“…some symbols in the Voynich Codex show similarities to letters found in sixteenth century codices from New Spain (Tucker and Talbert 2013; Comegys 2013) particularly the Codex Osuna (Valderrama 1600; Chávez Orozco 1947).” —Janick and Tucker, Aug. 2018

The authors are talking about shapes that roughly resemble EVA-k and EVA-t. The following statement is much more surprising:

“We thus conclude that the author of the Voynich Codex made up his syllabary/alphabet, and the letters were borrowed from contemporary post-Conquest MesoAmerican manuscripts such as the Codex Osuma.”

In scholarly circles, “conclude” is a strong word—a word that needs to be backed up with solid evidence. Unfortunately, I find this conclusion highly questionable. The examples the authors use in their arguments are conventions that originated in Old World Latin scripts long before the 16th century. How can one use Old World scribal conventions to argue for a New World conclusion?

Is There a Preponderance of Evidence to Support the Conclusion?

Perhaps the authors felt that if the glyph shapes are taken together with botanical and biological identifications, there is enough evidence to support a New World origin, but the botanical and biological identifications of Tucker, Talbert, Janick, and Flaherty are highly questionable, as well. If you haven’t been following this discussion, then at least scan-read the previous blogs:

- Mistaken botanical and biological identifications?

- Is it a sunflower, or could it be something else?

Even though the VMS 93r “sunflower” has a number of possible identifications (both New and Old World), Janick bases broad conclusions on this unproven ID as though it were fact:

“Simply put, there is no way a manuscript written on vellum that contains a sunflower and an armadillo could have been written before 1492,” —quoted on Purdue The Exponent news site, 10 Sep. 2018

There isn’t any proof of the identity of the “armadillo” either. It looks more like an Old World pangolin than a New World armadillo, but even this identification can be contested.

What I see in the papers and book by these authors is a collection of inadequately researched suppositions combined in a circular argument to support a New World theory. They pick out a few similarities and ignore the larger body of contrary evidence. They identify two completely different fish as the same fish. One of the plants they identified doesn’t even grow in MesoAmerica. They ignore numerous significant details like the cloudband under the “armadillo”. They ignore alternate IDs for the sunflower.

Unfortunately, the authors’ identification of Voynich-like glyphs suffers the same lack of critical evaluation as the plant and animal IDs, so let’s take a closer look at those.

The VMS-like Letters in the Codex Osuna

Here are examples of the Voynich-like glyphs cited by Janick and Tucker (and by Tucker and Talbert in a previous publication) in the Codex Osuna.

EVA-k is at the top, and EVA-t is at the bottom. Note that the handwriting is different:

Before you say, “Oh, those are similar”, make sure you read the rest of this blog. Bats and owls might look similar to a visitor from another planet, but one is a mammal, the other is a bird, and they are not closely related.

Ivatsevichy Visual Similarity is Not Enough (especially when they’re not actually that similar)

Something important Janick and Tucker did not mention is that the letters that appear to resemble EVA-k and EVA-t exist in two different scripts in two different languages. Failing to mention this distinction obscures the origin of these shapes, so I will fill in the missing pieces:

- The EVA-k shape is in the sections written in Nahuatl.

- The EVA-t shape is in the sections written in Spanish.

There are simple reasons for this, but they are important ones because there is no specific relationship between the Spanish and Nahuatl shapes. The similarities are coincidental, but some background might be necessary to make this clear…

cheap modafinil australia Nahuatl Version of EVA-k

If you’ve heard the Bushmen click language, you know it can be very difficult to express this with Latin letters.

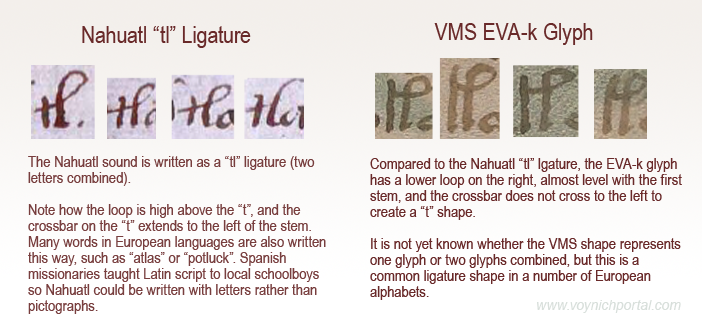

Similarly, there is a sound in Nahuatl that is hard to write. It’s made with the tongue against the back of the teeth, so the Spanish missionaries chose to represent the sound as the letters t + l and they wrote it as a ligature tl, with the crossbar of the “t” connecting to the loop of the “l”.

