After collecting more than 500 zodiac series and analyzing their patterns, it becomes apparent that the VMS zodiac figures are consistent with thematic traditions from central Europe ranging from the late 12th century to the early 15th century.

Discovering this goes far beyond comparing images. Traditions and thematic families allow leeway for personal expression. For example, colors or the direction in which an animal is facing were not always slavishly copied by illustrators and do not appear to negate a thematic relationship to other zodiacs. Considerable study was necessary to determine which details are significant and what can be expected to vary within a reasonable range without straying outside the pattern.

The VMS only includes 10 of the 12 figures that are traditionally found in figurative representations of “zodiacs”, symbols of constellations that occur along the ecliptic, so Aquarius (water bearer) and Capricorn (the goat) were excluded from searches.

The Difference Between Classical Zodiacs and A Subset of Medieval Zodiacs

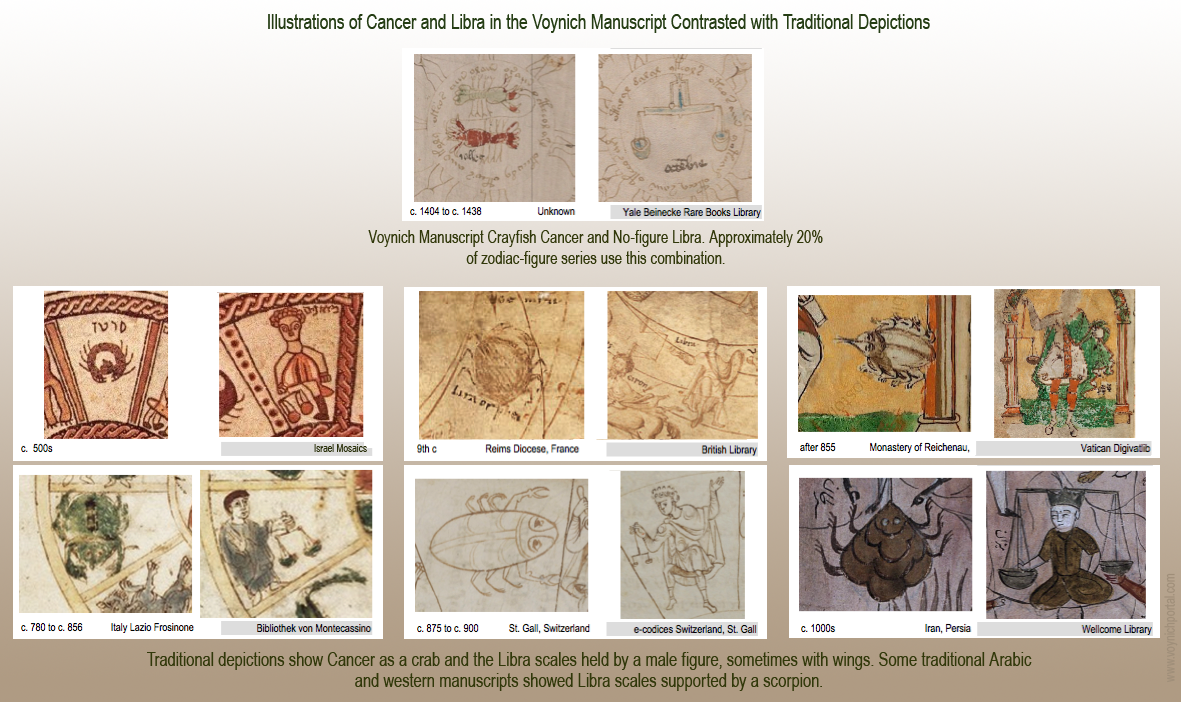

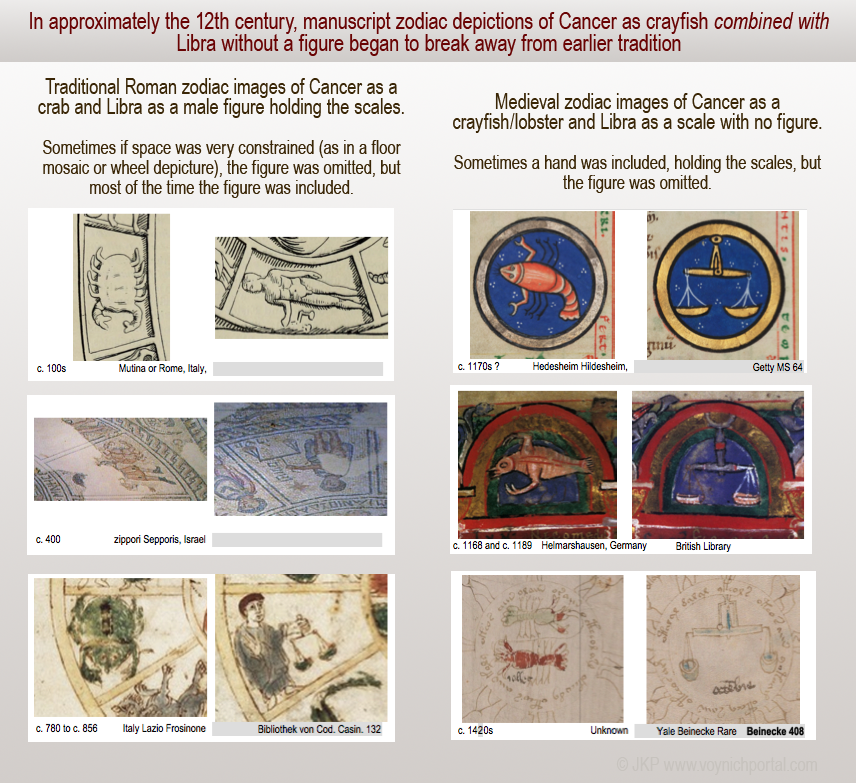

