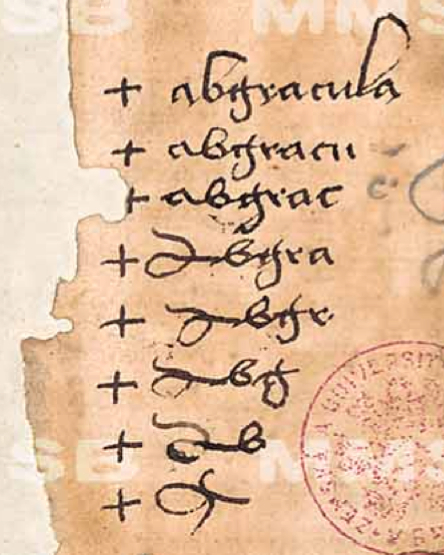

In previous blogs, I posted examples of Abracula/Abgracula (right), a word gradually reduced to a talismanic shape (sometimes as a shield diagram), and frequently combined with crosses. Since posting this in 2013, I have also seen the word shortened to “Abrac” and “Arac” in textual charms.

In addition to shortened words, medieval charms often include repetitious sounds, in addition to Hebrew and Latin,”power syllables”, names of angels, and other components.

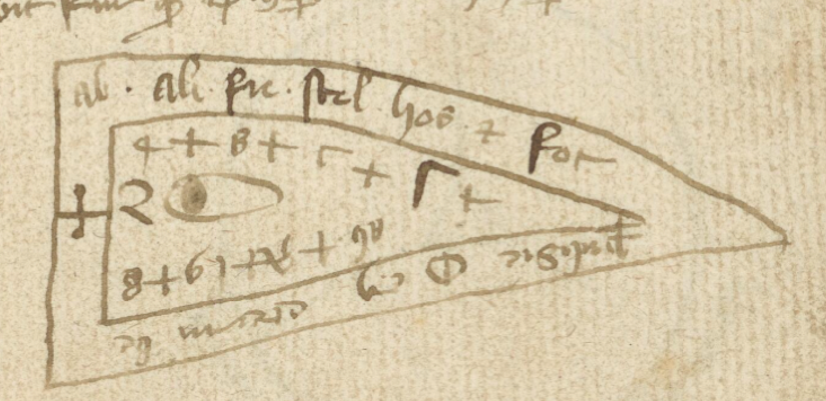

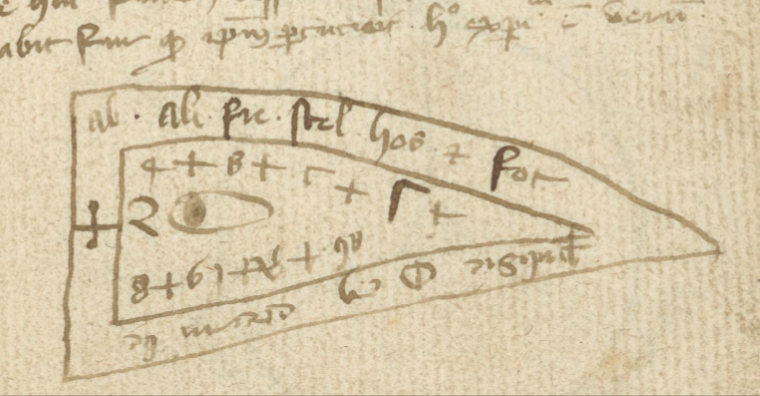

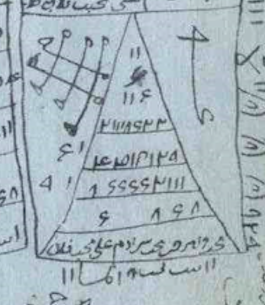

The following shield charm begins with “ab” in the upper left, followed by what appear to be mostly abbreviations in the outer band. The inner band also begins with “ab” if you flip it around, followed by numbers and a mixture of Greek and Latin letters. I was wondering why shield charms were common in Latin manuscripts and I’m not sure of the specific reason, but in Hebrew and Arabic exemplars, triangles are very common, so perhaps this is an adaptation of the triangle:

I noticed “ab” was frequently at the beginning of charm words and thought it might trace back to the biblical Abraham, but there’s another possibility… perhaps “ab-” is popular in charm words because it roughly represents the first two letters of the alphabet (Greek, Hebrew, Arabic, Latin).