This ligature is not specific to Nahuatl or to the New World. It exists in Old World words like “atlas”, “battle”, “gatling”, etc. Note that the crossbar in the first letter “t” always extends some distance to the left of the stem, which is different from the way EVA-k is written:

It’s possible EVA-k is a ligature (two shapes combined) but if it is, then it follows age-old scribal conventions that are not specific to the New World (or to Nahuatl script). It doesn’t seem likely that VMS EVA-k was copied directly from Nahuatl if one goes by shape alone. It is more similar to some of the European ligatures and abbreviations such as “Il” (French) or “Item” (Italian, German, Latin) than the ligature on the left.

What About EVA-t?

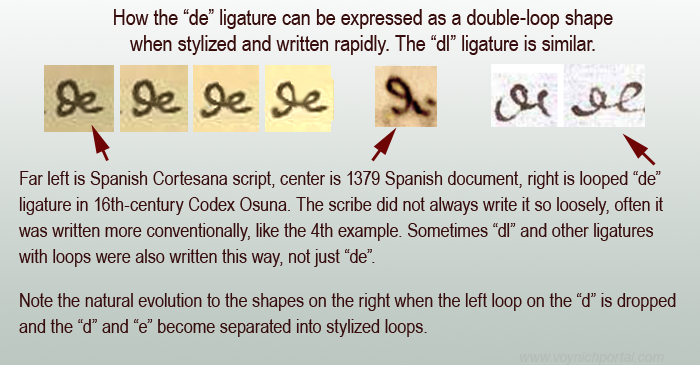

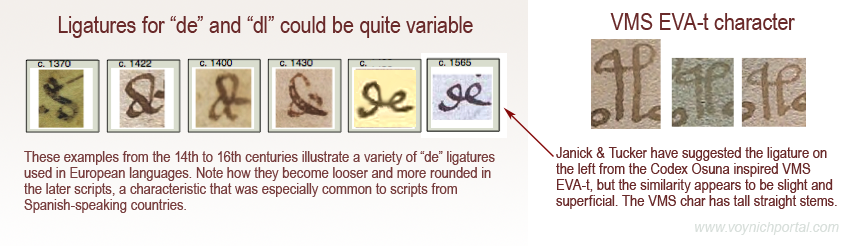

Another common ligature in Old World languages that used Latin characters was the d” + “e” and since the letter “d” was written a dozen different ways, the “de” ligature is quite variable. A similar ligature combines “d” and “l” as in words like “headless”. Sometimes they are hard to tell apart from each other and from ligatures like “il”, but the concept is the same—two letters are combined so they can be written faster or in less space.

Here are examples of how “de” and related ligatures were sometimes written in Spanish scripts from the 14th to 16th centuries. The two on the right are from the Codex Osuna. The faster and loopier the writing, the more it resembles EVA-t (sort of):

The examples on the right illustrate how loose a ligature could be and how combinations like “de” or “dl” or “Il” or “Ie” need to be seen in context to be distinguished from one another, especially if it is an open-loop “d” followed by a very round “e” or “l”.

The examples on the right illustrate how loose a ligature could be and how combinations like “de” or “dl” or “Il” or “Ie” need to be seen in context to be distinguished from one another, especially if it is an open-loop “d” followed by a very round “e” or “l”.

It has been suggested by Janick and Tucker that the glyphs above-right inspired EVA-t in the VMS, but this seems unlikely. EVA-t has long straight stems:

It’s possible the VMS char is a ligature, but even if it was inspired by “de” (I highly doubt that “de” was the inspiration but let’s pretend for a moment that it was), this ligature was common in many Old World languages.

