7 November 2017

I’ve written several posts on the VMS bowman and didn’t think there was more to say about his bow, but after looking at hundreds of crossbows, I feel more strongly than ever that the origin of the Sagittarius bow might remain a mystery until the text is deciphered.

It’s difficult to find crossbows that originated before 1500. They’re made of natural materials that wear out or easily perish in fires. There are a few rare examples that are claimed to be from the late 15th century, but even those dates are speculative—a home-crafted bow from the 16th century can look very much like a typical 14th-century bow.

Crossbow artisans kept their trade secrets close to the vest, so most of what we know about crossbows was passed down by scribes and illustrators. Fortunately, a few descriptions are relatively detailed. Most of them, however, are not, including the drawing of a crossbow in the Quevedo Voynich Manuscript.

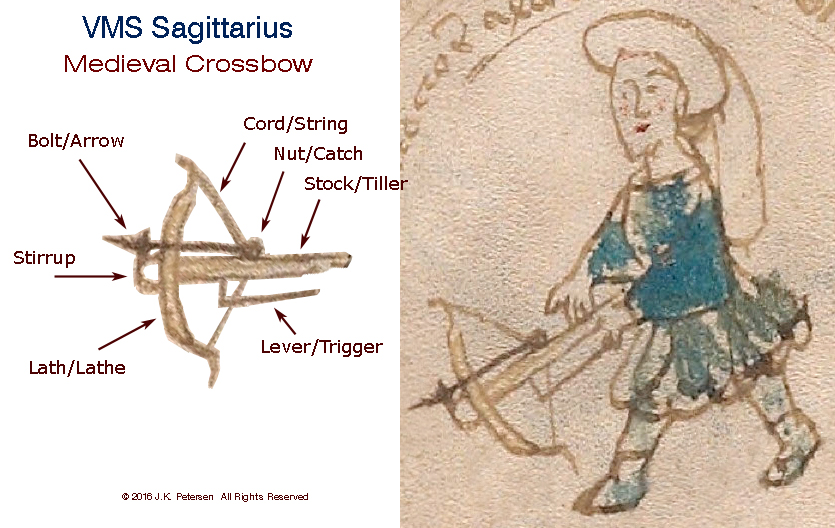

To recap, here is a picture the VMS crossbow that was previously posted to point out its main features. The shape of the stock-end is speculative, since it’s hidden by his hand.

In terms of locating the origin or time-period of the bow, there are four features of particular interest:

- the rounded stirrup,

- the long trigger,

- the extra curve at the tips of the lath (also called a prod), and

- the position of the nut or tumbler, also known as the catch (in a small, rough drawing it’s impossible to determine the style of catch).

Details of Interest

Lugs and Lath Tips

Most stocks in the Middle Ages were straight or narrowed. After the Renaissance, some evolved into gun-stocks like those on a rifle. Later bows were fitted with lugs for attaching a crank (these are usually positioned a couple of inches behind the nut), a feature that was less common in the 15th century, but quite prevalent by the 17th century.

