Tracing Taurus

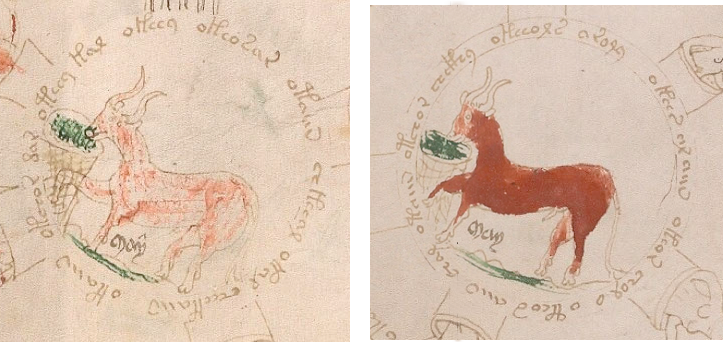

A drawing of a long-horned animal appears in the position one would expect to see Taurus the bull in a traditional zodiac sequence, and appears twice in the Voynich Manuscript, each within the center of a wheel populated with figures.

The two critters have some minor discrepancies, but are basically the same, except for the way in which they are painted. The brick-red paint is sketchy and light on one, darker and more even on the other. The information circling the figures differs, both textually and visually, but this post will concentrate on the imagery. Let’s compare them to a historic image of a bull:

The two critters have some minor discrepancies, but are basically the same, except for the way in which they are painted. The brick-red paint is sketchy and light on one, darker and more even on the other. The information circling the figures differs, both textually and visually, but this post will concentrate on the imagery. Let’s compare them to a historic image of a bull:

The most significant difference between the VMS bull and the one shown above is the shape of the neck. The VMS horns are also a bit more upright and closer together, but this was not unusual in medieval zodiacs. The other differences between the VMS bull and real bulls can probably be attributed to limited drawing skills.

The most significant difference between the VMS bull and the one shown above is the shape of the neck. The VMS horns are also a bit more upright and closer together, but this was not unusual in medieval zodiacs. The other differences between the VMS bull and real bulls can probably be attributed to limited drawing skills.

It should also be noted that the VMS bull appears to be standing in front of or eating from a basket-like container. The lines on the baskets are respectively diagonal and square. The face of the second bull is turned slightly more to the side. The month-name “May” has been written between the legs, probably by another hand, perhaps by someone trying to decode the manuscript.

Background on the Bull

I was curious about how closely the VMS bull resembles other illustrations of Taurus and collected more than 500 zodiac cycles so I could look for precedents and trends. I discovered that images of Taurus vary widely in style and color, and long curved horns are not uncommon on bulls that inhabited Europe and Asia in the middle ages, but the long neck that is more reminiscent of a deer, goat, or horse than a bull provoked my curiosity and I wondered whether there were others drawn the same way.

I was curious about how closely the VMS bull resembles other illustrations of Taurus and collected more than 500 zodiac cycles so I could look for precedents and trends. I discovered that images of Taurus vary widely in style and color, and long curved horns are not uncommon on bulls that inhabited Europe and Asia in the middle ages, but the long neck that is more reminiscent of a deer, goat, or horse than a bull provoked my curiosity and I wondered whether there were others drawn the same way.

Many of the oldest depictions of Taurus, from about the 1st and 2nd centuries CE, show the bull leaping to the right (and may not include the hindquarters, as the stars in the hind area were not considered part of the constellation). In others, the full animal is shown and may be facing either direction. In later centuries, Taurus is more docile, sometimes not running at all, perhaps reflecting a transition from wild to domesticated cattle.

Leaping Taurus with a hump, from the Hamat Tiberias synagogue floor mosaic, c. 300 BCE. The 9th century Tetrabiblos bull is very similar except there is less emphasis on the hump.

The early images, usually executed in stone or tile, are quite naturalistic and easily recognized as bulls. Many have humps, as is characteristic of certain species such as Brahman bulls. The hump shows up less frequently in later zodiacs.

