12 Jan 2016

Discerning a Big Picture from Small Clues

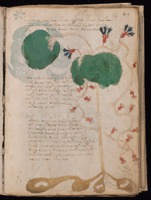

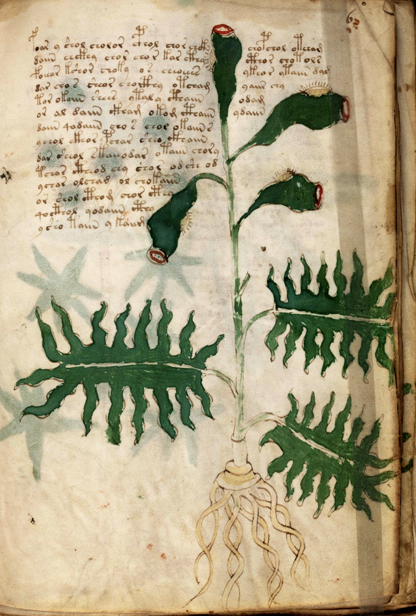

The zodiac pictures in the Voynich don’t appear to have much to do with zodiacs, they are mostly surrounded by ladies in loges, but the images themselves are recognizable as traditional zodiac symbols.

The depiction of Sagittarius in the Voynich manuscript as having legs and a crossbow is unusual and is, for the most part confined to a certain time and place, with the time being contemporaneous with the creation of the VMS. Since details like this may offer clues to the identity of the author or provenance of the document, it seemed worthwhile to examine some of the other symbols as well.