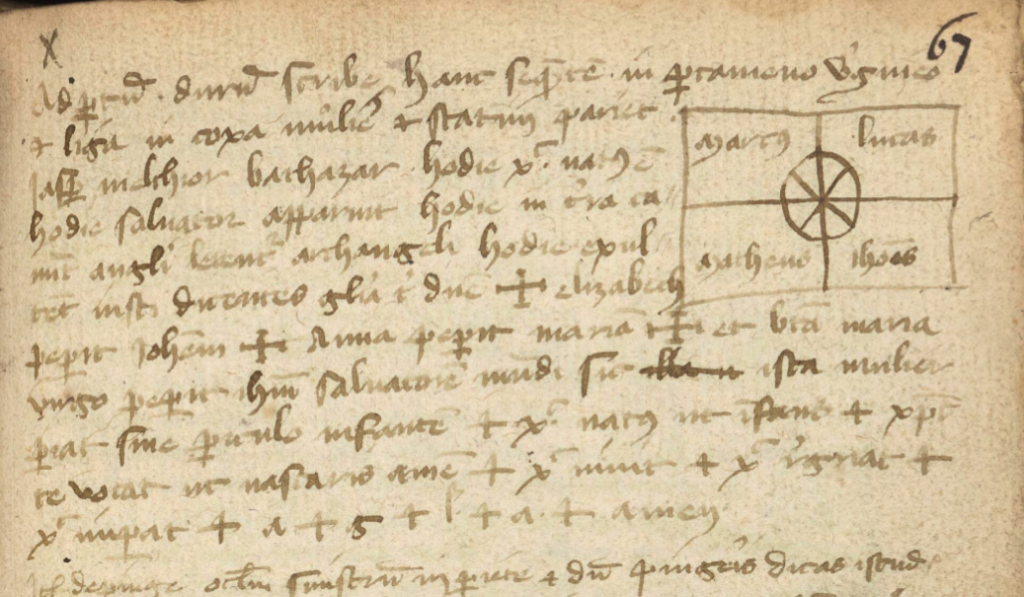

Below is another example from the same manuscript. In the top right are the names of the evangelists within quandrants, with a crossed circle in the center. On the third line are the names iasp[er] (a reference to Casper) melthior and bathazar (probably Balthazar), the three wise men, followed by invocations to archangels, followed by crosses and more names, including the following interesting passage:

+ elizabeth peperit Ioh[ann]em + Anna peperit Maria[m] + bra’ maria virgo peperit ihu’ (Jesus) Salvatore’ mu[n]di…

The names of women and their offspring are included in a number of childbearing charms and, if you scan down to the last line, you will see + a + g + l + a + amen, which is a clue that “agla” like “aaa” (Trisagion) is probably an acronym.

And so it is. It comes from the Hebrew אגלא for “Attah Gibbor Le’olam Adonai”. Adonai is one of the names of God, frequently included in charms with Eloyim and Sabaoth. This invocation acknowledges his might and power.

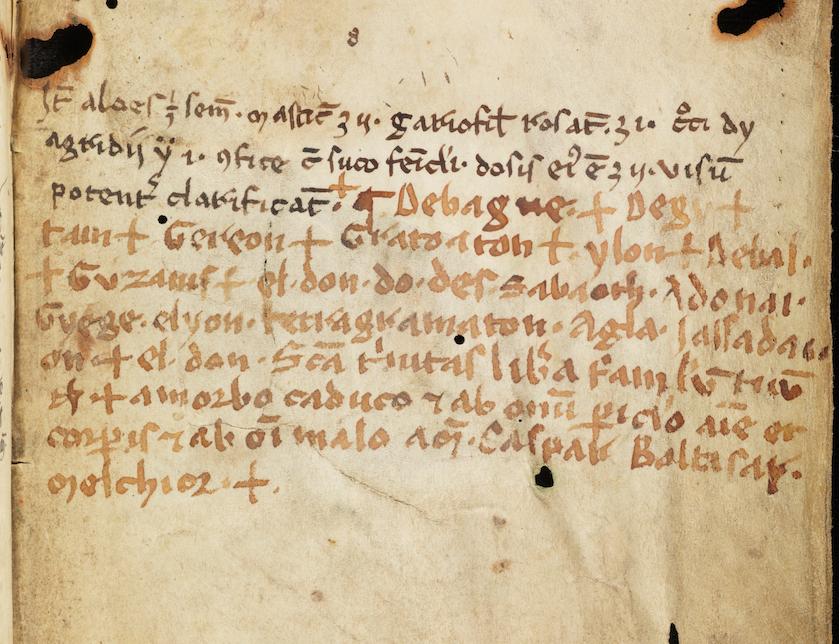

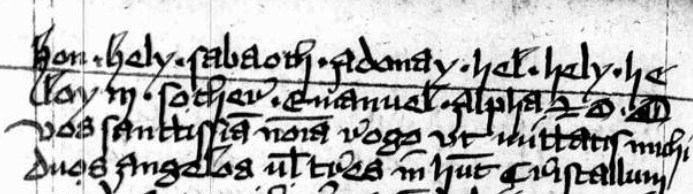

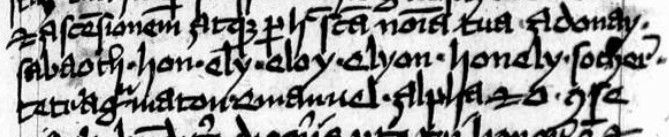

The following charm, added at the end of Arau MS Wett 4, also includes Adonai, Sabaoth, Grege, elyon, and tetragamaton (which also has Hebrew origins). At the end, are Baltasar and Melchior, as in the previous example and, as is common, several crosses (which in some cases indicates a genuflection):

Near the end of the sixth line is the now-familiar agla.