Classical drawings of zodiac figures depict Cancer as a crab and Libra as a figure holding the scales or sitting on top of the scales. Most of the Roman carvings, and the Beit Alpha mosaics, follow this model, as do 11th- and 12-century friezes in Spain and France. Here are some early examples that illustrate how the VMS departs from classical tradition by using a crayfish instead of a crab and a scale with no figure:

Occasionally, when space was constrained, the Libra scales were drawn without a figure, but those in manuscripts were usually held by a male figure, or by a scorpion. Similarly, Virgo was usually male. Virgo and/or Libra were sometimes drawn with wings. As time went on, a female was gradually substituted for the male and wings were less often included.

Patterns that Relate to the VMS

I have already posted some “combination searches” in previous blogs. This one attempts to zero in on which relationships to other manuscripts are the most crucial.

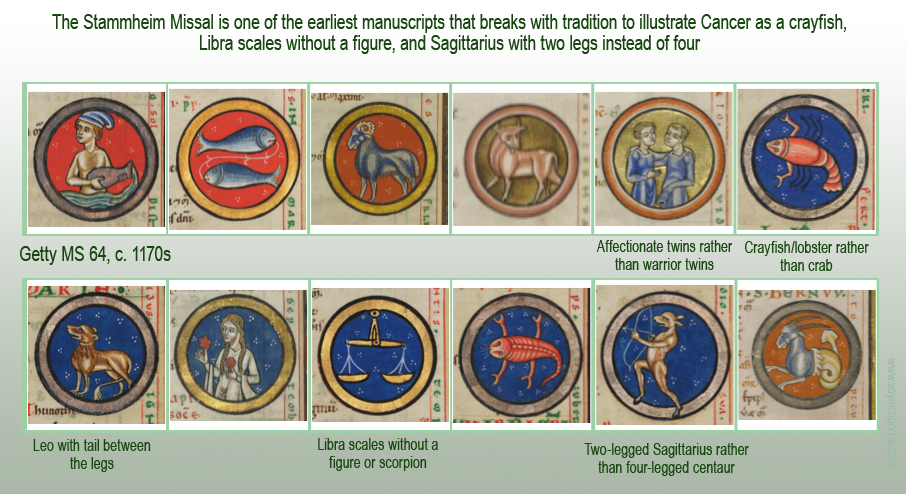

Using a sample of 520 medieval zodiac series, only 25% were found to depict Cancer as a crayfish/lobster together with Libra scales without a figure. This break with tradition may have originated in church portal sculpture, but appears to have entered manuscripts sometime around the 12th century:

This puts the VMS in the thematic minority. If we filter the zodiacs further, to exclude Sagittarius with four legs, it reduces the number to 6%.

What is particularly interesting is that this added filter does not change the approximate date range of early examples that break with tradition in the same ways as the VMS and, as an added bonus, the following 12th-century examples also include Leo with his tail wound between his legs. When a pattern like this occurs naturally, without explicit filtering, it is usually not a coincidence:

Some of the zodiacs from this time period match the first three filters, but continue to use the traditional 4-legged centaur to represent Sagittarius. Those with a centaur have proportionately fewer Leos with the tail between the legs. Even though the two sets are regionally similar (primarily Germany and, to some extent France), this may be the beginning of two separate branches.

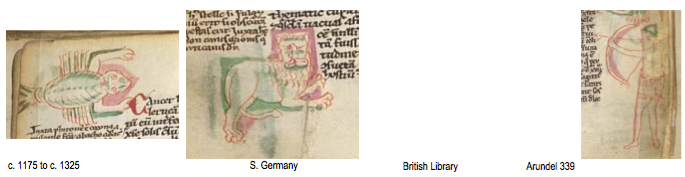

This series from southern Germany is incomplete (Libra is missing) but it shows that even zodiacs that are drawn quite differently can follow the same thematic patterns:

Note that by the 14th century, leg-tail Leo was paired with centaur-Sagittarius more often than in earlier manuscripts. Traditions don’t always diverge, sometimes they go the other way, as well.

ordering Aurogra online When did Cancer as a crayfish emerge?

Some might say Cotton MS Galba A XVIII (9th c) is the first crayfish, but it’s very oddly drawn, with two heads, and it was very rare for English manuscripts to include a crayfish, most of them are crabs. It is possible that it’s not from England (historians aren’t sure). Many manuscripts in English collections are thought to be from Normandy.

Badly drawn crabs sometimes look like crayfish, but one of the earliest unambiguous crayfish is in Vatican Reg.lat.123 from St. Maria Rivipulli/Ripoll monastery, Catalonia, Spain (mid-11th century).

Crayfish were historically abundant in this area and are still featured on many menus, so perhaps that’s why they substituted a crayfish for a crab. However, as can be seen from the image above, the rest of the zodiac series is completely traditional, and the scales are carried by a winged figure. Other than the crayfish, it doesn’t resemble the VMS.

Taking Cancer and Libra Together

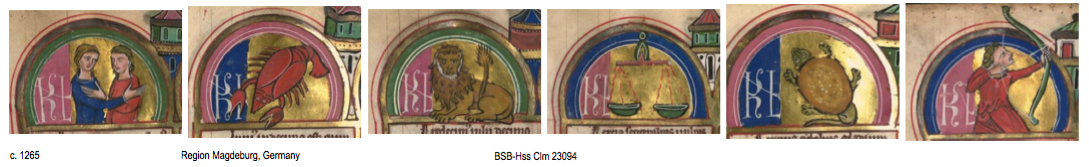

One of the earliest examples that includes both crayfish-Cancer and no-figure Libra is the Stammheim Missal, originating in Hildesheim, Germany, c. 1170s. I have mentioned this before because it has other commonalities with the VMS (including two-legged Sagittarius, and Leo with the tail through the legs). It doesn’t match on all counts, but it’s one of the earliest manuscripts that hints at the transition to VMS-like zodiacs,. Note that the figures are contained within roundels:

There is a Psalter fragment in the British Library (Landsowne 381) created around the same time as the Stammheim Missal that has similar Cancer, Libra, and leg-tail Leo, but the twins are dressed in Roman garb and are not touching, and Sagittarius is a four-legged centaur.

