Did medieval illustrators confuse Musa (which we now know as banana) with another plant labeled “muse”? Early drawings of “muse” fruits don’t look like bananas. They are small, with pointy ends. In fact, the taste of “muse” was likened to cucumber or melon, fruits that are much more watery than banana. Yet as time went on, the descriptions, drawings, and the name were changed to “Musa”, which we know as banana/plantain plants.

Bananas and other eastern or African semitropical and tropical plants were probably known to Europeans through word-of-mouth, just as they had heard of hyenas but apparently had not seen them. Medieval drawings of hyenas are quite fanciful, and sometimes understood only by their labels. Is this what happened to banana plants? Did they invent the drawings and call them “muse”, or are the early herbals depicting some other plant that became confused with banana plants as knowledge of the banana gradually spread through Europe?

Sugar cane was known in Europe from early times (although it was not imported into northern Europe until later), probably because it’s easier to ship than many kinds of plants, but bananas are not easy to ship. They bruise and ferment and thus were not as familiar to Europeans as sugar cane in the early Middle Ages.

Historical Background

There were a number of plants locally called “muse/musse/mus” in the Middle Ages—field plants like “mouse ear” that are similar to Hieracium, but they don’t look like the 14th-century drawings labeled “muse/musse” in manuscripts such as the Manfredus herbal, or in the various copies of Tacuinum Sanitatis.

So if “muse” is not the mouse-ear plant (which is often included in herbal manuscripts under other names, and usually drawn fairly accurately), and it’s not banana, then what is it?

Lining up the Illustrations

Maybe Egerton 747, the Manfredus du Monte herbal, and versions of Tacuinum Sanitatis can provide clues. There is a plant in the Manfredus manuscript that has an analog in both form and name that might easily be confused with banana.

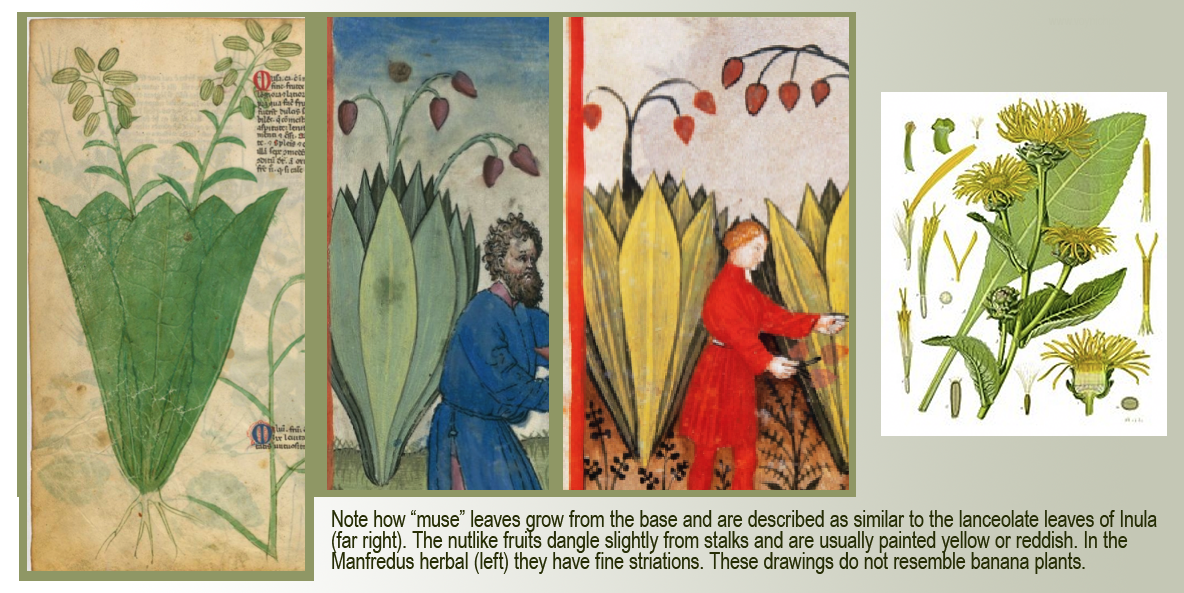

First note how “muse/musse” is drawn. It’s not a good representation of a banana plant. It has a basal whorl of upright lanceolate leaves, similar in shape to Inula, and nut-like dangling fruits sometimes painted red, sometimes yellow (this color difference is significant, as will be illustrated later). Banana plants might look vaguely like this when they first start to sprout, but the stalks grow substantially before they bear fruit and the fruits do not hang on long stalks with skinny petioles above the leaves.