The Scorpio Zodiac Symbol

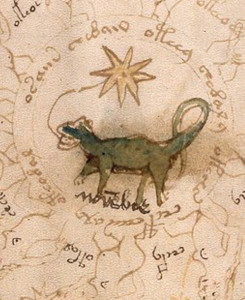

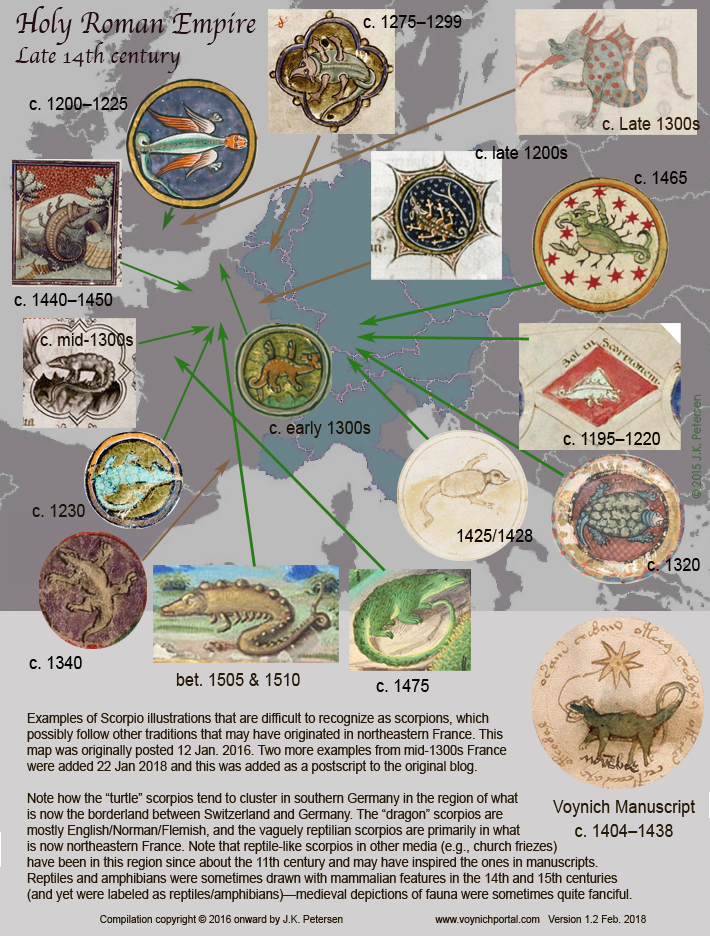

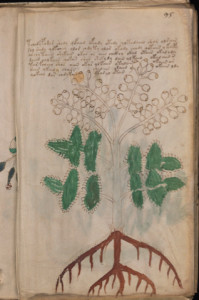

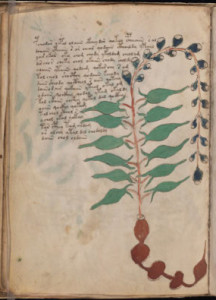

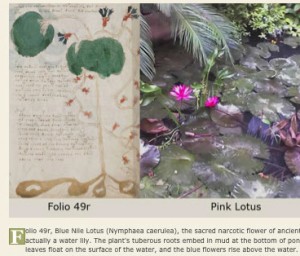

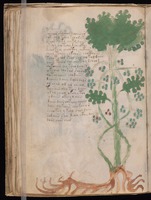

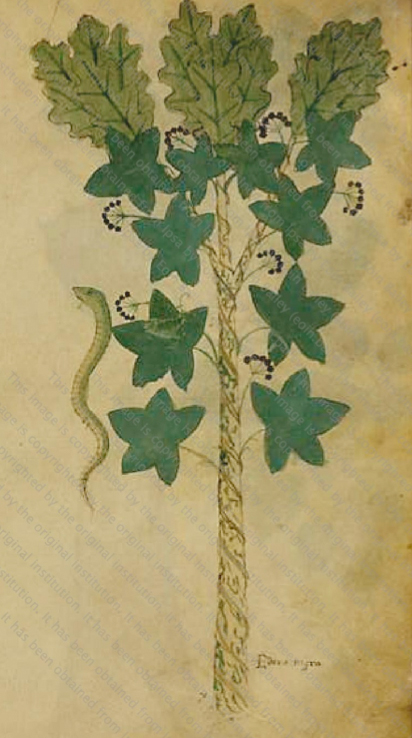

Folio 73r features a lizard-like yellowish-green creature with a long tail and a line in its mouth leading to a drawing of an 8-pointed star. It is surrounded by successive circles of texts and naked women.

Folio 73r features a lizard-like yellowish-green creature with a long tail and a line in its mouth leading to a drawing of an 8-pointed star. It is surrounded by successive circles of texts and naked women.

It’s assumed this is Scorpio because it would fit the overall theme of zodiac symbols on adjacent pages. Whoever labeled the creature in a hand that differs from the main body text of the VMS, apparently thought so too, and labeled it novembre.

Many medieval European ideas about astrology and astronomy came from concepts expressed in Arabic documents.

Many medieval European ideas about astrology and astronomy came from concepts expressed in Arabic documents.

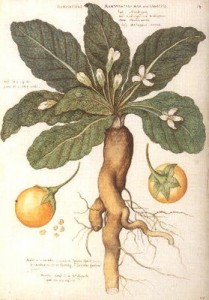

Scorpio is based on the constellation Scorpius, a clump of stars with a long curving chain of a tail that resembles a scorpion, a venomous creature in the same family as spiders. You might not guess it was cousin to spiders, because it resembles a crustacean more than a spider (picture a crayfish with an upcurved, pointed tail). Depending on the species, the scorpion has six or eight legs plus specialized pointed claws called pedipalps, and a distinctive claw-like stinger at the end of the tail.

Today, scorpions have spread to almost every part of the world. In the middle ages, however, they may have been infrequent (or absent) in northern latitudes because illustrators who did a good job of drawing the other zodiac symbols sometimes created fanciful versions of Scorpio, or perhaps retained a different concept of the animal that the Scorpius constellation resembled because they were unfamiliar with the creature after which it was named.