The authors of Unraveling the Voynich Codex didn’t mention that the two shapes that resemble VMS glyphs are taken from two different sets of scripts (one in Nahuatl, the other in Spanish) and, more importantly, that these shapes were part of the normal scribal repertoire of Old World Europe and thus might have been seen by the creator of the Voynich Manuscript long before the conquest of MesoAmerica.

Summary

The authors didn’t provide any solid evidence that the inspiration for these shapes was specifically New World sources. In fact, the position of EVA-k and EVA-t within VMS tokens doesn’t match well to Nahuatl letter order, either, which further weakens the authors’ interpretation of the VMS script as a Nahuatl substitution code.

I’m not entirely opposed to New World interpretations. I think the VMS is probably Old World, but I will listen to New World arguments, as long as they are good ones. Unfortunately, many New World theories are marred by faulty logic and hasty conclusions.

J.K. Petersen

© 2018 J.K. Petersen, All Rights Reserved

I have to agree with the authors that

“Simply put, there is no way a manuscript written on vellum that contains a sunflower and an armadillo could have been written before 1492,”

and since our best information is that the vellum was made between 1400-1438, then it follows that persons who imagine they see in the drawings and armadillo or a sunflower are – simply put – wrong.

This is because no one could possibly write on an old piece of vellum? The word palimpsest doesn’t exist, and Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address is a fraud because it could not possibly have been written on the back of an old envelope? Bye the way, in another matter, D. O. thank you for pointing out earlier references to and support for the Mesoamerican Hypothesis that those of Tucker et alia including your own and that of the Comegys twins.

JK: I enjoyed the precision and logic of your article and found it refreshing. However, you cite my work and lump it together with the logic of professors Janick and Tucker. Please don’t.

I agree that the paleography of Janick and Tucker is inadequately researched and their reasoning circular. They do not, as do you and I, base their opinion of the sound values of the Voynich letters on the scholarly opinion of paleographers and experts.

You examined their citation that examples of the Voynich letters EVA T and may be found in the Codex Osuna. Like you I was unable to find the form of the EVA t in any of their cited sources. You may find a good clear example of EVA t on page 74 in appendix IV-3 to my monograph Voynich Manuscript: Aztec Herbal from New Spain on my website http://voynichms.com or posted on academia.edu. It is transcribed by the author as ‘tl’ and is found in the Codice Santo Toribio Xicotzinco Documento A. I cite Meade de Angulo, Mercedes (1985) Dos códices del pueblo de Santo Toribio de Xictotzingo, Tlaxcala. Universidad Autónoma de Tlaxcala, México, but the illustration and transcription may also be found in La Escritura Pictografica en Tlaxcala by Luis Reyes Garcia (1993) I have seen that work in its entirety on the web but not lately. A less clear example may be found in one of the documents associated with the Codex Aubin, but not in the Codex Aubin per se.

A good clear example of EVA k may be found in first line of the second folio of the Codice de Otlazpan. It is used in the name Otlazpan spelled ‘Otlazpa’. Leander, Birgitta. (1967). Códice de Otlazpan: Acompañado de un Facsímile del Códice. [Codex of Otlazpan: Accompanied by a Facsimile of the Codex] Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia: México, D. F. Unfortunately, I did not include that in my appendix and I have not found a good online source.

You mentioned that the tl does not match well with Nahuatl word order. If by that you mean that there are more tl’s on the left margin than right, then perhaps, as my brother James Comegys suggested back in 2001 and earlier, this means the manuscript is better read from left to right.

You are quite right that the example of EVA t cited by Janick and Tucker is transcribed ‘de’. I told them so and they cite my work, but not the correct location of EVA t. They then go on to strongly disagree with the work of my brother who is trained in linguistics and who like them offers a partial translation, but no precise historical evidence.

In part I did the research to find historical evidence of the alphabet in order to prove or disprove my brothers earlier work. I do support the general thesis that the Voynich Manuscript has a Mesoamerican provenance based on the MesoAmerican art style and content, and the alphabet.

