24 March 2020

I’ve mentioned a few times that maybe the Voynich Manuscript was a family project. This seems possible because medieval fathers sometimes created books of wisdom to hand down to their sons. One medieval family codex might be of particular interest to Voynich researchers because of visual similarities to the rosettes folio.

A Book Disembodied

The Cocharelli family previously of Provençe and Acre settled in Genoa and created a beautiful 14th-century codex for their children. Parts of it are based on stories told by the compiler’s grandfather. It was produced around the 1320s or 1330s, but has a murky history. At some point it was cut into pieces.

S. Nicolini (University of Bologna) reports that the cuttings appeared inside a 15th-century missal in the 19th century and were sold as part of an anonymous book collection.

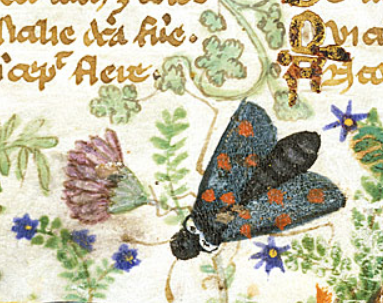

Clippings have turned up in several different countries: England, Germany, Italy, and the United States. Some of the content is allegorical, being a treatise on the vices, but there are also historical events, and the folios are enlivened by naturalistic images of flora and fauna that would appeal to any age group. The drawings are surprisingly detailed considering the small size of the codex (approx. 160 x 99mm):

I have collected links to the fragments so they can be accessed from one place:

- BL Additional 27695 – 15 fragments, including prologue, heaven and hell, vices of Envy, Avarice, and Gluttony, Adam and Eve, and notably the sack of Tripoli and death of Philip IV of France

- BL Additional 28841 – exotic animals, marine life, insects, rodents, along with verse about the history of Sicily

- BL Egerton 3127 – 4 fragments (2 leaves) of history and natural history

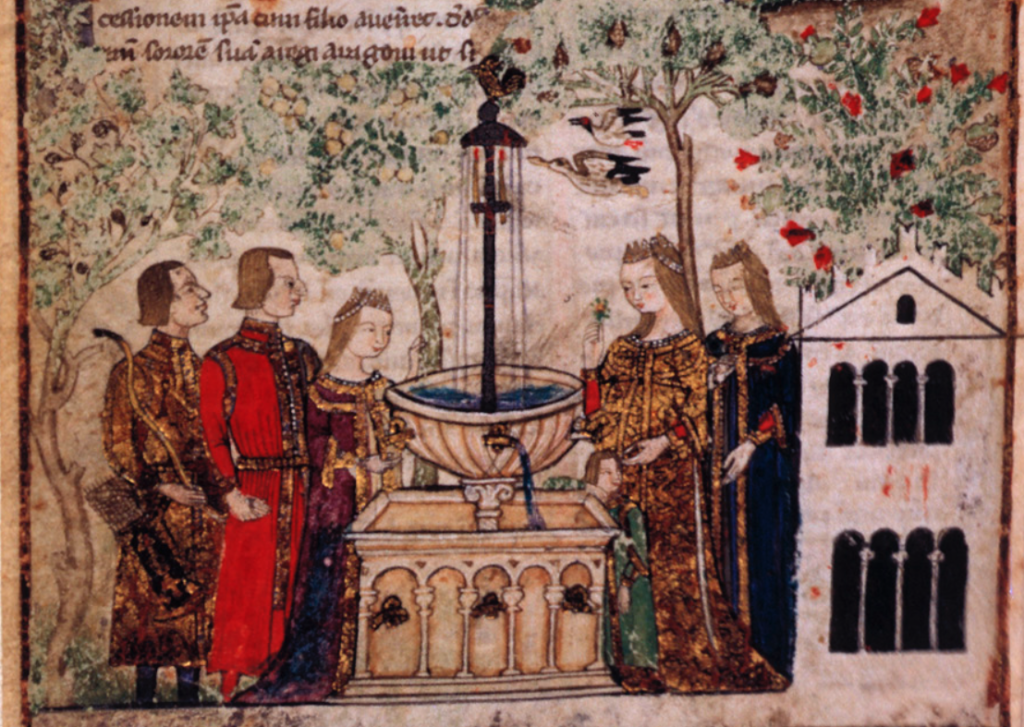

- BL Egerton 3781 – 2 fragments of a courtly garden scene

- Museum of Art Cleveland, Ms. n. 1953.152 – leaf of Accidia and her court

- Museo del Bargello, Ms. inv. 2065 – Siege of Acre

- Fragment sold as part of Eine Wiener Sammlung, Berlin (12 May 1930)

The illuminators are currently identified as the Master of the Cocharelli Codex (active in Genoa, c. 1330) and the Monk of Hyères (disputed). The sequence of the illustrations is considered by researchers to be different from the original order.