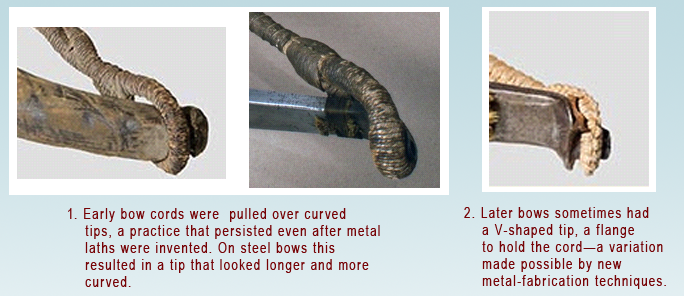

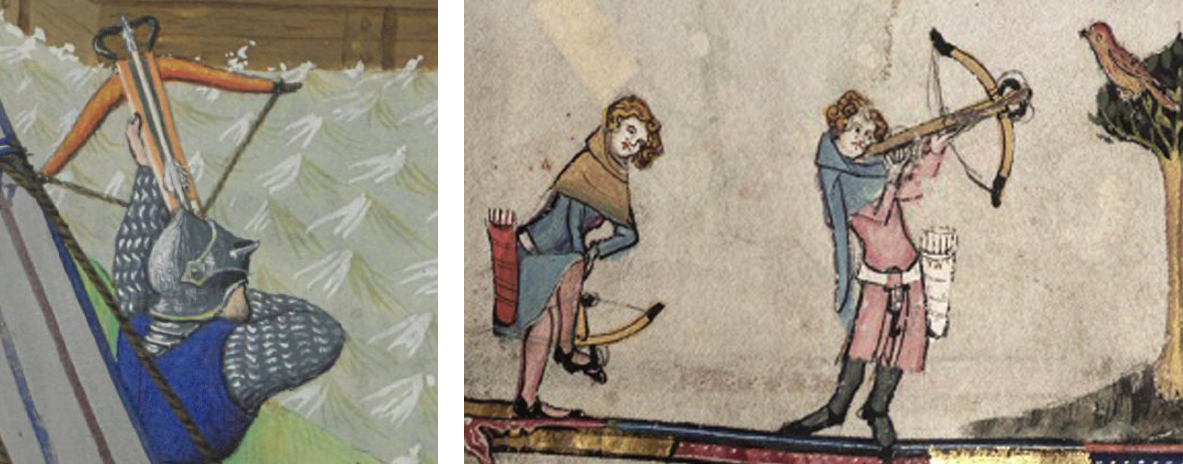

The VMS drawing is not detailed enough to show the style of cord, whether there were lugs, or how the stirrup was bound to the lath. It is interesting, however, that so much care and attention was given to the graceful curving tips at the end of the lath, a feature that was not common to crossbows (longbows didn’t always have long tips either). Medieval laths were usually wood, or composite materials such as wood and bone, with blunt tips, as in these examples:

Sometimes when the cord is quite thick it gives the appearance of longer tips (as in the center image that follows), but the VMS drawing doesn’t look like an extended cord—it looks like the tips of the lath extend beyond the wound cord.

So what could account for the relatively sharp lath-tips in the VMS crossbow?

Could the illustrator have combined features of the longbow and crossbow? Or might the lath have been made of steel (as in the two images to the right above), a material that was gradually introduced in the 12th century, but did not become widespread until the late 15th or early 16th century? Steel prods were narrower than composite, sometimes with longer tips.

Or maybe the answer is more complicated… the lath in the following picture looks like it could be composite materials (it is moderately thick), but the tips are quite narrow and very hooked, as though they were reinforced and extended by metal caps. I’m not aware of any historic prods with caps, and the glue would have to be very strong to hold against the pull of a loaded cord, so I looked for another explanation. Perhaps the bow in the picture was wrapped in a material like snakeskin, with the tips left unwrapped… but that still doesn’t account for the extra curve in the tips—these kinds of curves are not easily incorporated into wood or composite bows, and the tips become fragile if sharply tapered—a broken tip could lead to death on the battlefield or the loss of a week’s food on a hunting trip.