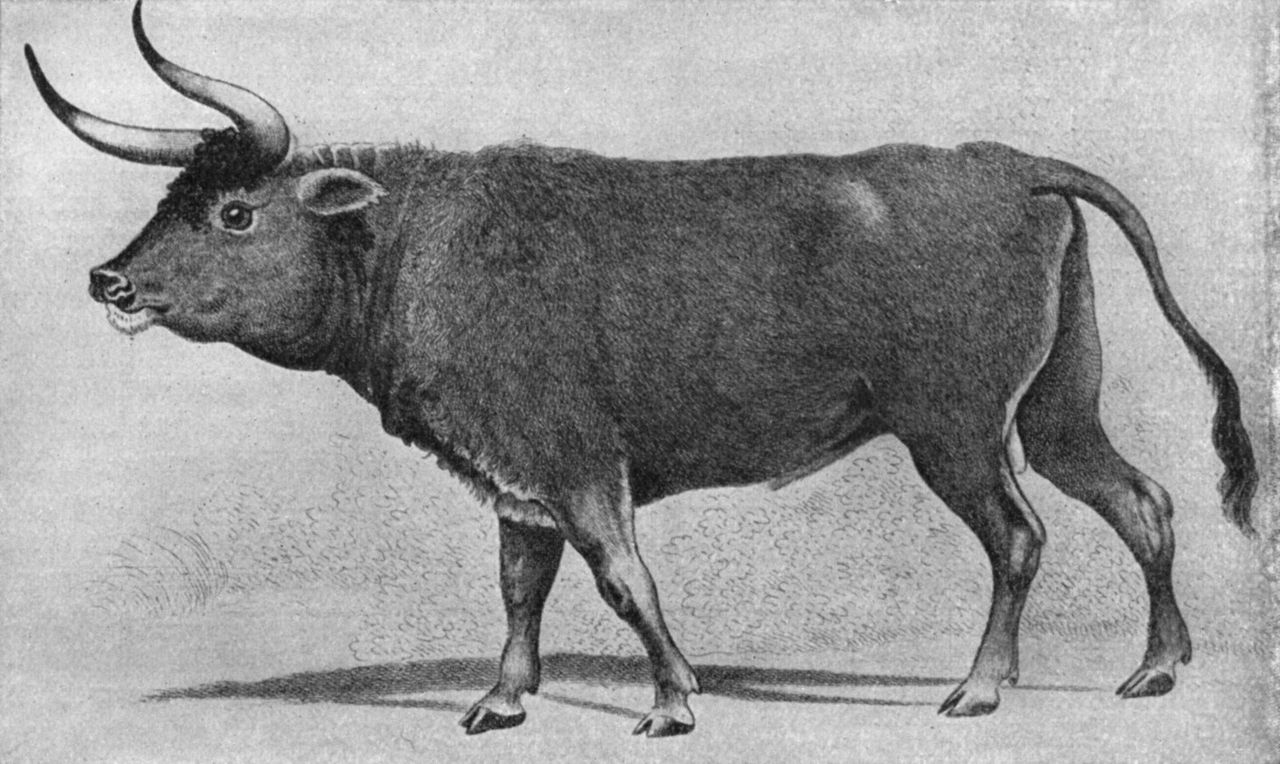

Humped bulls are thought to have originated from a central Asian aurochs, a form of cattle that had spread to the Mediterranean area by at least about 2,000 BCE. The European aurochs, an aggressive trophy animal with long curved horns, is possibly the one depicted in ancient cave paintings, and was still living in the wild during the middle ages, but unfortunately became extinct in 1627 when the last cow, living in a forest in Poland, was killed by a poacher.

Images of Taurus in the early Persian manuscripts were usually white with black spots or vice versa, often with a prominent hump, while the European Taurus was typically solid colors in beige, brown, black, or red, sometimes with a hump, sometimes not.

Images of Taurus in the early Persian manuscripts were usually white with black spots or vice versa, often with a prominent hump, while the European Taurus was typically solid colors in beige, brown, black, or red, sometimes with a hump, sometimes not.

By the 15th century, Arabic manuscripts frequently included solid-color bulls, as well.

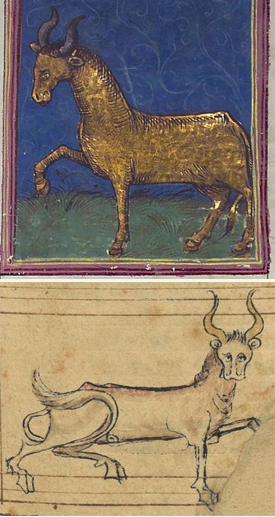

The drawing of Taurus on the right, from a 9th-century manuscript from the Monastery of Reichenau, Germany, differs from typical bulls in being more slender and graceful (possibly a stylistic preference of the illustrator who also drew slender Aries and Leo). From this point on, most images of Taurus did not feature a prominent hump.

The drawing of Taurus on the right, from a 9th-century manuscript from the Monastery of Reichenau, Germany, differs from typical bulls in being more slender and graceful (possibly a stylistic preference of the illustrator who also drew slender Aries and Leo). From this point on, most images of Taurus did not feature a prominent hump.

The 12th-century Hyginus Taurus from France (left) and a 12th-century Taurus from Augsburg, Germany, are similar to the Reichenau Taurus in being slender with long horns—but differ in having necks that are uncommonly narrow, similar to the VMS. The Taurus symbol from the Gallia Liber floridus has extravagantly long curved horns and the suggestion of a hump.