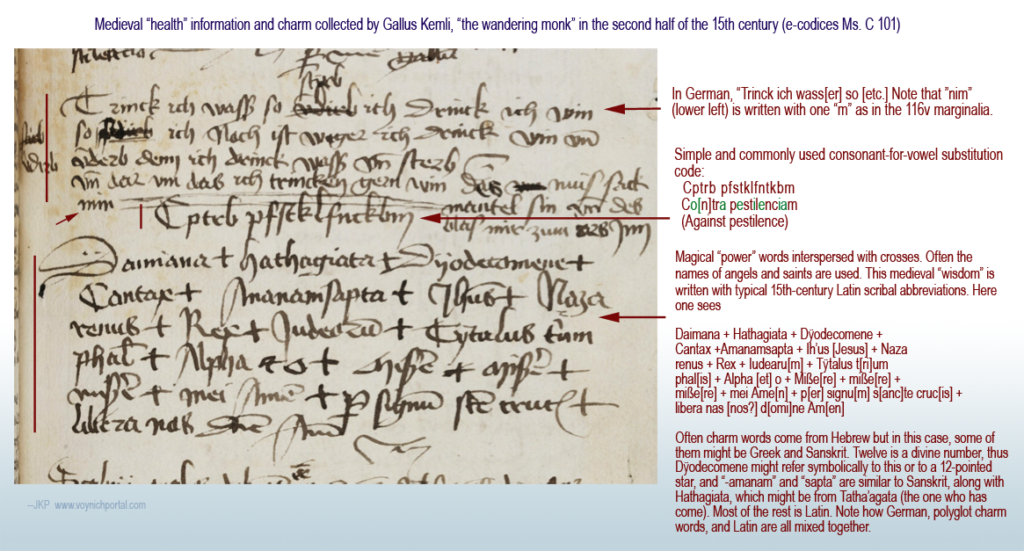

Here’s a pestilence charm with a similar format and a brief partial-substitution cipher that I posted in June 2018:

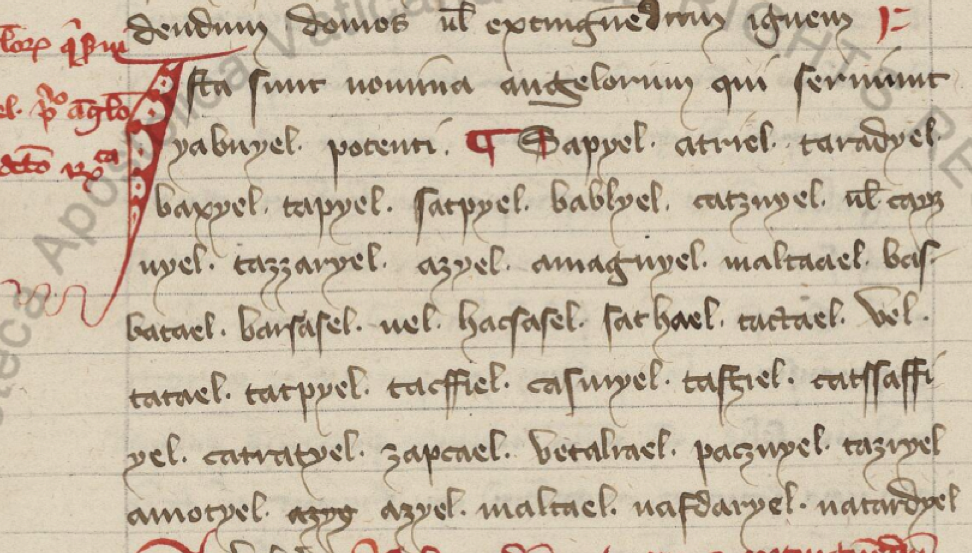

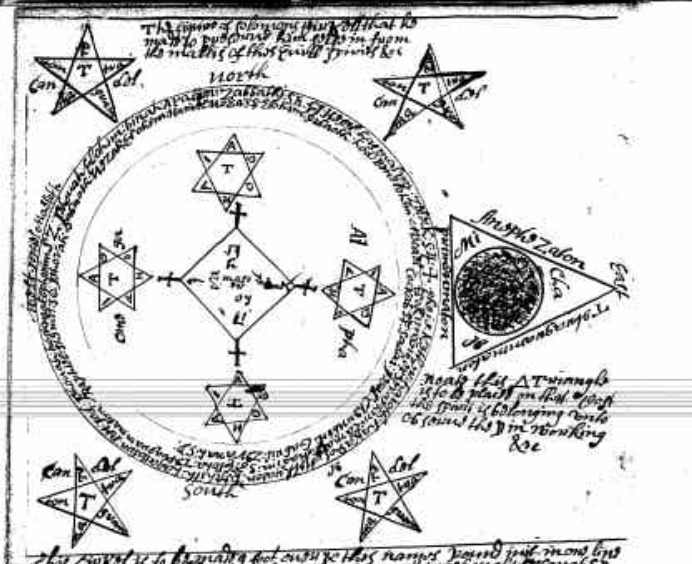

Names of angels are also very common in charms and general books of magic. Here is an example with names of angels (and other sacred personages).:

Specific angels were said to be associated with each hour of the day or night, with the archangel Michael presiding over the first hour of the day (the time when many rites were instructed to begin).

Sound Repetitions

I mentioned Agios as a repeated invocation, but there are also many vaguely Hebrew or Latin-sounding phrases that don’t appear to mean anything or which are simply repeats of names. Often the cluster of syllables is identical or self-similar.

For example Hatim, Hatim, Hatim (also written hatyn, and probably representing a name), kadosh, kadosh, kadosh (the Hebrew word for sacred) and eye, eye, eye can be found in medieval conjurations for Thursday (as described in the Heptameron and by Lauron de Lawrence, 1915) . The odd-looking eye, eye, eye found in BSB Clm 809, is an abbreviation for eschereie, eschereie, eschereie.