Sometimes the fruits of “muse” are drawn a little more capsule-shaped, with striations, but these too are quite different from banana. The image on the left is from the Manfredus herbal (late 14th century), those in the middle are from two different versions of Tacuinum Sanitatus:

In the text that accompanies earlier drawings of “muse”, the leaves have been compared to Inula (which does not resemble banana leaves), and the taste has been compared to melon and to citric fruits (which doesn’t match well with banana either).

So there are several problems with assuming that “muse” is Musa (banana):

- The name is different.

- The leaves are shaped and positioned differently.

- The fruit stalks are much too tall and the fruits too discrete and the wrong shape for bananas.

- The description of the taste doesn’t fit banana.

In later herbals, the descriptions start to sound more like banana (based on the assumption that “muse” was an alternate spelling for “musa”) and the name is changed to “musa”. Eventually drawings and descriptions of real banana plants are substituted.

Other Possibilities

Is there a plant that matches “muse” better than banana?

Yes. I don’t know if it’s the correct plant, but melegueta matches better to the drawing and description of “muse” than the banana.

And here’s the interesting part (and another reason it might be confused with banana). Banana became known as Musa paradisa. The melegueta plant is known as “pomum paradisi” (apple of paradise). Thus, if someone unfamiliar with melegueta saw the name “muse” in combination with “paradisi” they might assume it was a banana plant.

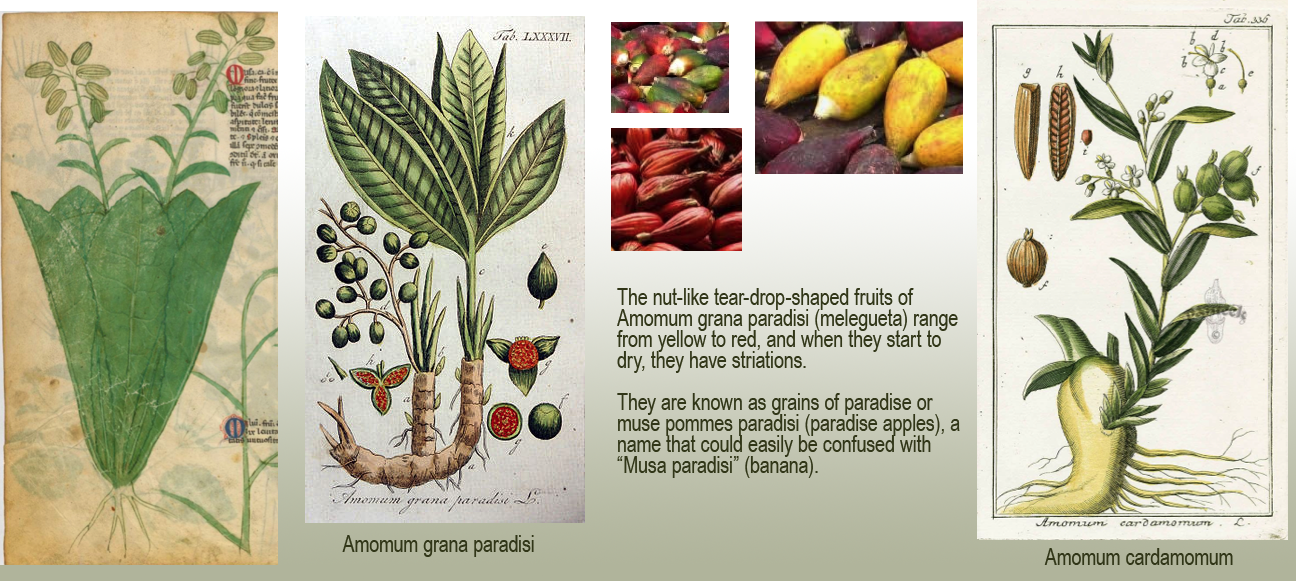

Here are some images of melegueta and cardamom. Melegueta is a west-African plant with lanceolate leaves. It has slightly dangling fruits on spindly stalks, and the ripening fruits are often red or yellow:

Comparison of “muse” plant with leaves and fruits of pomum paradisi, the melegueta plant. Image credits: Bibliothèque Nationale de France, gernot-katzers-spice-pages.com, tropical.theferns.info, sciencedirect.com.