There is a Psalter fragment in the British Library (Landsowne 381) created around the same time as the Stammheim Missal that has similar Cancer, Libra, and leg-tail Leo, but the twins are dressed in Roman garb and are not touching, and Sagittarius is a four-legged centaur.

What about Gemini?

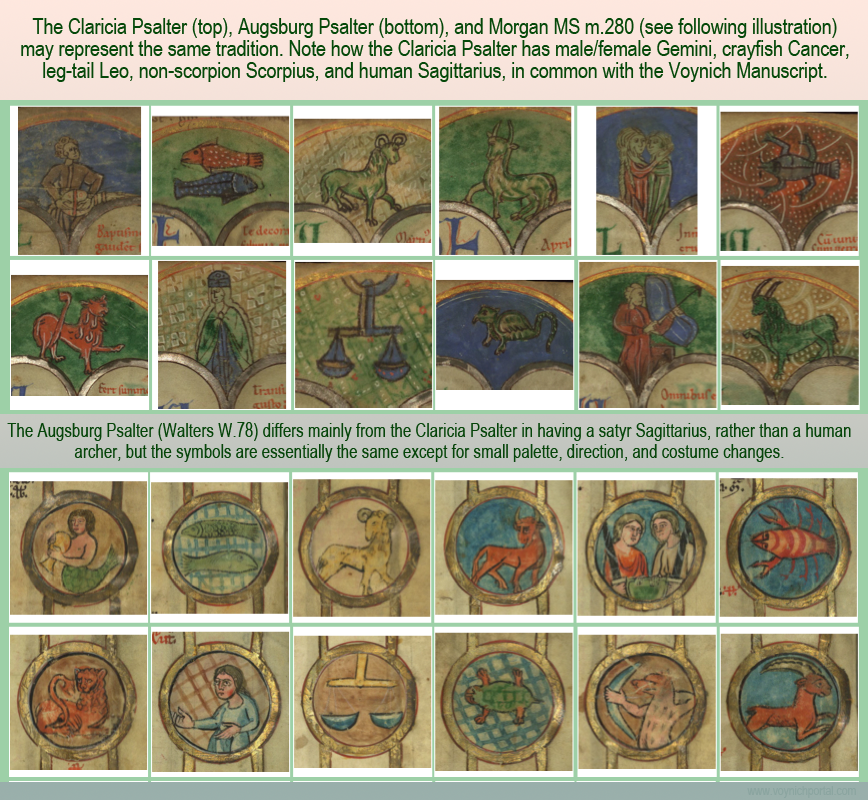

I’ve mentioned the Claricia Psalter numerous times because it has much in common with the VMS. In addition to crayfish Cancer and no-figure Libra, it has a leg-tail lion, one of the first overtly affectionate male-female Geminis, a human Sagittarius, and a non-scorpion Scorpius. It originated in Augsburg, Germany, in the 12th or 13th century. In terms of the basic “template”, it differs very little from the VMS and is clearly modeled on the same themes as the Augsburg Psalter. I’ll repost the images:

Note how the goat and the ram are painted different colors, the turtle/tarasque is from a different angle, and the bull and goat are facing the other way, and yet the overall thematic similarities are striking.

Augsburg is in southern Germany, not far from where Hildegard von Bingen created these zodiac figures:

Hildegard von Bingen’s zodiac series (c. 1200) features crayfish-Cancer, no-figure Libra, and non-scorpion Scorpius, but Sagittarius is a traditional centaur, and Leo’s tail does not thread through the legs, which makes it more similar to the Oettingen Psalter (BVB Cod.I.2.4.19) and the Bambergher Psalter than the VMS.