What might be even more interesting to Voynich researchers is sequences that are self-similar…

In a childbirth charm in MS Sloane 3160, the text following christus regnat is erex + arex + rymex. Looking more closely, if the wordplay is based on “regnat” or “rex” then eREX aREX RymEX might be the basis for the pattern.

Sometimes the short Latin-like words refer to longer statements, just as aaa refers to agios in its longer form as agios + agios + agios or as a hymn. For example, the following statement:

In nomine patris max, in nomine filii max, in nomine spiritus sancti prax.

will sometimes be abbreviated in charms as max + max + prax.

Another sound sequence found in charms is habay + habar + hebar, with habar being the Hebrew word for incantation. Note how each word varies by only one letter.

In VMS 116v, on line three, we see siX + mariX + moriX + viX + so IX is common to all four and this being the VMS, I can’t help wondering if “ix” was chosen because it also doubles as the number 9. There are some oddities of spacing… the ix in each case appears to be written in the same handwriting and the “a” is the same as others on the page, but the backleaning i character (resembling EVA-i) in “vix” is quite perplexing. Was it intentional? Or a slip into thinking in Voynichese? Or is it a later addition in another hand?

Spelling was quite variable in the Middle Ages, so I looked up “morax” as a substitute for “morix” and discovered that morax or more commonly marax is a demon, one of the fallen angels—a spirit that could be summoned by Solomon, appearing as a bull. Marax governs astronomy, herbs, and precious stones. He can be invoked at any time except twilight.

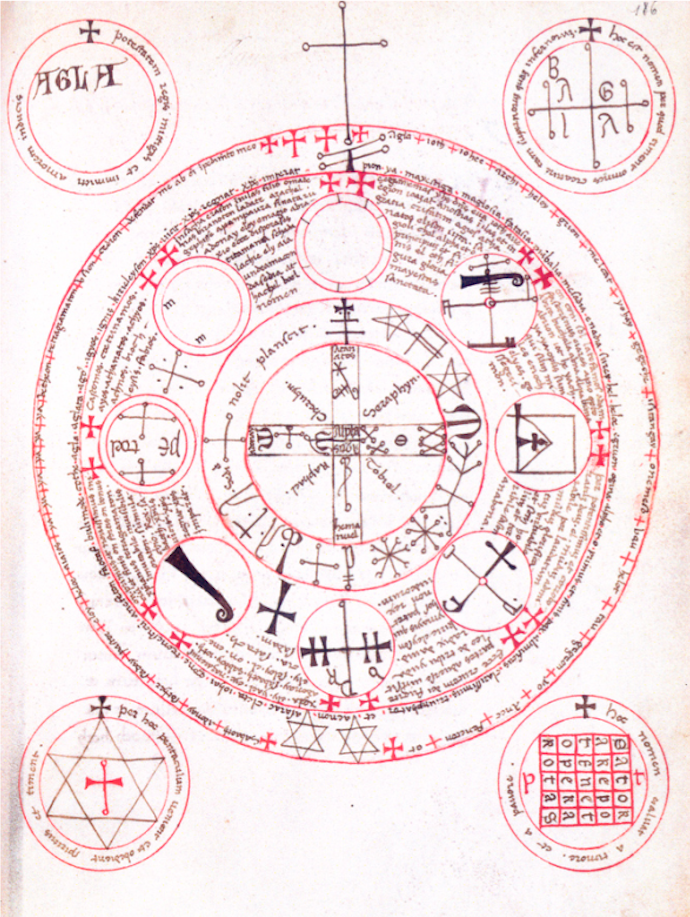

This information comes from De Laurence’s 1916 Lesser Key of Solomon, which is translated from manuscripts in the British Museum. BNF Italian 1524 is another version that includes this diagram with AGLA in the top left, and a magic square in the bottom right together with other talismanic symbols:

An earlier manuscript said to have inspired this is the Livre des Esperitz (Book of Spirits, Trinity O.8.29), a French grimoire with influences dating back at least to the 13th century (Boudet, Médiévales). The French version calls this demon “Machin”. Other variations include Mathim or Bathym. Ancient sources mention Tamiel or Temel for a demon with the same characteristics.

These fallen angels were said by some to be fallen stars. Others saw them as personifications of human failings.

Some of John Dee’s writings are referenced in an 18th-century hand-written version of the Book of Spirits that is now in the Penn State Library (Ars Artium, Ms Codex 1677). The book includes a reference to the papers of Alchemist Richard Napier and a statement on a flyleaf that “I” (the scribe) copied the book from an old manuscript written upon parchment (British Royal Commission).

The Royal Commission also mentions a book on Kabbalah “bought at Naples from the Jesuits” Colledge, &c.” and a book on alchemy that “the Government seized upon the Convent and sold their Library.” Another writer, possibly C. Rainsford, further mentions that Sepher Rasiel came into his hands from the Naples Jesuits (1874), which provides some interesting connections between the Jesuits and occult books.

But to get back to our demon…it appears that the name morax/marax, when associated with fallen angels, originated sometime in the late middle ages or Renaissance, and we cannot be sure that marix or morix in the VMS is a spelling variation, but the similarity is provocative.