Medieval illustrators aren’t the only ones who appear to have confused “musa” (banana) with early depictions of a plant called “muse”—15th-century annotators and 17th- and 18th-century commentators made the same mistake. No one appears to have critically evaluated the way medieval descriptions and drawings changed over the course of two centuries from “muse” (pomum paradisi) to Musa paradisi (banana), nor have they investigated what exactly was meant by “muse” in the earlier herbals. It has long been assumed that the old herbals, even ones with good illustrations, specifically included erroneous descriptions and bad drawings of banana plants rather than reasonable drawings of a different plant.

The drawing and description of “muse” is similar in shape, proportion, name, and colors to melegueta and a few other Amomum species, but there’s more…

I found two additional pieces of evidence to support this tentative ID.

- The first has to do with taste, which is described in one early medieval source as “citric” (I don’t think anyone would describe the taste of banana as citric). The Wikipedia entry for melegueta describes the taste as peppery “with hints of citrus”.

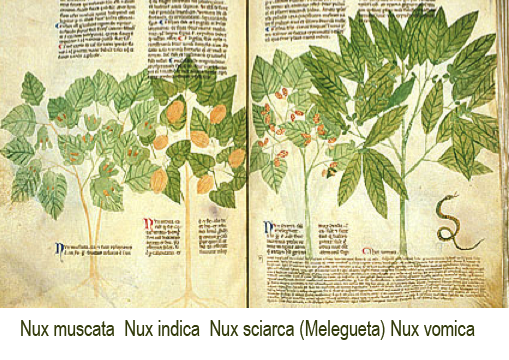

- The second is a sequence of plants in Egerton 747 (c. late 13th century), a reference that bears many similarities to the Manfredus herbal (some say Manfredus is copied from Egerton 747, others say both are copied from a common source). In Egerton 747, is a series of shrubby trees, beginning with Nux muscata and ending with Nux vomica. Note that it includes Nux sciarca (melegueta):

In the Manfredus herbal, the mystery plant “muse” follows “muscata”. If “muse” is meant to represent melegueta, it’s more accurate than the picture of melegueta in Egerton 747, but what is even more significant is that it follows closely to muscata. Manfredus does not correspond 1-to-1 to Egerton plants, but the contents and sequence are very similar.

In the Manfredus herbal, the mystery plant “muse” follows “muscata”. If “muse” is meant to represent melegueta, it’s more accurate than the picture of melegueta in Egerton 747, but what is even more significant is that it follows closely to muscata. Manfredus does not correspond 1-to-1 to Egerton plants, but the contents and sequence are very similar.

Melegueta (Aframomum grana-paradisi) is a medicinal plant in the ginger family with anti-inflammatory properties. It is native to coastal west Africa, and is related to cardamom. Its inclusion in Egerton 747 suggests that it was known in Europe at least since the late 13th century (possibly through Arab traders).

There are several Amomum plants that should be considered together with melegueta, including Amomum villosum, Amomum cardamom, and Amomum compactum (false cardamom).

Note that the Manfredus and Tacuinum drawings of “muse” resemble Amomum plants more closely when they are younger. Melegueta leaves tend to become more palm-like as the plant grows, although some of the other Amomum species remain more lanceolate, like the drawings above.

Summary

I’m not sure how a name like Nux melegueta or Amomum might become “muse”*, but it’s not surprising that “muse” (pomum paradisi) might be confused with “musa paradisi” (banana).

Name changes are not uncommon. “Earth apple” used to refer to Cyclamen, a common medicinal plant with a big lump of a root. After the conquest of America and import of New World plants into Europe, the potato came to be known as the “earth apple” (pomme de terre) and Cyclamen gradually lost the name.

But I don’t think this is a case of the name changing. I think it’s the result of confusion…

Aframomum and Musa (banana) plants were not well-known in the west and had similar names (pomum paradisi vs. musa paradisi).

The 13th- and 14th-century drawings and descriptions of “muse” match well to melegueta and a few of the other Amomum species, and less well to banana. By the middle of the 15th century, traditional descriptions were altered to better fit the banana and the name was changed to “musa” and, finally, by the 16th century, the name “musa” was paired with drawings of actual banana plants and the name “muse” seems to have disappeared.

J.K. Petersen

© Copyright 2018 J.K. Petersen, All Rights Reserved

Postscript, Nov. 10, 2018: One possible origin of the plant name “muse” that I forgot to include is hinted at in this quotation from classical Greek, which connects the Muses with a plant called “amomum” as follows:

“… Then he wove in Damagetus (a dark violet); Callimachus’ myrtle—sweet, but ever full of sour honey—; Euphorion’s rose campion; and the Muses’ amomum, who takes his name from the Dioscuri.”