You may have noticed that the Soissons Cathedral windows are quite similar to the VMS and even include trees in the background, but some of the glass has been replaced and it’s difficult to know if the new glass mimicked designs from the 12th century or updated them. If the designs are faithful to the original, they follow a similar model to the VMS, including leg-tail Leo and two-legged Sagittarius, as discussed in my earlier posts on the evolution of zodiacs. It even looks like Aries might be nibbling from a bush or a basket.

You may have noticed that the Soissons Cathedral windows are quite similar to the VMS and even include trees in the background, but some of the glass has been replaced and it’s difficult to know if the new glass mimicked designs from the 12th century or updated them. If the designs are faithful to the original, they follow a similar model to the VMS, including leg-tail Leo and two-legged Sagittarius, as discussed in my earlier posts on the evolution of zodiacs. It even looks like Aries might be nibbling from a bush or a basket.

The use of a crossbow rather than a longbow probably represents a sub-branch or may, in some cases, be a simple matter of illustrator choice (crossbow tournaments were popular at the time). The most important distinction for this sign appears to be the number of legs rather than the kind of bow. Whether Sagittarius is human or satyr also appears to be less important than the number of legs.

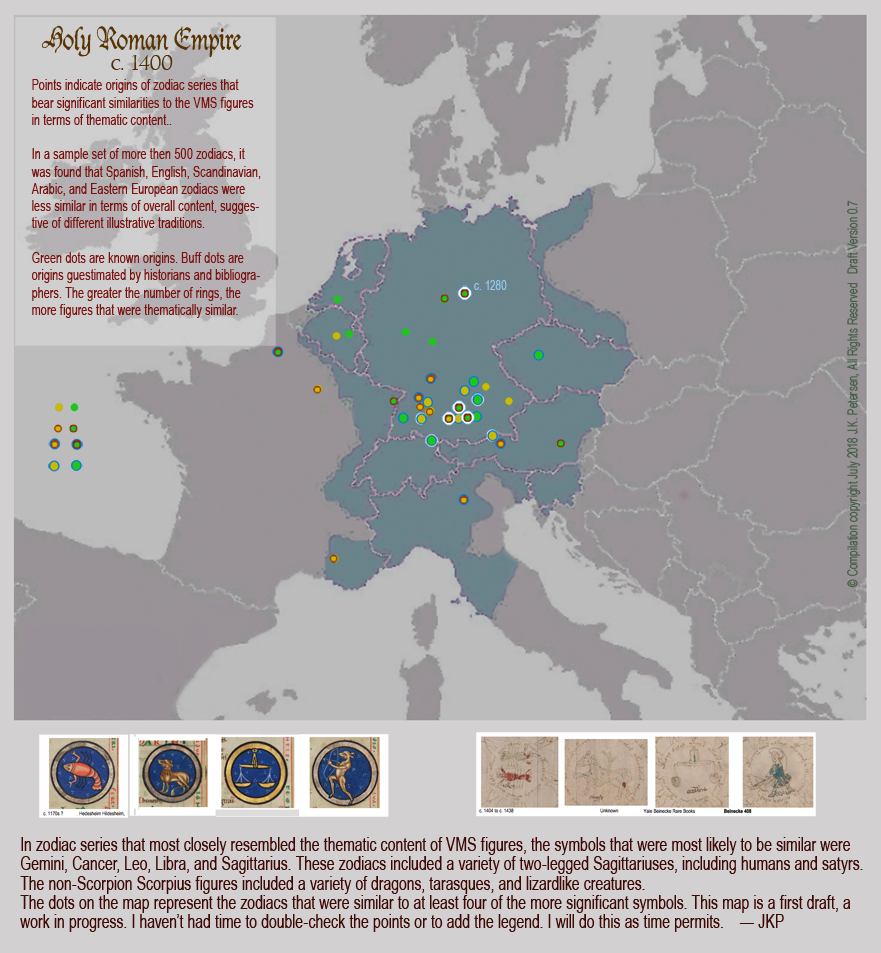

The Origins of the Traditions

I’ve created a map to show the origins of manuscripts that emerged with these filters. This is a work in progress and I have not yet double-checked the datapoints, but they are accurate enough to show that zodiacs, when filtered for Crayfish-Cancer, no-figure Libra, 2-leg Sagittarius, and leg-tail Leo, are conspicuously clustered within the Holy Roman Empire and very conspicuously absent from England, Scandinavia, Spain, southern Italy, southeast Europe and the Middle East (at least so far).