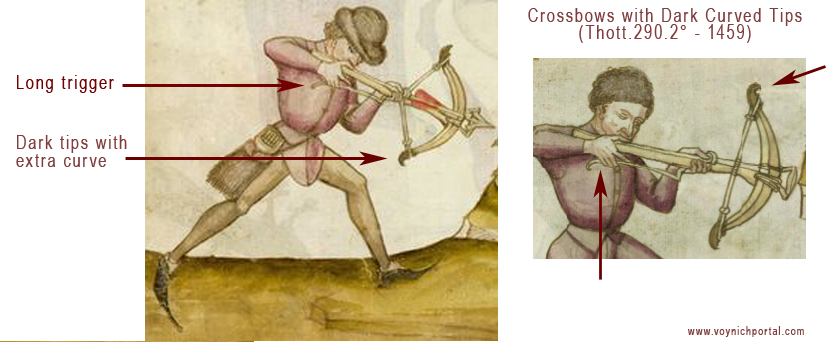

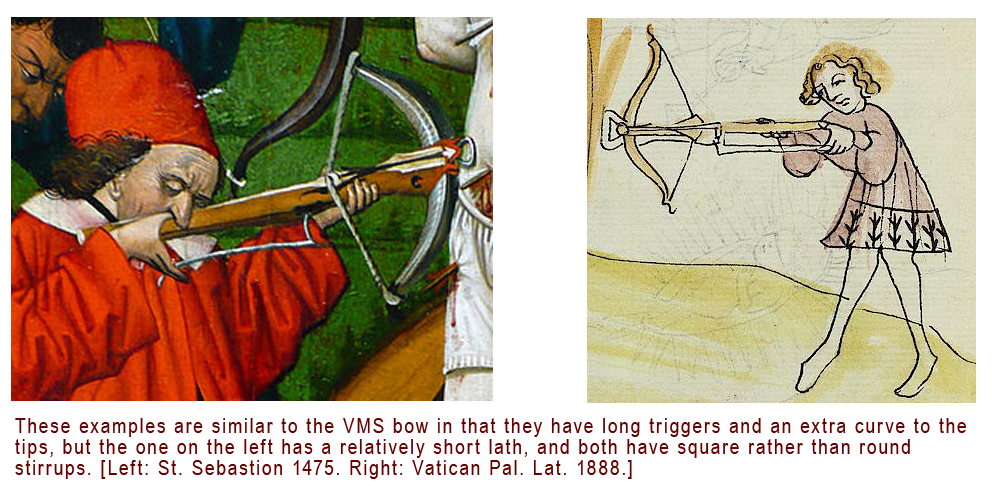

If the tips were “caps” rather than a protruding unwrapped part, these drawings from 1459 Moissy-Cramayel (Thott.290.2º) might illustrate a part of crossbow history that isn’t well documented. Either way, even if the curve is not literal, but simply an artistic embellishment, drawings like the VMS, with an extra curl in the tips, are definitely in the minority. I found very few compared to bows with blunt tips or only a slight curve. Here are some drawn with an extra curve:

Note how the laths in the Thott illustration above have darkened tips.

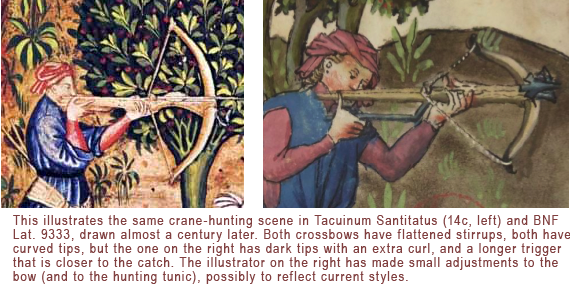

The following examples are the same crane-hunting scene from the Tacuinum Santitatus tradition, drawn by different illustrators almost a century apart. Except for drawing style, the later version is a fairly faithful reproduction of the storyline, but notice how the illustrator took time to change some of the details, like the sleeves of the tunic, and the color and shape of the crossbow tips:

The earliest example I could find of a relatively clear crossbow with slender long tips was in an ecclesiastical manuscript from the 11th century (BNF Latin 12302), probably from France. It doesn’t have a stirrup, however, and the trigger is almost vertical, in contrast to the mostly horizontal triggers of later crossbows:

I did locate a photo of a long-triggered steel bow from Portugal with slender tips curved a little more than average, from the late 1500s, but the stock extends a couple of inches beyond the lath, and there was no stirrup attached.

Coloration in Drawings of Medieval Crossbows

By the 15th century crossbow laths with dark tips are not uncommon. Here are examples of a battle bow from BNF Français 9342 and a hunting bow from Bodley 264, with darker tips. In these drawings, it looks like the bow might be wrapped (possibly with snakeskin) and the tips left unwrapped, as opposed to the tips being capped:

The VMS drawing doesn’t have dark tips but it does have a rounded stirrup, like the bow on the right.