Now let’s look at another way to generate charm words…

Magic Squares

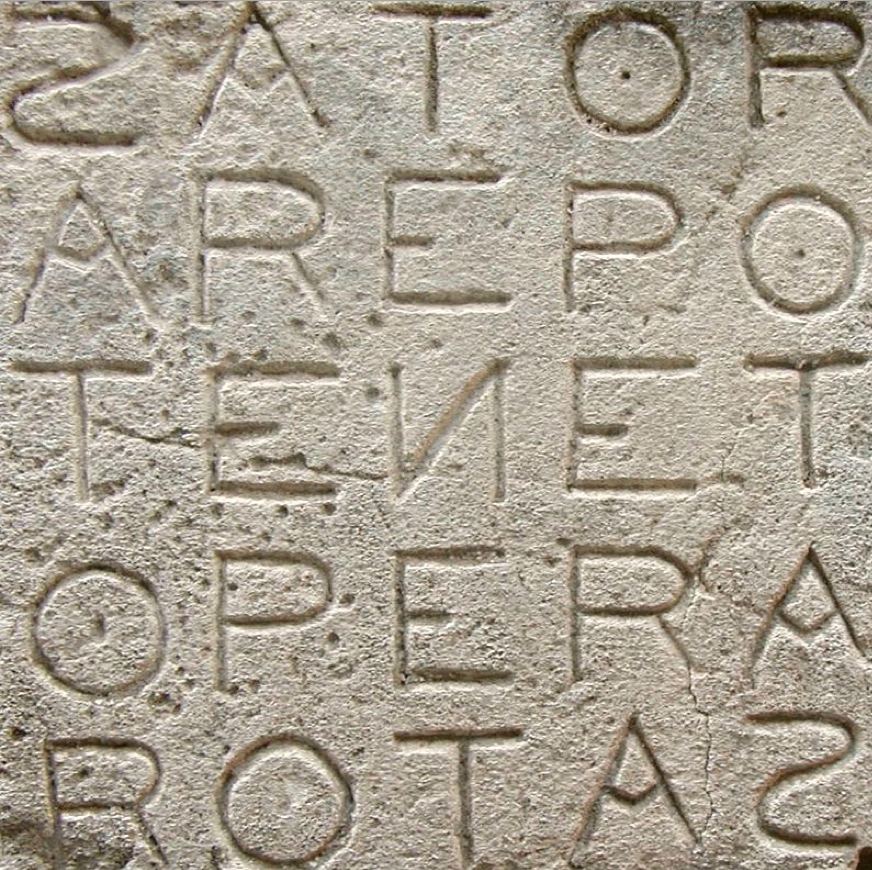

When I see self-similar patterns, I wonder if there is some formulaic way in which they are generated, other than simply having a couple of letters in common, as might be the case with palindromic magic squares. I saw one pattern that included the phrase ARAPS IASPER SCRIPT, which immediately reminded me of the famous SATOR/ROTAS square.

Many people are familiar with this square. It comes from ancient times and is frequently in books of magic, as with the Trinity example above.

Sometimes the square is omitted to show just the letters, as in the following incantation to influence friends in The Clavicle of Solomon, MS Sloane 3847. Note also the names of the three wise men, which were in MS Wett 4 pictured earlier, a variety of biblical names, and the four evangelists:

S. Sator, arepo, tenet, opera, rotas, Ioth, heth, he, vau, y. hac, Ia, Ia, Ia, papes, Ioazar, anarenetõ nomina sancta ad implete votum Amen. Baltazar, Iapher, Melchior, Abraham, Isaac, et Jacob, Sydrac, Misaac et Obednego, Marcus, Matheus, Lucas, Johannes, Ioron, Sizon, Tiris anfraton, adestote omnes in adiutorium ut a quacunque creatura voluere possim graciam impetrare.

Have you ever played with the letters in the SATOR/ROTAS square to create other words? For example, I noticed that PATER NOSTER (Our Father) can be constructed, and Pater Noster is also common in charms.

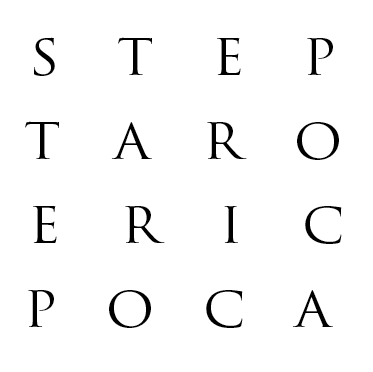

This made me wonder if charm sequences similar to ARAPS IASPER SCRIPT (ones whose origins are harder to identify) were loosely based on the SATOR idea. For example, something like this (I created this in a couple of minutes, so it’s not elegant, but it’s good enough to get the idea across).

Letters in this palindromic square can be picked out to generate the words ARAPS IASPER SCRIPT. To the medieval mind, perhaps they carry some of the “power” that comes from a palindromic square. Sound-similarity occurs almost by default when the character set is small.