Summary

I’ve mentioned these zodiacs in previous articles and can’t present all the pictures because there are too many for one blog, but I did want to emphasize this: the data tells us that the VMS fits comfortably within existing traditions, particularly those in Germany and northeastern France and Flanders.

This doesn’t reveal where the creators of the VMS were from, but it does suggest that at least one of them was familiar with specific illustrative themes and probably copied the ideas (not necessarily the drawings) from one or more zodiac-series exemplars that originated between c.1170 to c.1430. Some of the English zodiacs are similar, but they differ from the VMS in favoring a centaur-Sagittarius, and Gemini as nude male twins.

If you filter even further to include affectionate Gemini and non-scorpion Scorpio, north-central Germany comes closer than England or France:

Examples from 13th-century Augsburg and Magdeburg/Hildesheim are particularly significant. In fact, these somewhat distant locations might indicate an important line of transmission between north and south.

J.K. Petersen

© Copyright 2018 J.K. Petersen, All Rights Reserved

IIRC, Soissons was severely sacked in the early 1400s in the Burgundian – Armagnac conflict. So the cathedral windows may well be roughly contemporary to the VMS parchment dates or a bit later.

JKP –

Although Koen’s research has done a lot to point us in the right direction in the work of provenancing the calendar’s central emblems, (just as the earlier work done by Marco Ponzi and Darren Worley began it in earnest), it is still a little soon to announce as if settled the many outstanding questions raised by the Voynich calendar diagrams, and it cannot be done by referring to some among the central details without reference to the whole series and the diagrams as a whole.

Since interpretation of the central emblems as a zodiac is more justified by longstanding habit than by what is actually in the manuscript, I feel that any final provenance must explain the ways in which the series differs – as it plainly does – from any known zodiac in the Latin manuscript tradition.

About picturing a ‘lobster’ [the usual practice in art history today is increasingly to call it a crayfish] – I have no wish to pre-empt Koen’s ongoing and meticulous study, but I think I may say that my understanding is that it is believed to derive from an early copy of the Germanicus Aratos, and it appears most often within the lines of Anglo-French-Norman Sicilian communication, though less in England than in France and Sicily – and also in Spain; it becomes more popular over time, and it is also evident that there’s a conscious effort made as the form is more widely adopted, of seeing Cancer as Sorpius’ counterpart: a ‘sea-scorpion’ to the land-scorpion. This I attribute to a classical Latin usage – not common, but found in influential writings such as Cicero’s – whereby the word ‘nepa’ might mean either a crab or a lobster/crayfish (as Koen says, the morphology is not greatly different).

re ‘nepa’ vide Isidore’s Glossary.

A lovely, late-fifteenth century expression of that intention to make Cancer and Scorpius a ‘pair’ is found in the French-made Book of Hours (Roman rite) for Rene of Anjou.

Koen ongoing work at present suggests the form’s popularity derives from that of the genre of ‘Marvels-rerum-naturis’ literature; the first flowering of which occurs , as I’m sure you know, in Paris with the ‘de rerum naturis’ of Thomas of Cantimpre. But that is ongoing research, and not my research, so I’ll stop – but first I’d like to ask for details of those scholars whose opinions you mention in your post.

PS – I think it fine of you to permit critiques of your posts; some prefer to convey an air that their ‘take’ is beyond debate.