The 12th-century Hyginus Taurus from France (left) and a 12th-century Taurus from Augsburg, Germany, are similar to the Reichenau Taurus in being slender with long horns—but differ in having necks that are uncommonly narrow, similar to the VMS. The Taurus symbol from the Gallia Liber floridus has extravagantly long curved horns and the suggestion of a hump.

Some bulls are stylistically embellished with dashes and dots, like this long-necked red Taurus from Weingarten, Germany (right), but are still essentially a solid color. Note, this is a very rare instance of Taurus without horns (Morgan m.711). There is also a bright red Taurus in a manuscript from Augsberg, Germany, from around the same time.

Some bulls are stylistically embellished with dashes and dots, like this long-necked red Taurus from Weingarten, Germany (right), but are still essentially a solid color. Note, this is a very rare instance of Taurus without horns (Morgan m.711). There is also a bright red Taurus in a manuscript from Augsberg, Germany, from around the same time.

Giorgio Armani would approve of this stylish 13th-century Parisian Taurus stepping out in a bright blue suit with a gold-leaf background (Morgan m.92). Note that this bull also has a fairly long neck, although it doesn’t have long curved horns. The tail coming out from between the legs is a stylistic choice that is usually reserved for Leo, but is occasionally seen on Taurus, as well.

Giorgio Armani would approve of this stylish 13th-century Parisian Taurus stepping out in a bright blue suit with a gold-leaf background (Morgan m.92). Note that this bull also has a fairly long neck, although it doesn’t have long curved horns. The tail coming out from between the legs is a stylistic choice that is usually reserved for Leo, but is occasionally seen on Taurus, as well.

Sometimes solid colors are applied with a lighter touch to create a shaded look or the illusion of a lighter pigment, as in this long-horned bull from the mid-13th century (Morgan m.730). There are places in the Voynich Manuscript where the paint has been brushed on very lightly, as well, as though the painter might have been trying inexpertly to achieve the effect of a softer-color pigment.

Sometimes solid colors are applied with a lighter touch to create a shaded look or the illusion of a lighter pigment, as in this long-horned bull from the mid-13th century (Morgan m.730). There are places in the Voynich Manuscript where the paint has been brushed on very lightly, as well, as though the painter might have been trying inexpertly to achieve the effect of a softer-color pigment.

Artists can get pretty creative with whatever pigments they have at hand, and cattle vary widely in hide color, so it’s not surprising that Taurus has been painted almost every shade imaginable, but I was surprised to find slender bulls with long necks and long curved horns as often as I did. I wondered if this might be a local custom, limited to one area, but they don’t seem to be tied to any specific region.

Artists can get pretty creative with whatever pigments they have at hand, and cattle vary widely in hide color, so it’s not surprising that Taurus has been painted almost every shade imaginable, but I was surprised to find slender bulls with long necks and long curved horns as often as I did. I wondered if this might be a local custom, limited to one area, but they don’t seem to be tied to any specific region.

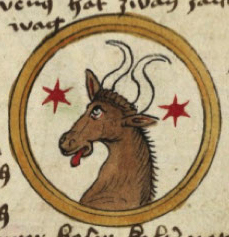

The thin-necked bull drawings are not frequent, but neither are they rare, as can be seen by the high-stepping examples to the left, so the long neck and horns on the VMS bull are not as distinctively different as I originally thought. Maybe the illustrators were unimpressed by bovine anatomy or less familiar with cattle than horses or deer, and drew according to what they knew.

Considering Other Details

The detail that makes the VMS stand out as different is not so much the bull as the basket. It’s very unusual for a basket to be included with Taurus—cattle usually graze unless it’s a very arid region. Sometimes there are trees and shrubs in the background with Taurus, but it’s difficult to find even one incidence of a basket, except when month’s labors have been combined in the same drawing with a zodiac sign, which is not the case with the VMS symbols.

The detail that makes the VMS stand out as different is not so much the bull as the basket. It’s very unusual for a basket to be included with Taurus—cattle usually graze unless it’s a very arid region. Sometimes there are trees and shrubs in the background with Taurus, but it’s difficult to find even one incidence of a basket, except when month’s labors have been combined in the same drawing with a zodiac sign, which is not the case with the VMS symbols.

Not only is a basket unusual, but the VMS illustrator gave each bull a different style of basket. Whether the basket is a whim (or misconception of bovine feeding habits) or a detail that might help identify the illustrator’s locale, is still to be seen.

J.K. Petersen

© Copyright 2016 J.K. Petersen, All Rights Reserved