Thus, I became suspicious that magic squares might have been used to generate a subset of charm words that are harder to fathom, and then I found this…

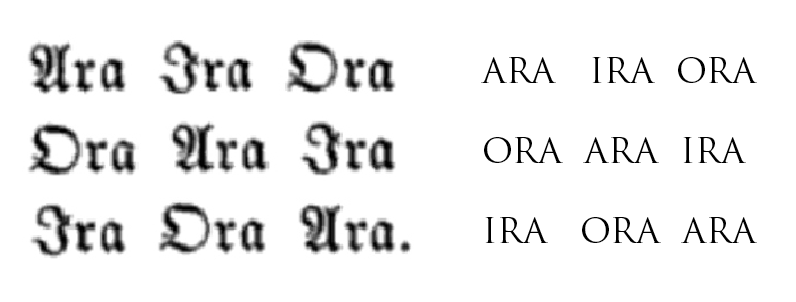

Abracula appears abbreviated as Abrac in Abrac Abeor Abere in Peter of Abano’s Heptameron. And it is apparently also the basis of “Ara”, an abbreviation used in a magic square with the following components:

Note the similarity of Ara and Ora to “aror” on folio 116v of the VMS. The preponderance of “a” and “o” (and the proximity of an “r” shape) is also a characteristic of the VMS main text.

If a string of something that looks like nonsense syllables were derived from other words in the same charm, then self-similarity across several lines would be significant. Even though the sequence SIX MARIX MORIX VIX isn’t sound-similar to the rest of 116v, it is similar to words in charms.

Practical Magic

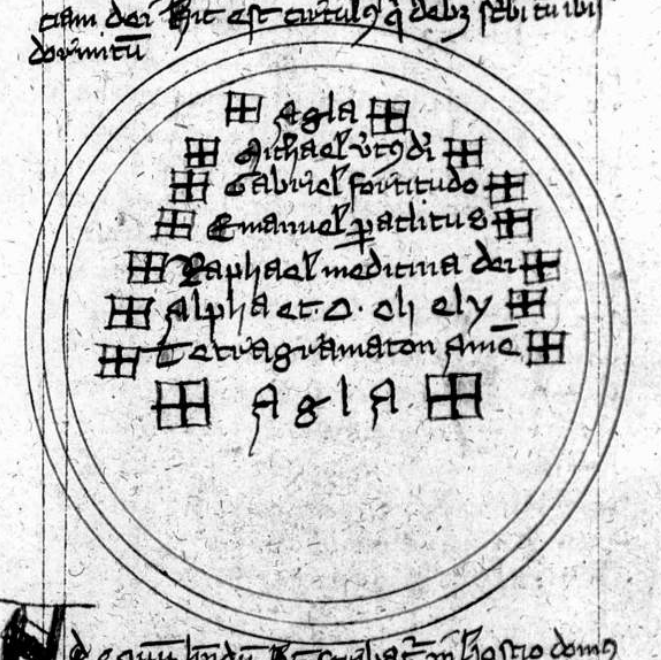

The following example incorporates sacred names and abbreviations (typically Agla, Amara, Tanta, and others) within a circular frame surrounded by boxed crosses:

If it is included, the name of God is often written first. Sometimes it is written several different ways. Other times the name of God is expressly omitted or only partially written, as certain cultures have prohibitions about writing the name of God.

AGLA is not specifically a name of God, but like max + max + prax represents a shortened phrase that includes the name Adonay, a reference to God that is very often in charms. Other common names in charms are Eloym and Sabaoth.

If you see C + M + B or G + M + B, there is a good chance it stands for Caspar Melchior Balthasar. M + G + E would be Michael, Emanual, Raphael and M + M + L + I is Mathew, Mark, Luke and Iohn (John). Names are sometimes written out in full or partly abbreviated. If there is limited space, the archangels are often chosen over other angel names. Sometimes many angel names are included.

Variations on words for friendship or love were also common in charms to win someone’s affections (or to get a girl to lift up her skirts).

As mentioned above, this shield-shaped charm symbol has numerous abbreviations and, as examples have shown, it was very common for charms and remedies to include Greek and Hebrew letters.

Unfortunately, when words or phrases are distilled down to one or two letters, it becomes harder to interpret them unless you can find a similar charm with the words written out. In this case, it’s possible the “ab” on the top-left is abracula or abracadabra as these words appear often in charms (especially shield charms):

Western charms have much in common with ancient Mediterranean, Arabic, and Indic charms, many of which have been transmitted through manuscripts created by Jewish and Greek scribes. Invocations to God from the Qur’an are sometimes included in divinatory diagrams.

Pentagrams, circles, shields, triangles, stars of David, and other geometric shapes are commonly found in both eastern and western manuscripts. Also common to eastern manuscripts is a double rectangle, with the second rectangle offset, with eight loops at the point, a symbol for Earth. Western manuscripts also include these shapes, but tend to favor circles, shields, stars, and rectangles. Sometimes the strange shapes that accompany divinatory frames are corruptions of Arabic letters and western-Arabic numerals.

Figures composed of spidery lines ending in circles are common in books of Kabbalah, and often the names of angels are expressed this way, as well. Some of the western alchemy and astrology symbols have these characteristics, as well. Shapes that resemble EVA-t are natural variations of these kinds of patterns.

Sword and Soil

In medieval books of magic, drawing a circle in the dirt with a sword or stick is a frequent instruction, and incantations may be chanted from the edge or inner portion of the circle, depending on the specific kind of charm. The user is frequently directed to face east. If animals are used in the ceremony, they are usually sacrificed (and sometimes buried in a specific spot) or let free with the understanding that bad spirits will depart with the animal. The unfortunate Hoopoe, a beautiful bird that is fast declining, was a favorite sacrificial victim.