The circularity of reasoning you cite may, I believe, be avoided by starting with the historically cited sound values of the Voynich letters. I do not subscribe to the methodology of Janick, Tucker, or necessarily to that of James Comegys in the matter of the historically attested sound values of the Voynich Manuscript or their translations.

Like you I think that clear proof of the content and provenance of the Voynich Manuscript must await a clear translation. Frances Berdan told me that the provenance of a document cannot be certain until it can be read.

I have not yet published or offered any translations, although I am working on another article to explain the alphabet and a partial translation based on historically atested Voynich will be part of it.

If you will send me your email I will be happy to scan a picture of any of the letters you mentioned.

Thank you for your clear thinking.

John Comegys

Above I mistakenly said that the tl’s on the left suggest the reading direction is left to right. This is an error. Tl is a very common noun ending in Nahuatl, and since there are about twice as many tl’s on the left as on the right that suggests that the reading direction is reversed, that is right to left, as in Arabic or Hebrew. I checked this against a sample Nahuatl text and found the preponderance of tl’s were at the end or the words aand when written left to right are on the right. Since the number of tl’s is greater on the left in the Voynich Manuscript this suggests the reading direction is reversed.

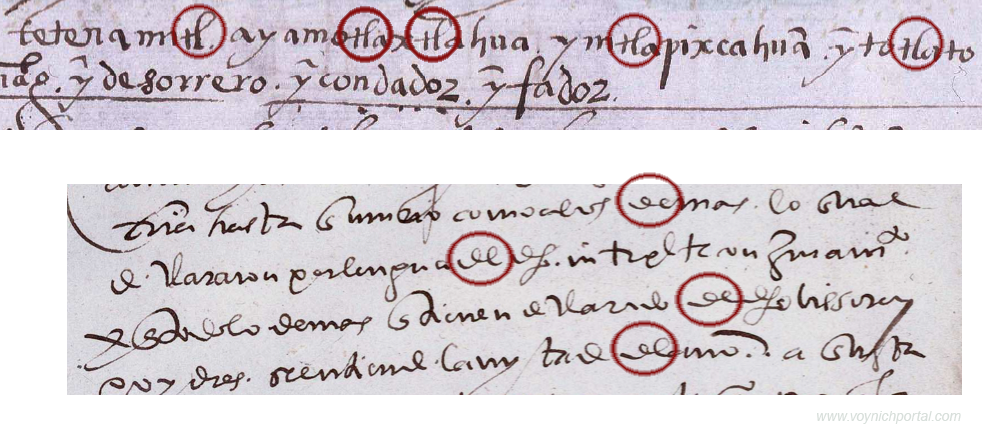

Transcription of the Codex Osuna by Dr. Cortes Alonso. Figures claimed by Tucker, Talbert and Janick to be examples of EVA k sounding tl are underlined following illustrations posted by J. K. Petersen on Voynich Portal in his posting entitled The Ligature legacy.

Folio 7-469r Line 2

2) tetnamitl ayamo tlaxtlahua yn itlapixcahuan yn totlatocauh yn su

3) mag(estad) yn desorrero yn dondador yn fador

The first sample, taken from a sample of Nahuatl text clearly demonstrates that EVA k is transcribed as tl. [Spanish loan words are in the text, for example mag. for magestad – majesty, desorrero for el tesorero — the treasurer, and fador for factor.]

Note the EVA v above the ‘y’s acts as a tilde and thus replaces the n in yn the nahuatl demonstrative usually translated as ‘the’. Note the EVA a’s transcribed as ‘a’. Note the EVA d or perhaps EVA j transcribed as ‘s; in desorrerro.

3) tierra hasta que murió, como a los demás lo qual

4) declaron por lengua del dicho intérpete con juramento,

5) y en todo lo demás que tienen declarado del dicho vissorey

6) e oydores, se entiende la mitad del año a questa-

“Codex Osuna” folio 7-469 recto Lines 3 and 4, and folio 25-487 Lines 3 through 6, inclusive as transcribed by Vicenta Cortes Alonso in Pintura del Gobernador, Alcaldes y Regidores de México Estudio y Transcripción, Ministerio de Educación y Ciencia, Dirección General de Archivos y Bibliotecas (1976) [pages are not numbered]