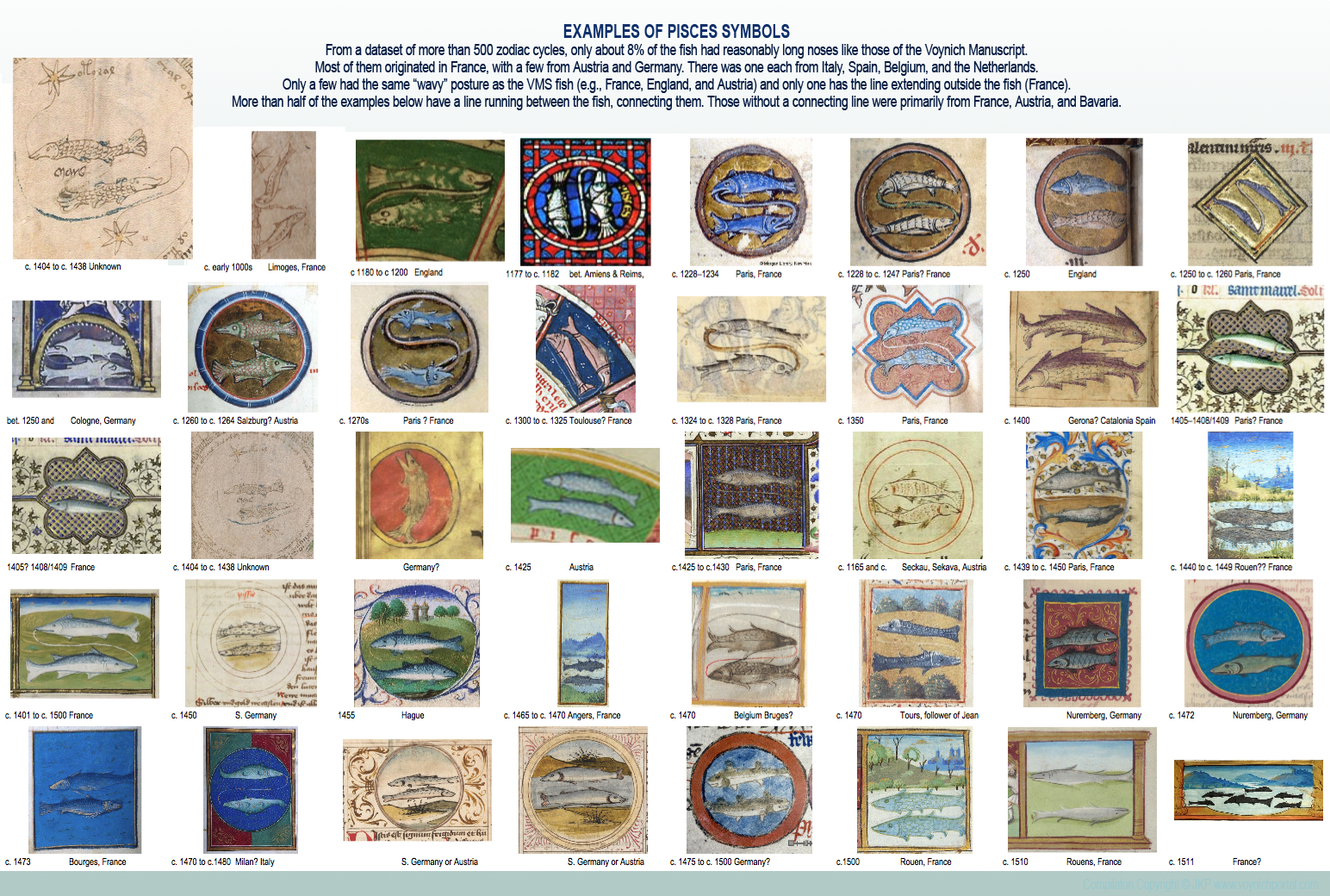

I’ve posted several blogs on hats and tunics and the VMS Gemini tunic is now being discussed in depth on the voynich.ninja forum, so it’s clearly a topic of interest. I’ve been researching the clothing of the zodiac figures for a number of years, so I have many examples from a large variety of sources (including mosaics and stained-glass windows), but I thought I would focus on fashion in two specific manuscripts.

I see the VMS zodiac tunics and robes as belonging together in terms of style.