Multicultural Influences

Parts of the manuscript are in a more eastern style and there are several black people in African dress in the main illustrations and in the borders, as well as a person in the center of a feast who looks Asian:

It makes you wonder if the grandfather who related these stories was a seafarer who traveled widely. There are documents that support the presence of Pellegrino Cocharelli at some of the locations mentioned in the codex (C. Concina, 2016).

One of the Egerton 3781 fragments includes this image of a garden fountain, and if you look closely, you will notice to the right, there is a building with arches and Ghibelline merlons. Genoa was well within the purview of the Holy Roman Empire in the early 14th century (the HRE included Rome and much of Burgundy/Provençe at the time):

In this illustration on the page with text about the vice of Luxuria (lust), we see a maiden feeding a bird next to an architectural birdhouse that has Ghibelline merlons between the three towers:

Ghibelline merlons were one way in which Italians, especially those in an east/west belt where Italy spread out into the wider geographical region of Lombardy and Bohemia, signaled their allegiance to the HRE (in opposition to the pope). This political implication continued until about the mid-15th century after which the merlons gradually became more decorative than political (and thereafter spread to other areas).

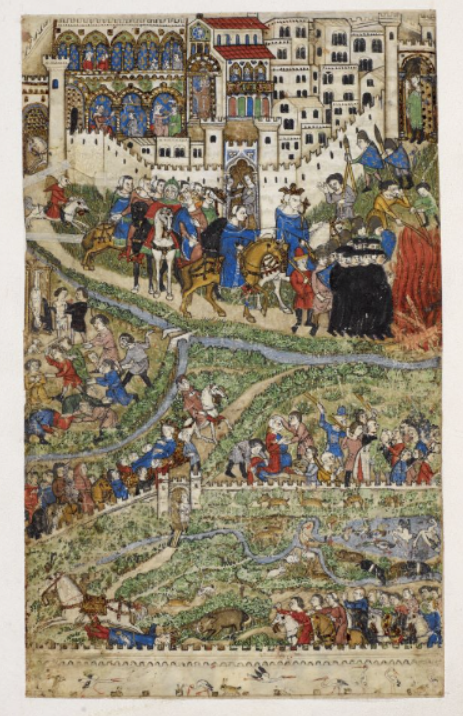

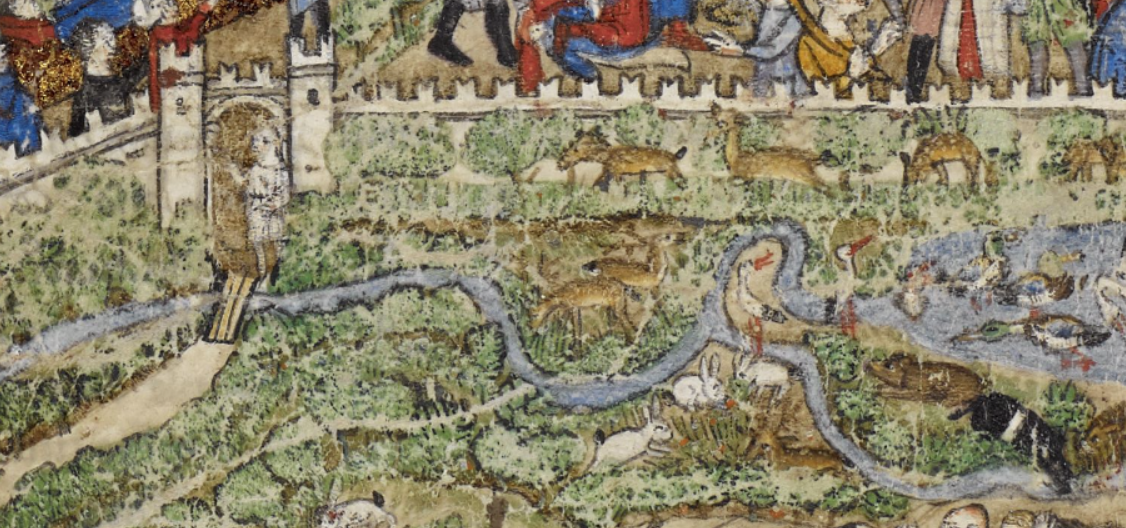

In the following battle scene from BL Additional 27695, there are square battlements on all the walls and towers except for the central tower, which has swallowtail Ghibelline merlons at the top. Since this represents the sack of Tripoli (Lebanon), it seems probable that the Ghibelline merlons are symbolic rather than literal, but installations of the Knights Templar sometimes had Ghibelline merlons, so perhaps they existed to a limited extent outside of northern Italy before the late 15th century.