Stirrups

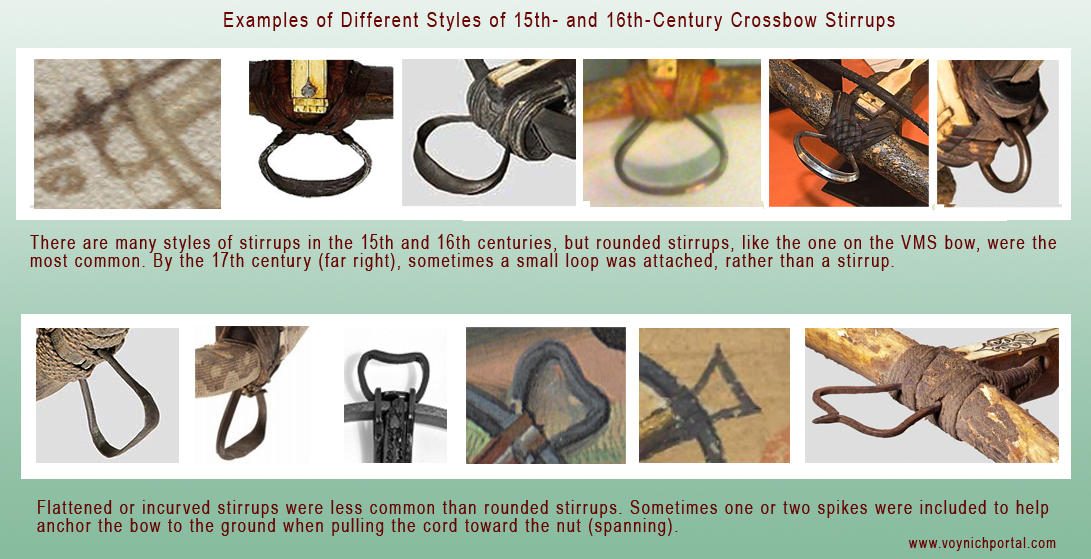

The rounded stirrup, the style in the VMS drawing, appears to be more common than squared-off stirrups:

When comparing the VMS bow to historic crossbows, keep in mind that they were functional items, subject to wear-and-tear, and the stirrup bindings and cords were replaced as they wore out. Thus, the stirrup itself may also have been replaced, especially if the original was lost due to disintegrated bindings, which were usually leather or cord. The nut would sometimes also break and be replaced with a slightly different style.

By the late 16th and 17th centuries, many crossbows, especially those for the nobility, showed significant artistry, with ivory, bone, laminate, and incised decorations along the full length of the stock. In the 17th century, pompoms (rounded tassels) were added to some of the laths. This remarkable bow from Dresden, Germany, has elaborately carved bear-hunting scenes, a tooled lath tip, and pom-poms. It dates to about the late 17th century or early 18th century (it has similar characteristics to a 1663 bow in The Met collection).

The VMS drawing shows no signs of decoration (possibly because it is so small), but judging by other medieval drawings, embellishments were less common in the 15th century than later.

And now to the important part… a little detail that is scarcely a blot on the drawing of the VMS stock.

Nuts

The catch to this whole VMS crossbow identification effort, is, well… the catch, the nut, the little protruding knob that secures the power of the spanned cord, like a capacitor, until the bowman releases its energy.

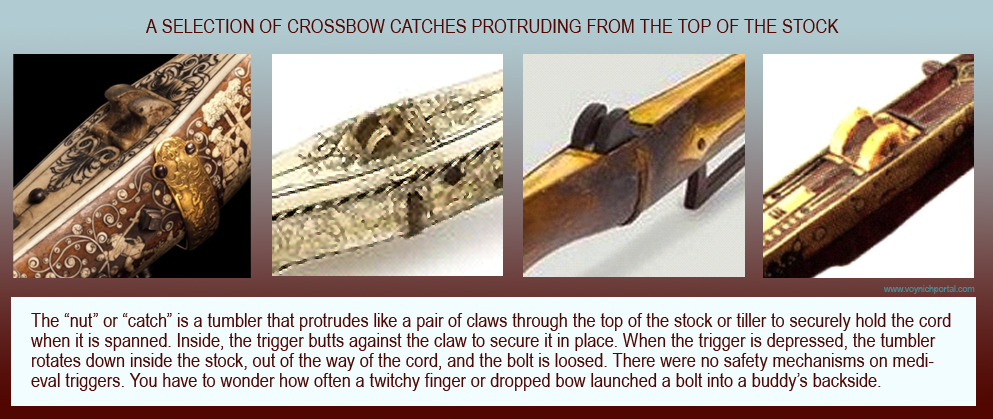

The catch is approximately a third of the way down the stock from the stirrup, depending on the length and style of bow. The trigger “catches” on the underside of the nut so that pulling the trigger moves it just enough for the catch to rotate freely and ZING! the cord is freed and ejects the bolt. Here are some examples of the nut/catch. Notice it is clawlike, to grip the cord securely:

Catches are pretty much alike… or so it seems if you look only at the shape and ignore the mechanics. There’s quite a bit of variation in the distance of the catch from the trigger, and how they connect inside the stock, but there are some things that are necessary for the trigger to work… And this is the important detail that throws all VMS identification efforts out the window… the VMS catch is like the legs on the lobster’s tail in the zodiac roundels, or like the joints in the back legs of the ruminants—it’s in the wrong place.

I looked at the catches of almost 200 historic crossbows, and all of them were located above or slightly ahead of where the trigger attaches to the stock (usually about 1/2″ to 2″, up to a maximum of about 3″). If you look at the VMS drawing again, you’ll see that the catch is about 2″ behind the trigger. This never happens, as far as I can determine. The portion of the trigger inside the stock rotates in a specific way when you squeeze it and the nut has to sit at the right junction to efficiently respond to this movement.

Summary

I would love to say I found bows that closely resemble the VMS bow, and I did have some success, but if this important detail of the crossbow-catch is wrong, maybe others are too.

I would love to say I found bows that closely resemble the VMS bow, and I did have some success, but if this important detail of the crossbow-catch is wrong, maybe others are too.

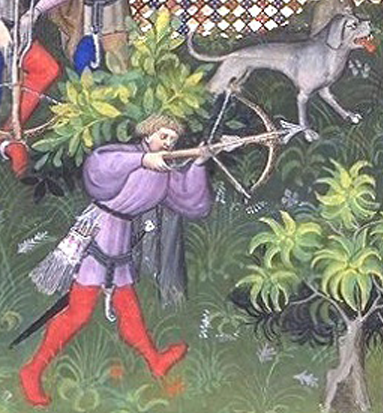

Maybe the tips are artistic, maybe the trigger is lengthened to make it look like it’s touching his hand, not because it’s long, maybe the attachment point of the trigger was moved up to show that it is long… It’s possible the position of the catch is the only thing that’s off, but there’s no way to be sure. We have to look to other factors, like the style of the bowman’s tunic (which is echoed quite well in the hunting scenes of Gaston Phoebus, right) and aspects of the manuscript that seem mostly but not-quite-right.

So, I’ve put crossbow identification on the table for now, but I’ll keep my eyes open for other imagery that might help us understand this roundel, and if I find some, I’ll post it.

J.K. Petersen

© 2017 J.K. Petersen, All Rights Reserved

Thanks for the great post, JKP, looks like a lot of research went into it.

I agree with your conclusion, and this is something I’ve said before in discussions with people who think the image allows for a very specific identification. The illustrator got a crucial part of the crossbow wrong, so we should not rely on its technical details. The thing is a few pen strokes and some of them are demonstrably wrong.

L’image a une époque…. un lieu…. un milieu social… un mystère du voile emprunté!

mais surtout…une AME!

Sa formulation est HÉBRAÏQUE …son contenu!

Mr Bax…la censure de votre part de mes documents explicatifs, me fait sourire….à vous d’en comprendre le pourquoi.

NICOLAS Georges 67ans

JKP

A few comments

First, you have assumed that the image filling the centre of this roundel has as its sole purpose the accurate depiction of a crossbow. I think that you might have explained in more detail what led you to suppose so.

Secondly, you have assumed the maker – working in a circle about 5cm in diameter – would have felt compelled to include every detail of the bow’s construction – and to scale – when working to a length of less than an inch for the crossbow’s stock. Again,. I cannot see why you should suppose the maker had any such intentions. He was drawing a ‘Sagittario’ not a crossbow. In fact, the key to the whole thing is where and when that term was being used for a crossbowman by 1438.

Third, you have failed to offer any coherent account of the archer’s dress. Perhaps you did so in another post. How do you explain the long tail hanging down his back or the obvious impracticality of such wear in the field?