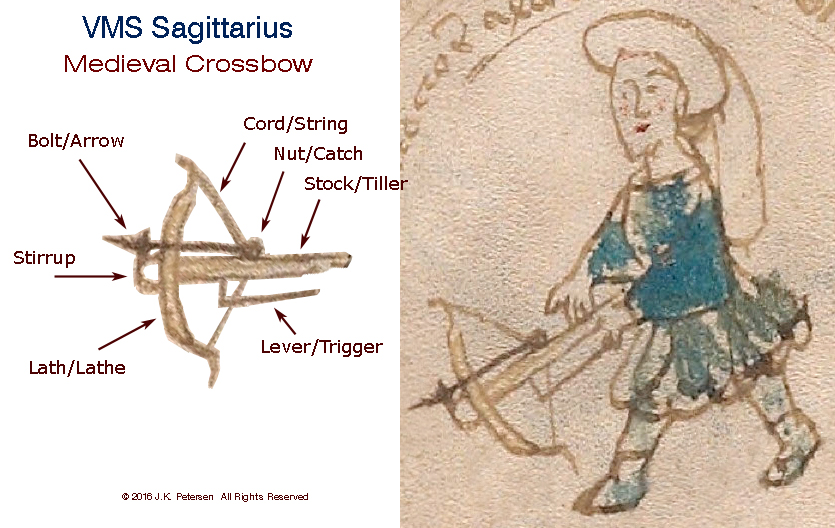

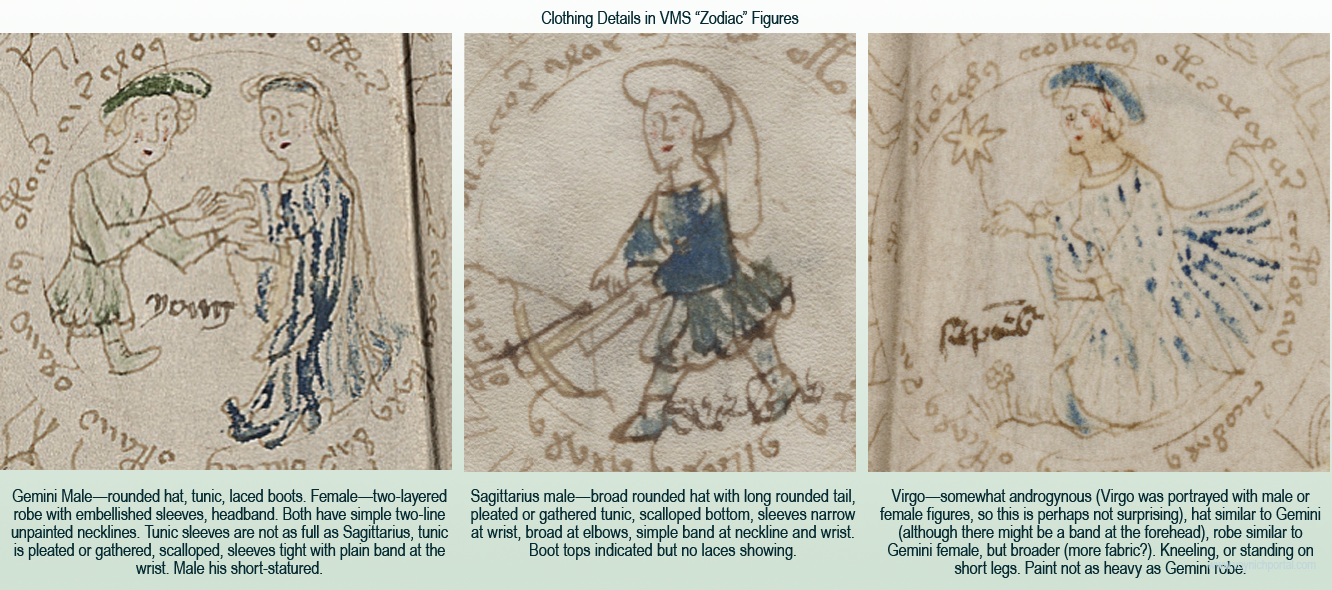

- Both male-Gemini and Sagittarius wear basic tunics with simple double-line neckbands, both are wearing hats, Gemini a simple rounded hat, Sagittarius a hat with a very long rounded tail (similar to a foxtail hat, but with fabric rather than fur). Sagittarius has the hint of a goatee. Note that Gemini is conspicuously short-statured even though there’s room to make the leg longer.

- Both females (assuming the slightly androgenous Virgo is female) are wearing long robes with embellished sleeves and the hint of an undergarment peaking out from under the outer sleeve:

The clothing in Vatican Pal.lat.871 has been mentioned before, because it has many commonalities with the VMS figures.

The clothing in Vatican Pal.lat.871 has been mentioned before, because it has many commonalities with the VMS figures.