D. O’Donovan wrote: “About picturing a ‘lobster’ [the usual practice in art history today is increasingly to call it a crayfish]…”

I deliberately call it a crayfish based on my observations of where this symbol was substituted for a crab and not because of anything anyone else has written. I noticed that the coastal zodiacs had a higher proportion of crabs to represent Cancer (almost all English zodiacs use a crab rather than a crayfish). This is not surprising, as crabs and lobsters live in salt water and crayfish live in fresh water.

Many people in inland areas had never seen a crab or lobster, so it is not surprising that many of the crayfish zodiacs are from inland areas where crabs (and lobsters) don’t exist. It is particularly interesting that the Rivipulli zodiac, one of the first that has a crayfish rather than a crab, originates in the mountains at the confluence of a large river system where crayfish were traditionally eaten in great numbers and where restaurants still feature crayfish on their menus. It is because of this that I chose to use the word “crayfish” rather than “lobster” when referring to the Rivipulli symbol.

As for earlier work about the zodiac symbols, I have been blogging about the VMS figures since July 2013. I did research on astrology years before I knew about the Voynich manuscript, so it was natural that I would be drawn to this section.

.

D. O’Donovan wrote: “But that is ongoing research, and not my research, so I’ll stop – but first I’d like to ask for details of those scholars whose opinions you mention in your post.”

My opinions are based on collecting, keying, and analyzing 540+ zodiac cycles (520 of which are complete cycles). I’m not aware of anyone else who has done this. No one has mapped datapoints for a series of specific combination searches either (I’m sure you know this), so obviously the data-map series is original research, as well.

D. O’Donovan wrote: “Since interpretation of the central emblems as a zodiac is more justified by longstanding habit than by what is actually in the manuscript, I feel that any final provenance must explain the ways in which the series differs – as it plainly does – from any known zodiac in the Latin manuscript tradition.”

It is important to distinguish between different research questions…

The ways in which the series differs might tell us something about the illustrator’s cultural background, but that is buy Lyrica mexico not the same question as where the inspiration for the figures originated.

It is very clear from the above examples that the VMS is thematically consistent with northeast France/Flanders and central-European zodiacs, even if the drawing style is different. As mentioned in the blog, these zodiac themes, when taken together as a group, are not characteristic of Scandinavia, England, Italy, Spain, eastern Europe or the Middle East.

Sorry JKP I’ve not been back to see your reply until now.

I think that you have correctly bracketed the period we should be looking at, but I must say that I reached rather different conclusions about the region indicated, and I also feel it necessary that we should account for substantial stylistic differences: for example, the star-topped wand given the figure generally identified with Virgo – or, again, the design for the balance, which is quite unlike any I’ve seen in any Latin European work – although it’s nice to see that you, too, have included both the beginning (the region around Lake Tiberius) and the end (Amiens region) of the transmission-line for the standing human archer for Sagittarius, and have moved beyond the usual limits of citing only manuscript art.

As for the lion with the tree in the background and the looped tail. That is actually an ancient design, but reappears in the Christian art of the Mediterranean first in Spain and southern Italy (specifically in Sicily), and remains a regular form in Jewish manuscript art. What is yet to be explored in detail (I don’t mean in the context of Voynich studies, necessarily) is the movement of these designs in parallel with the movements caused by expulsions, plague and so on. Not many people would think (for example) that the red glass introduced for works of Opus Francigenum (like the archer window at Amiens) itself came from the region of Lake Tiberius (near beit Alpha) in the form of tesserae, some of it as old as the Roman period there. It was brought.. and perhaps the local artisans too.. It would explain the sudden non-classical type’s appearance in Amiens at that time.

So, while I daresay it’s annoying that I cannot agree with your assertion that the centres of the Voynich calendar ‘fit comfortably in central Europe’, it’s not a disagreement for the sake of it, but the conclusions of evidence and research. Perhaps if you find an example of the ‘fairy and wand’ or the anomalous design for the scales (they are a type which is attested, but not in Europe), then we may be closer to an accurate idea of where the drawings originated. As I said in treating these, I think they had reached northern France by as early as the tenth century, but perhaps you are closer to the mark with the 12th.