That’s not to say that all northern Scorpios were difficult to recognize as a scorpion, many were quite accurate, as can be seen by the examples above that range from about 1425 to the later 1400s, but there are a few that deserve attention because, like the Voynich Scorpio, they could easily be mistaken for lizards, mammals, or dragons.

That’s not to say that all northern Scorpios were difficult to recognize as a scorpion, many were quite accurate, as can be seen by the examples above that range from about 1425 to the later 1400s, but there are a few that deserve attention because, like the Voynich Scorpio, they could easily be mistaken for lizards, mammals, or dragons.

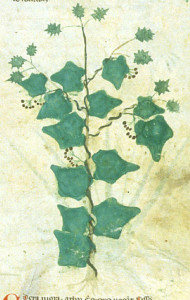

Unusual Depictions of Scorpio

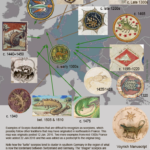

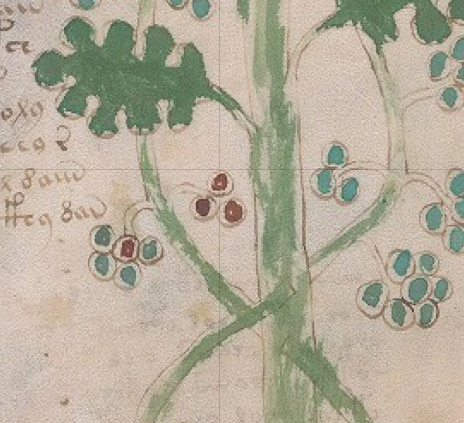

The following chart illustrates some unusual depictions of Scorpio that would be difficult to recognize unless they were labeled as such or included with the other traditional zodiac symbols for context.

Naturalistic Scorpios are far more common than examples like these. Note that the origins of unusual Scorpio symbols trends more to the north and west than Sagittarius with a crossbow and legs. There is noticeable clustering of Sagittarius in the southern German and northern Swiss area. In contrast, the unusual Scorpios range from Germany and Switzerland to France and England. The two examples from England look more like mythical creatures (perhaps dragons) than any natural animal.

Naturalistic Scorpios are far more common than examples like these. Note that the origins of unusual Scorpio symbols trends more to the north and west than Sagittarius with a crossbow and legs. There is noticeable clustering of Sagittarius in the southern German and northern Swiss area. In contrast, the unusual Scorpios range from Germany and Switzerland to France and England. The two examples from England look more like mythical creatures (perhaps dragons) than any natural animal.

I haven’t yet found any reptilian or mammalian Scorpios from eastern Europe or the Mediterranean. They may exist, but if they do, they are not common. There are some that are debatable because they are not of expert quality. I tried to steer away from illustrations where you really can’t tell whether Scorpio’s quirks were a deliberate choice or attributable to weak drawing skills, and concentrated on those that were drawn well enough or deliberately enough to classify them as one or the other.

The date range of odd Scorpio symbols is not as tight as Sagittarius. Sagittarius with legs and a crossbow tends to occur very close to the time the VMS was created (estimated to be in the early 1400s). Unusual Scorpios, however, range from about 1200 to the early 1500s and since they are rare, are more broadly separated in time. In fact, only one Scorpio in this sampling is contemporaneous to the VMS.

Drawing Conventions

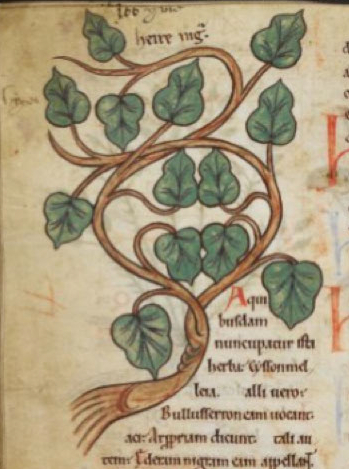

There are three examples that cluster around the German-Swiss border that resemble turtles and which don’t resemble the VM Scorpio at all. Give the scarcity of turtle-Scorpios and their geographic proximity, you might expect them to originate around the same time, but they were actually created about 100 years apart.