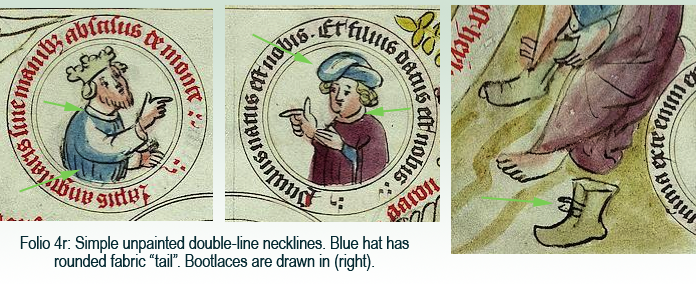

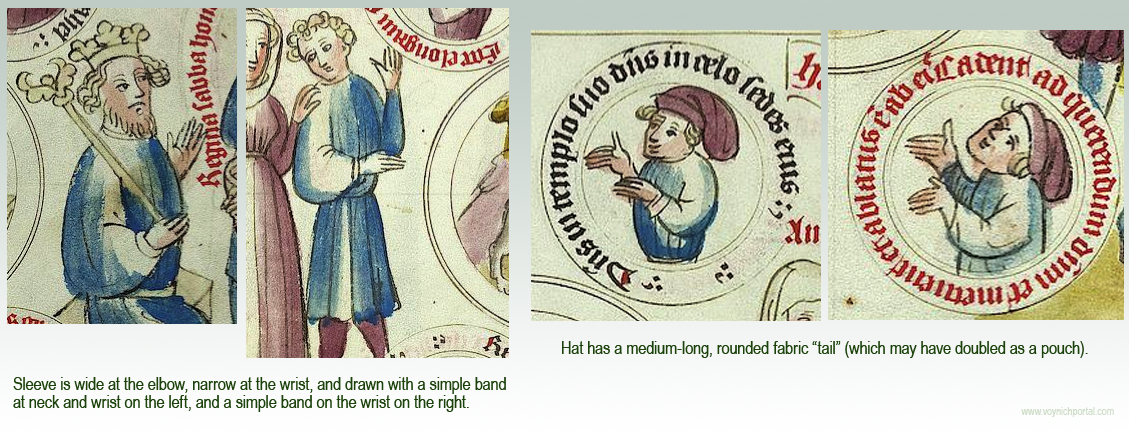

Here are examples from folio 4r. The subject matter is quite different from zodiacs, it’s a nativity scene, but the roundel-with-text presentation, drawing themes, and clothing have VMS parallels in necklines, gathers, and the hard-to-find bootlaces:

It’s possible that the round-tailed style of hat doubled as a carrying pouch since tunics generally did not have pockets. Small items were strapped to belts, carried on the back, or slipped into hat bands or pouches. The VMS hat does not look like an animal tail. Note that many of the neckbands are similar to the VMS (a plain double-line band), even though a variety of necklines are represented:

It’s possible that the round-tailed style of hat doubled as a carrying pouch since tunics generally did not have pockets. Small items were strapped to belts, carried on the back, or slipped into hat bands or pouches. The VMS hat does not look like an animal tail. Note that many of the neckbands are similar to the VMS (a plain double-line band), even though a variety of necklines are represented:

There are also tunics with bumpy or scalloped edges like those in the VMS:

There are also tunics with bumpy or scalloped edges like those in the VMS:

One can also find sleeves that are narrow at the wrist and wide at the elbow (left), which is less common than sleeves that are mostly even or much wider at the wrist:

The illustrator was definitely making distinctions in dress. Not all collars were a simple band, there were also high collar, capes, and cowls. Tunics were sometimes single-layer, sometimes double.

The illustrator was definitely making distinctions in dress. Not all collars were a simple band, there were also high collar, capes, and cowls. Tunics were sometimes single-layer, sometimes double.

There are also many hat styles in addition to the “pouched” hat, including Phrygian hats, royal crowns, tonsured monks, berets, bowlers and, since this is a biblical text, pointed and flat hats to represent Jews and Philistines:

The drawings in Pal.lat.871 make it look like the “pouch” style of hat was common, but it is not easily found in medieval manuscripts. Usually, the tail was an animal tail or the ends were ragged, like a cock’s comb. Pouched hats with very long tails, like VMS Sagittarius, are especially hard to find, although I previously posted this one from Morgan M.453 (left) and one from a Swedish book of law that has a fairly long tail, with a conspicuous roll for the band:

Getting Back to Tunics

Many of the robes in Pal.lat.871 are long or have simple edges, but there are also tunics that are distinctly pleated (e.g., some of the warrior tunics, left) and some that are drawn with a bumpy, gathered, or scalloped edge, like the VMS:

So we can see numerous parallels to VMS clothing styles throughout the manuscript, not just in one or two places.