Fourth When you finally turn to the critical matter of roll-locks, you have failed to include the most obvious – that is the earliest-known – example of the type and instead chosen to use examples as much as two centuries too late to be relevant. Omitting the date of their design could be considered merely careless, or actively deceptive. In either case, not a good look for you and a very poor effort if you hoped to assist other researchers.

Fifth, this post (though perhaps not your previous ones) gives a false impression that your effort is the first and only detailed study done. As you should be aware if you’ve done your basic research, Jens Sensfelder wrote his evaluation in the early 2000s, and I wrote a more detailed and complete study for the archer (including his bow) a few years later. My assessment was as a professional iconographic analyst with a background in the archaeology of techologies, but in this case I had the invaluable assistance of a colleague who is a specialist in the archaeology of weaponry. It was he who drew my attention to the Catalan bows found at Padre Island.

Sensfelder is also a specialist – in the history of medieval warfare and weapons.

That my opinion should differ from Senfelder’s is no great thing; nor that you should conclude that you are unable to reach any conclusions at all. What is rather a problem is your failing to provide your readers – some of whom may be better qualified than any of us in iconographic analysis or the history and archaeology of weapons – to read and consider all three of the essays now written about this tiny detail: Sensfelder’s, mine, and now yours.

I certainly intend adding a link to my own paper directing my readers to your later effort as I’ve already linked them to Sensfelder’s earlier ones.

Anyway, best of luck in future.

No, I did not assume that “the image filling the centre of this roundel has as its sole purpose the accurate depiction of a crossbow”. I did some research to see if it was possible for it to represent an accurate crossbow.

Whether the illustrator’s purpose was to create an accurate depiction, I do not know. After looking into it, what I do know is that it is very unlikely to be accurate due to its anomalous placement of one of the key parts.

Diane wrote: “Third, you have failed to offer any coherent account of the archer’s dress. Perhaps you did so in another post. ”

I did account for the dress. I wrote a post specifically on the bowman’s hat and tunic here, and I don’t think the comparison that you posted very recently of the long northern Italian gowns (BL Add 24189) match the bowman’s dress as closely as the examples I posted.

Unlike the VMS, the tunics in your examples have cowls, are gathered rather than pleated, are long, and the sleeve shapes are not as similar. I didn’t just look at tunics, I took the hats into consideration as well (in combination with the tunics in the same illustration if I could find it). I even tried to find examples of bowmen with the right kind of tunic who were drawn with short legs.

Diane wrote: “Fourth When you finally turn to the critical matter of roll-locks, you have failed to include the most obvious – that is the earliest-known – example of the type and instead chosen to use examples as much as two centuries too late to be relevant. Omitting the date of their design could be considered merely careless, or actively deceptive. In either case, not a good look for you and a very poor effort if you hoped to assist other researchers.”

This is nonsense. I did not omit the date of their design. I stated quite clearly at the beginning that actual examples of crossbows from before 1500 are extremely rare. Even those which are thought to MAYBE be from earlier than 1500 are disputed and I thus explained that we have only the drawings to go on to know how they were designed. I did not cherry-pick my pictorial examples and I included dates when they were available. The dates of many crossbows are not known because they were utilitarian items that were constantly repaired with newer parts and thus do not belong to one specific date (I also pointed this out in the article).

I looked for everything and anything I could find that might confirm the anomalous catch on the VMS crossbow but was unable to do so, so there was no deception whatsoever and I don’t know why you are trying to spin it that way simply because we disagree.

Diane wrote: “Fifth, this post (though perhaps not your previous ones) gives a false impression that your effort is the first and only detailed study done.”

I do my research and present it. I haven’t based my findings on anyone else’s research on the VMS crossbow. If I had, I would have said so.

I prefer original sources. If I have a choice between looking at someone else’s research for an hour or looking at actual crossbows for an hour, I will always look at the crossbows and try to make my own observations and conclusions.

Presenting my findings doesn’t mean I’m the only one researching the VMS or the crossbowman. Why would anyone assume that? Voynich researchers are not stupid—the reputable ones are never going to assume (or rely upon) a single source.