Often a young virgin boy was used to read the signs in water, oil, or other somewhat reflective surfaces. It was assumed that someone with enough youth and innocence would tell the truth. Often the boy was asked to reveal who had perpetrated a crime and people were gullible enough to accept the boy’s interpretation and to punish the “guilty”.

This may seem irrational and superstitious, but even respected 16th-century scholars like John Dee believed it was possible to “channel” information from other realms via a scrying mirror and a medium (in this case, Edward Kelley, who was neither young nor virginal).

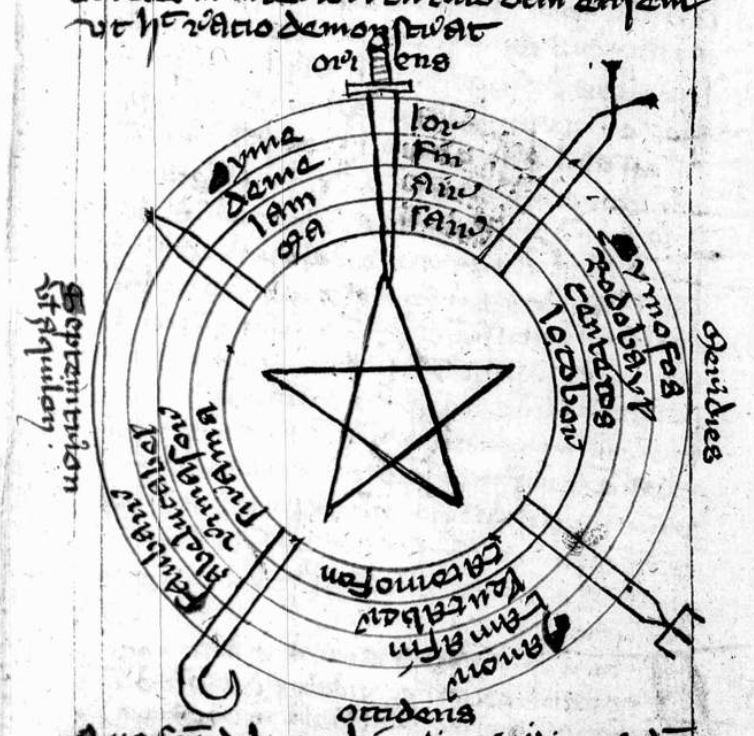

This example from a 15th-century manuscript (Clm 849) is circular, with a central star, five divisions, and a sword at the apex representing east (east was commonly shown as “up” in medieval maps and many magical diagrams). This is the general form of diagrams that were inscribed on the ground, sometimes with a real sword.

It was rare for books with diagrams like this to survive as they were actively sought out and destroyed by authorities. Sometimes just owning one of these books could get you imprisoned:

Instead of a figure, sometimes the words or letters for alpha and omega are written in the inner circle. In BL Sloane 3648, the central circle includes pentagrams with ADONAI written in each outer triangle and alpha and omega split across them on either side:

As mentioned earlier, charm words are often in groups of three with sound similarity. Sometimes the words are identical, as in Amen, Amen, Amen, or Fiat, Fiat, Fiat.

Sometimes they vary only slightly. Frequently the second and third words are only one or two letters different from the one that came before, as in Adra Adrata Adratta, or Adra Adrata Adracta, or one I see quite frequently, Hel, Hely Heloy (sometimes written Hely, Heloy, Heloe, Heloen or Helion, Heloi, Hel), or the variant shown here as Ely Eloy Elyon:

I want to emphasize this because self-similar patterns are quite frequent in the main text of the Voynich Manuscript and I don’t think auto-copying is the only possible explanation. Before I post examples, I want to cover one more thing in folio 116v…

Names in Charms

In classical charms, a reference or invocation to Pagan heroes or gods was common. After Christianity became prevalent, the format remained essentially the same, but Hebrew and Christian names for God, angels, and the virgin Mary were often substituted, or shared space with older names whose origins were no longer known.

The second line of 116v has a word that might be “cere” which might be a Pagan reference to Ceres the goddess of crops and fertility, but there’s not enough information to know.

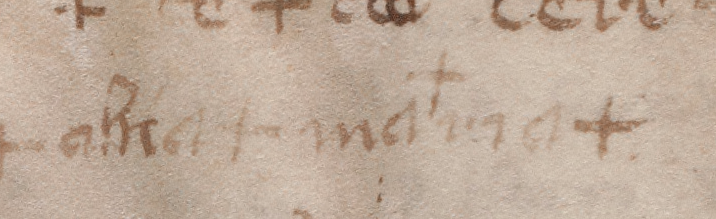

The next line includes the word maria with crosses on either side (which I mentioned in 2013 might be the sign for genuflection), and there is one that looks like it was inserted as an afterthought between the a and the r. This is quite possibly an invocation to the virgin Mary:

The word before “maria” is harder to discern. It looks like ahia, but the “i” is oddly written and the last stroke of the h is oddly abrupt and slightly truncated. It’s almost like an h badly melded with a k. It’s not quite a “b” (there is no bottom cross-stroke).