Finding the Origin of the Manuscript

I was curious about who drew the illustrations.

Pal.lat.871 is written in German, and I noticed it was a dialect. It is thought to be from central Germany, possibly north Hessen (near Frankfurt) or west Thuringia (about midway between Frankfurt and Prague). There is a woodcut version of the Pauper’s Bible created nearby in Bamberg, just north of Nuremberg (c. 1460s) with some of the same clothing styles.

I don’t know if it is specific to the illustrator, but there’s a political statement on folio 16r, a nimbed figure holding the battle banner of the Scandinavian tribes. This puzzling image is sandwiched between Sampson carrying tablets and Jonah in the mouth of the whale. It’s the only roundel on the folio without text.

In manuscript art, the white cross on a red field frequently represents the Lombards or Danes. The inverse of this flag, a red cross on a white field, often represented Helvetians, Templars, or participants in the Crusades. By the time this manuscript was created, Lombardian rule had long since diminished, and Lombardy itself had receded from Florence north to Pistoia, but it still dominated what is now northern Italy, and there were still pockets in Germany, Switzerland, and southern Italy.

But, I have also seen the white-on-red flag in drawings of 14th-century “Gaisler” (Geißler), Christian flagellants associated with the plague years.

Perhaps a sister manuscript can shed some additional light on origins.

A More Primitive Drawing Style

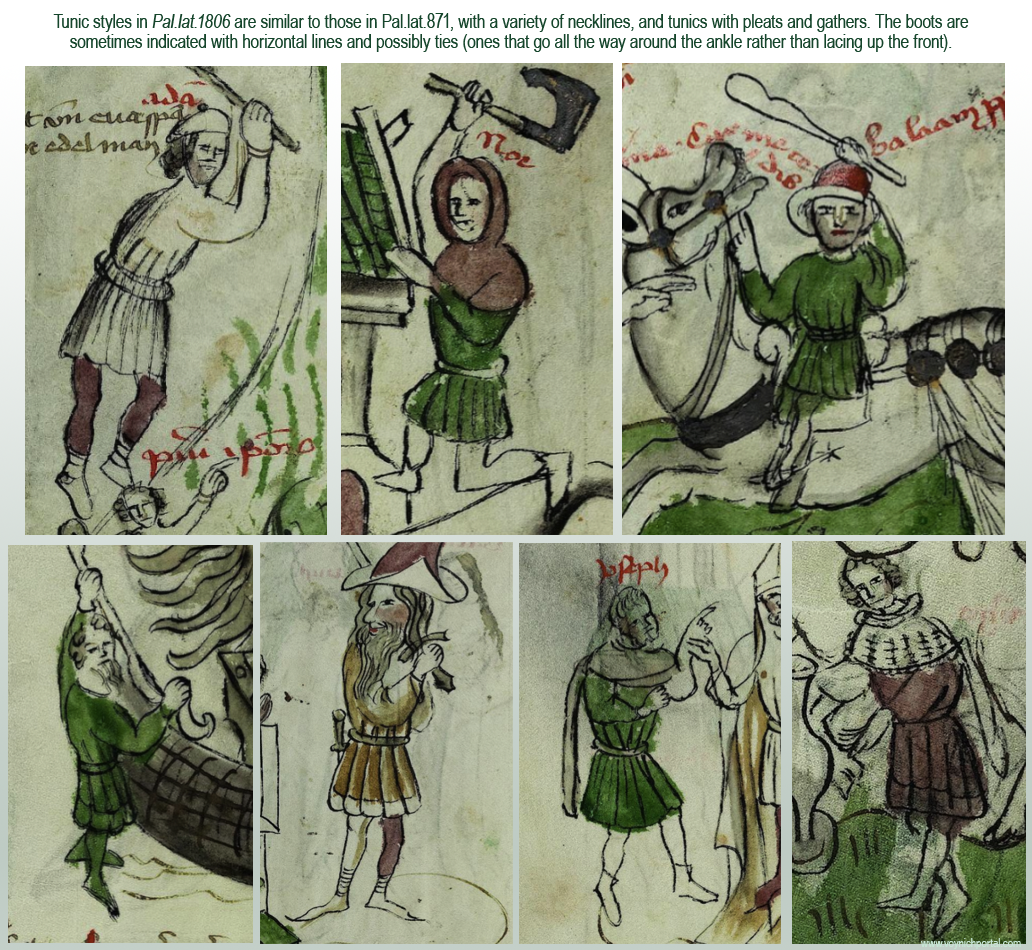

Vatican Pal.lat.1806 was created at approximately the same time as Pal.lat.871 and has very similar clothing themes. It is interesting because the illustrator’s skill level is a little less accomplished than Pal.lat.1806 and thus closer to that of the VMS. Here are some examples of tunics:

There are also sleeves that are narrow at the wrist and wide at the elbow, but they tend to be paired with fancier tunics. Here are some of the simpler ones

Also, if you keep looking, you can find the Sagittarius “pouched” hat. The hat (right) in Pal.lat.871 is not just a vague or generic drawing, it is drawn in a distinctively different way from the ragged-fabric chaperone on the left:

Pal.lat.871 and Pal.lat.1806 are thought to be from different towns, and are drawn by illustrators of different skill levels, yet the clothing themes are clearly related and, in turn, are similar to the VMS zodiac costumes.

Drawing Skill and Cultural Differences

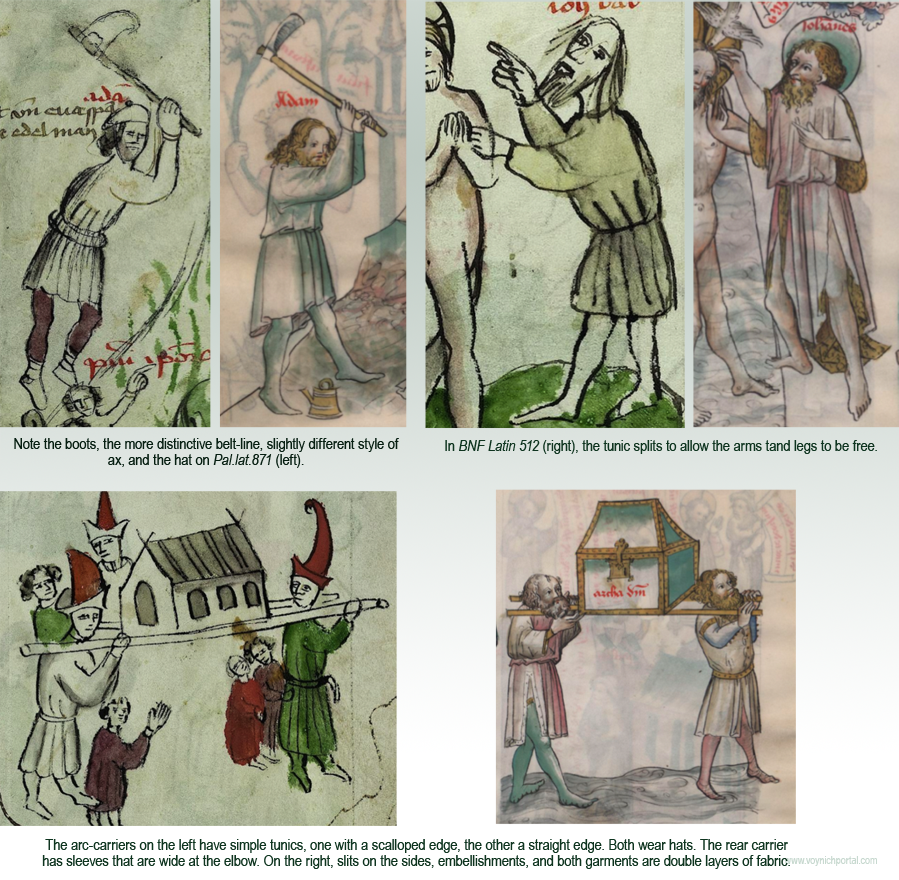

What happens if the same subject matter is interpreted by someone from a different culture and significantly better artistic skills? Do the tunics change? That’s a subject for a separate blog, but I’ll include a few examples to introduce the topic. On the left, from Pal.lat.1806 and on the right, the same scene from BNF Latin 512:

Here some more specific tunic comparisons between Pal.Lat.871 and BNF Latin 512, both of which are from approximately the middle or third quarter of the 15th century:

As might be expected, there are more details in the drawing by the better artist, but paging through the manuscripts side-by-side, there also appear to be small cultural differences that are probably related to the difference in German and French origins. In terms of clothing style and drawing skill, the VMS is obviously more similar to Pal.lat.1806 than BNF Latin 512.

Summary

I have much more on this subject, and don’t have enough space to post about the female dress in the same blog. For the moment, there are enough examples to illustrate that the two German manuscripts Pal.lat.871 and Pal.lat.1806 (in addition to those mentioned in previous blogs), bear notable similarities to the costumes of the VMS zodiac characters.

J.K. Petersen

© Copyright 2018 All Rights Reserved