It’s not enough information to identify the plant (Fée suggested Amomum racemosum, but there is no consensus of opinion) or to know if a connection between the muses and something called “amomum” still existed in the Middle Ages, but it might be worth filing for future study.

*Perhaps the answer is closer to the home of the plant itself. The Timneh tribes of Sierra Leone generally refer to the amoma/melegueta plants as “massa” (The Pharmaceutical Journal and Transactions, Volume 16, J. & A. Churchill., 1857. See also detailed discussion in Elements of Materia Medica).

Forgive me but the aim of this post seems to be to find ways to avoid the consequences of the image’s identification (by Edith Sherwood) and the conclusion I reached and explained in a very detailed and throughly documented analysis of the image. Since this identification has stood, unchallenged, for years and was one of the few which were not challenged, I think your efforts to discard it need as much explanation as would any effort to discard the ‘Viola’ identification. That is, you need to address the primary document and show where the detailed analysis of both stylistics and content is, in your opinion, in error.

If the aim of studying this manuscript is to understand the manuscript, then of course no-one wants to get this, or any other item, wrong. But one needs evidence of just which parts of the detailed commentary are wrong in your opinion, not just the urging of some ‘alternative’.

If, on the other hand your aim is to get rid of an item which opposes your preferred hypothesis for the manuscript, then of course you might want to substitute for an existing piece of evidence, some other idea more consonant with your desired outcome.

I understand how frustrating the manuscript can be – and how tempting to ignore or dismiss or replace bits that won’t fit. But doing so doesn’t serve the manuscript’s study in my opinion, so I myself decided not to form ‘theories’ at all; just to do my job and evaluate the imagery, leaving conclusions to Waaaay last.

When I consider what you have adduced by way of evidence, I cannot see any similarity to the primary document in the pictures you present. Not in terms of stylistics, nor proportions, nor details nor anything else.

Now, it is true that many of the botanical images make use of visual ‘shorthand’. I’m not speaking of the root-mnemonics but of representation of parts (often the flowers) by employing a conventional form which was well known and bore cultural significance for the people among whom the picture was first enunciated. Since those conventions – which I identified and illustrated, explaining the reason and widespread use for these forms – are not native to the Mediterranean, much less Latin Europe I could understand if the banana-group picture had been one of those sort. It is, however, one of the most nearly literal images in the entire manuscript, including perfect representation of the root – never seen in wholly western imagery for more than a century later.

In short, I stand by my evaluation of that image, and its proofs. The implication for one or another theoretical history for the manuscript is not really my problem. It just means the work isn’t a Latin herbal or anything like it.

Perhaps you won’t want to publish this comment, but as a professional in my field I feel offended to have a formal evaluation treated as if it were a bit of guess-work. Informed debate yes, but that’s not what you’ve put up here.

D.N. O’Donovan wrote: “Perhaps you won’t want to publish this comment, but as a professional in my field I feel offended to have a formal evaluation treated as if it were a bit of guess-work. Informed debate yes, but that’s not what you’ve put up here.”

This blog has nothing to do with you, Diane, or anything you have written about banana plants. It doesn’t even mention the Voynich Manuscript.

I have been interested in plants all my life and I spend hours studying medieval herbals (both drawings and text) and I have been wanting to locate the source of the plant “musse/muse” since 2009, long before I made your acquaintance. I have found quite a bit of evidence that the plant called “musse/muse” in the early botanical manuscripts is not a banana/plantain plant, nor one of the “mouse-ear” plants.

In fact, I found more information today that adds to the evidence that “musse/muse” in the early herbals is not Musa (plantain/banana).

There is a 12th century medicinal manuscript that lists the plant “muse” in the section of plants that are used for their seeds and their leaves. In contrast, banana seeds and leaves were not harvested for medicinal use in the west in the Middle Ages. In fact, banana seeds are usually eaten along with the fruit, not separated out. Meleguete and various Amomum plants are specifically used for their seeds and sometimes for their leaves as well. In addition to the fact that the natives called these plants “massa”, and that Egerton 747 includes meleguete in almost the same position as “musse” in the Manfredus herbal, the evidence is accumulating that the early drawings labeled “musse/muse” represent one of the plants of the Zingiberaceae family.