But let’s investigate the plausibility of ahia. This could be a reference to the prophet Ahia in the Biblical Book of Kings, who is best known for his prophesy that Jeroboam would be king. If the text on 116v is a medical charm, then Ahijah/Ahia/Ahiya would be an appropriate name, as Ahia the Shilonite was called upon in the Bible to be an intermediary between mortals and God in much the same way as Mary is asked to intercede on behalf of mortals in distress.

How Does This Relate to the VMS?

Patterns of repetition, in which subsequent tokens are only slightly different from preceding ones, are very prevalent in the VMS, but most of them are sequences of two (these can be found throughout the manuscript).

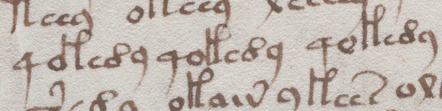

There are also dual and triple repeats with no apparent changes:

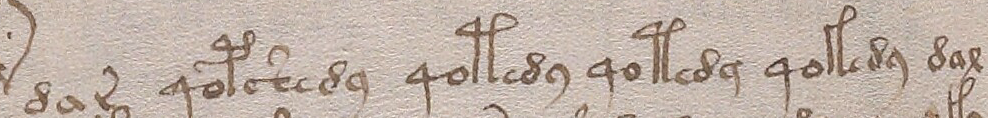

Are there sequences of three where the variation is limited to one character each time? A further example from folio 79r comes close, except that the third repetition has two changes, thus qolkeey qolkeedy qokedy:

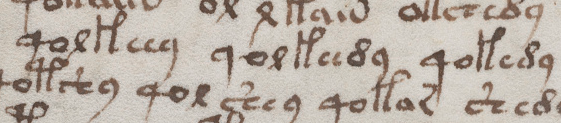

This example, from the following folio might appear to be a sequence of five (with only one change in each), except that the differences in EVA-t and EVA-k create two changes rather than one:

Here’s a similar sequence with dar and dax at beginning and end and four very similar tokens in between:

There’s no rule in charms that limits changes to only one letter, but when studying an unknown text like the VMS, if you give yourself too many degrees of freedom, you may be biasing your results. It’s usually better to examine simple changes first and, depending on what they reveal, go from there.

What we frequently find in the VMS is sequences where two glyphs change from one to the next. What is especially interesting about these sequences is that the characters that create two changes rather than one are often EVA-t and EVA-k.

The word oladaba8 on 116v is similar to some of the variants on abracadabra. Here is a full phrase found in Grimoires:

ala drabra ladr[a] dabra rabra afra brara agla et alpha omega

Now if we take the first part (before the readable part that says “agla et alpha omega”) and reverse it (something that was frequently done with magical words), we get

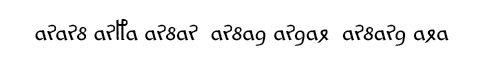

ararb arfa arbar arbad ardal arbard ala

If we substitute VMS characters with similar shapes, we get something close to Voynichese:

It’s not legal Voynichese (it’s too repetitive, there are other ways it could be substituted, and it breaks a couple of rules), but it shows some provocative similarities between Voynichese and charm sequences that are difficult to find between Voynichese and natural languages.

A French book of medicine from the early 19th century mentions both abracadabra and its reverse arbadacarba. In turn, if you break up arbadacarba into ar sa da 8ar sa (or something along those lines), the similarities to VMS components are more evident.

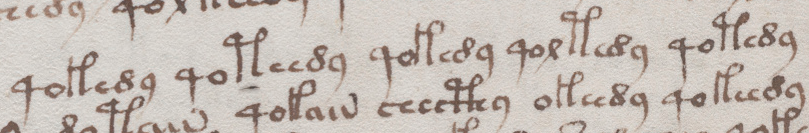

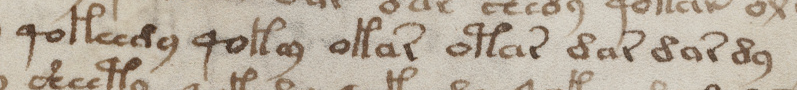

Remember the reduction charms I mentioned at the beginning? Where a charm word is broken down into smaller and smaller bits? Here is another interesting sequence in the VMS:

No, it’s not exactly the same in terms of which letters are dropped, but the way it diminishes is more similar to charm reductions than it is to the way sentences are usually constructed. Reduction-style charm sequences don’t follow hard-and-fast rules, just general guidelines (note that these patterns are more prevalent in some sections of the VMS than others).

Summary

There are not enough VMS glyphs with talismanic shapes to prove a connection to books of kabbalah or western magic. There’s only one (EVA-t) that is not easily found in the Greco-Roman scribal repertoire. My research tells me that most VMS glyph-shapes are the same shapes as Latin letters, numbers, and abbreviations (with a few that resemble Greek).

Also… to suggest that the VMS is full of enciphered charm words would be to ignore line-complexity, and the great variety of sequences that comprise the text. It’s possible that VMS patterns are generated in another way and similarity to charms is coincidental.

But there are portions that resemble charms in terms of pattern, repetition, and successive lengths of tokens, so perhaps some parts of the manuscript were inspired by incantations or charms. The only way to find out is to study them to see where and how often they occur.

J.K. Petersen

© Copyright February 2020, J.K. Petersen, All Rights Reserved