The two examples that most closely resemble the side-on posture, orientation, and lizard-like qualities of the VMS were created about 70 years earlier and about 80 years later than the estimated time of the VMS. There’s little likelihood that the brownish Scorpio with stegosaurus-like bumps influenced the VM since it was probably created later and has numerous legs, but it’s possible the one from the mid-1300s did if it was stored in a library or other location where people had access to the manuscript.

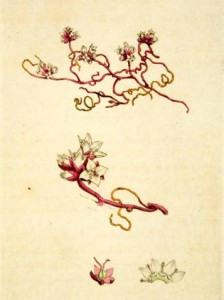

The green one from c. 1475 was probably created after the VMS, but note that both the VMS Scorpio and the green Scorpio from France have spots on their backs. There are a number of lizards, native to Portugal, Spain and southern France that are green with spots. Perhaps there was an oral tradition for the names of the constellations that influenced the choice of a lizardy creature that actually lived in north or central Europe.

The green one from c. 1475 was probably created after the VMS, but note that both the VMS Scorpio and the green Scorpio from France have spots on their backs. There are a number of lizards, native to Portugal, Spain and southern France that are green with spots. Perhaps there was an oral tradition for the names of the constellations that influenced the choice of a lizardy creature that actually lived in north or central Europe.

Other Astrological Traditions

When you consider that most Scorpio symbols in the 15th century looked fairly realistic, even those from the north, you have to wonder why the Voynich illustrator chose this form. In some cultures, the stars that form Scorpius are perceived as a palm tree or as a bird, by why a lizard or mammal?

I considered that depictions of Scorpio in the north might be influenced by Nidhogg, a Norse serpent constellation that shares some stars with Scorpio but the resemblance is slight. The serpent is very long and doesn’t have legs. So, it appears that the Voynich manuscript, as it does in so many respects, serves up another mystery, one deserving of further study.

J.K. Petersen

© Copyright 2016 J.K. Petersen, All Rights Reserved

Postscript 23 Jan. 2018: I have added two more images to the map from manuscripts that originated in the mid-14th century—one from Thérouanne and the other with shelfmark H 437 (which was brought to my attention in a post by Marco Ponzi).

I am not certain where H 437 originated, but the Picard-dialect translation of the Bestiary has been variously attributed to Richard or Pierre de Beauvais sometime in the early 13th century. H 734, the c. 1341 version, is housed in the Montpellier library but possibly originated farther north.

I am not certain where H 437 originated, but the Picard-dialect translation of the Bestiary has been variously attributed to Richard or Pierre de Beauvais sometime in the early 13th century. H 734, the c. 1341 version, is housed in the Montpellier library but possibly originated farther north.

There isn’t room on the map to include the reptilian scorpios from other media dating back to the 11th century, but I have referenced sculptures, stained glass, and mosiac images in previous blogs about the constellation (I was not able to include images of all the sculptures due to copyright restrictions).

Postscript 2 Feb. 2018: I’ve been trying not to clutter this image too much, but I managed to squeeze one more example on the map (from c. 1230), and I have added a version number. I have many “dragon” scorpios from England, but since they are somewhat different from most of the reptile/amphibian drawings from France, I have opted to include only a few for reference.

Postscript 2 Feb. 2018: I’ve been trying not to clutter this image too much, but I managed to squeeze one more example on the map (from c. 1230), and I have added a version number. I have many “dragon” scorpios from England, but since they are somewhat different from most of the reptile/amphibian drawings from France, I have opted to include only a few for reference.

As mentioned in the original blog on Scorpius, the green arrows are for reasonably established origins, with brown for those that are not completely certain.

You can click the thumbnail to see a larger version.

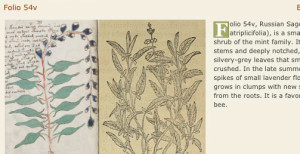

Description

Description