Diane, I think you might be confusing two different issues: 1) the origin of the illustrative themes, and 2) the origin of the person who drew them. As I said in the post above, these are different research questions.

1) The origin of the themes (which is the topic of this blog) points to the Holy Roman Empire (essentially central Europe) and northeastern France/Flanders, as is clearly shown by the points on the map. There isn’t any evidence to indicate otherwise. Whoever drew them was exposed to zodiac illustrative combinations such as the archer with legs/crayfish-Cancer/”affectionate” Gemini/etc.—combinations that simply did not occur in other regions in the more than 500 zodiac-series studied.

2) Whether the person who drew them was from central Europe is a completely different question and I do not address it in this post because it is more difficult question to answer. The person who drew them might be from Sweden or Greece, Egypt, the Levant, Morocco, Dalmatia, Czech, Iberia, Bulgaria, Turkey, Tunisia, Sardinia, Malta, Portugal, Aragon, Provençe, Naples, or any number of places. We all bring our cultural filters with us. The problem is that it’s difficult to know which details were borrowed or copied from existing sources and which ones were inserted by the illustrator’s personal experience and cultural heritage.

.

To say that we disagree is to assume we are trying to answer the same question and I don’t think we are.

I wanted to determine where the themes originated. The findings are clearly illustrated on the map. The person who drew them might be from somewhere other than central Europe. In fact, my feeling from the time I first encountered the VMS is that the drawings might be by someone who was born in or spent time in the Mediterranean region (which includes many different nations and cultures), but this is harder to study or substantiate.

People in the Middle Ages moved around, a lot, often traveling thousands of miles to study at different universities or to seek patronage from different kings or emperors. There’s no reason why the VMS illustrator had to be from central Europe, but the exemplars for the VMS zodiac themes are most certainly from the Holy Roman Empire and the fringes near the Empire in the region of Flanders/NE France, as the evidence so far indicates.

JKP – when saying ‘how it differs’ I’m not speaking about differences in style so much as in content. That is, a zodiac is formed as a 12 fold sequence. What we have is not that sequence. I accept it was meant for a calendar – at least from the time the month-names were added, but there again some explanation must be given for there being two ‘Aprils’ and so on. The habit has been to just call it a ‘zodiac’, and accept the doublings and absences without attempting to explain what purpose these differences present.

If a square consists of four sides but what one has is a figure of seven sides, it won’t do to ignore the three and call it a ‘square’ – even if the figure has been formed by a square interlocked with a triangle. Yet in speaking of the series of calendar centres, the thing is deemed a ‘zodiac’ even though what we have doesn’t meet the term’s definition. What I’m saying is that the differences can’t be presumed an error, so that we only explain what we imagine it *ought* to be. One has to explain what is actually there, in the manuscript.

I think Koen’s recent work on the ‘crayfish’ lobster is probably the best lead we’ve had so far.

Thank you for publishing my comment, and for replying to it, even so indirectly.

Diane, when I refer to zodiac figures, I’m not talking about the folio, I’m talking about the figure in the middle. I don’t know what the nymph drawings surrounding the figures represent. They look to me like cycles of life (I’ve blogged about this), but whether they relate to the zodiac figures or not, I don’t know. Maybe they are a lunar calendar. Maybe they are good and bad days for bloodletting. I haven’t studied them in depth. I’ve been much too busy researching zodiac figures, plants, and the VMS text.

The month names that have been added in a later hand have always looked to me like an attempt to decipher the manuscript. Zodiac figures have long been associated with months, just as the 12 labors have long been associated with months, so it would not be unusual for someone to add month names to zodiac figures if they thought some of the VMS text might include month names and they were trying to match them up.

Great collection of images, i had not seen many of these, and the mapping is very interesting.