In the waters of this elaborate illumination, there are four galleys from Genoa, in addition to others from Pisa and the Veneto:

In the 13th and 14th centuries, there were considerable tensions between the papacy and various kings and emperors in the late Middle Ages. Philip IV of France (1268–1314) aggressively challenged the power of the pope and the increasingly powerful Knights Templar. He gave important positions to his family members and even attempted to install a relative as Holy Roman Emperor to enlarge the kingdom of France.

The Cocharelli family recorded the arrest and torture of the Templars by Philip IV for a variety of charges, such as heresy, black magic, and financial corruption. In 1310 and 1314, King Philip had many of them burned at the stake. But his dreams of a large consolidated empire withered a few months later when he suffered a stroke while hunting in northern France. He died soon after.

Swallowtail Merlons in the Voynich Manuscript

In the Cocharelli illustration below, the roundup of the Templars is shown in the top half of the folio. The walled city has Ghibelline merlons on the front of the complex, but not the back. This is similar to the small drawing of a walled city or castle in the upper right section of the VMS rosettes folio.

The walled garden at the bottom of the Cocharelli folio, depicting game animals and the death of Philip IV, is completely surrounded by a long wall with Ghibelline merlons. In the VMS, there is also a long wall on one of the sections connecting two rosettes, but I wouldn’t describe this as a garden wall, it looks more like a long city or castle wall:

Since the events surrounding King Pillip in the Cocharelli codex took place in France, it is not likely that the merlons in these illustrations are literal, but since Philip IV was ardently against the power of the papacy and open to allegiances with the HRE, and the illustrators were Italian, it may have been their way of diagraming his political leanings:

The VMS is also known for its elaborate containers in the small-plants section and the container-like “towers” on the rosettes folio. There are also some interesting containers on Cocharelli folio f7v in a fragment that has been completely cut away from the text:

In contrast, the illustration of the Siege of Acre (Museo del Bargello), in which the Crusaders lost Acre, a city on the Levantine coast, Ghibelline merlons are not included except on a single portal in the lower center part of the city:

(Note, there is some dispute about this being Acre. Some scholars say Genoa, but the textual evidence seems to lean toward Acre.)

In a discussion of the possible ordering of the original Cocharelli codex folios, Concina mentions some of the political turmoil associated with the Guelfs and the Ghibellines:

In the summer of 1308 Opizzino Spinola of Lucoli proclaimed himself the only captain of Genoa by deposing and imprisoning Bernabò Doria, who was his co-ruler in the traditional diarchy established for the government of the city. Following this coup d’état, many leaders of the Ghibelline families of the Doria (including Corrado and his son Pietro) and Spinola of San Luca, as well as of the Guelf families of the Grimaldi and Fieschi, were forced to flee the city. In June 1309 those families exiled set aside their old differences and joined forces to defeat Opizzino and his army at Sestri Ponente, forcing him to take shelter in the castle of Gavi. On the same day, the Guelf and Ghibelline exiles entered Genoa, apparently without great losses….

In addition, if we consider historical references, we can glimpse a family [the Cocharellis] gravitating towards the Ghibelline party, the Doria and the Aragoneses.

—Chiara Concina (University of Verona)

Summary

As mentioned previously, the Ghibelline merlons in these drawings may be symbolic rather than literal. It’s hard to find evidence of this style of merlon outside of northern Italy/Lombardy/Bohemia before the latter 15th century and the Cocharelli drawings are from the 14th century when their geographical distribution was quite limited. But, considering that Philip IV of France was one of the more ardent opponents of the pope and friendlier than some French monarchs to the Holy Roman Empire (he was hoping to expand into that region as well, via family alliances), the Ghibelline merlon reflects his political leanings via a symbol that was familiar to Italian artists.

Here is a drawing of Padua, with a long wall and numerous towers topped by Ghibelline merlons, by Felice Celeste Zanchi c. 1300:

But are they real or symbolic? A 15th century drawing of Padua shows square merlons, so perhaps Zanchi added some from his imagination.

At times there is only a glimpse of the merlons, as in this illustration in BNF Latin 9333 (c. 1410s):

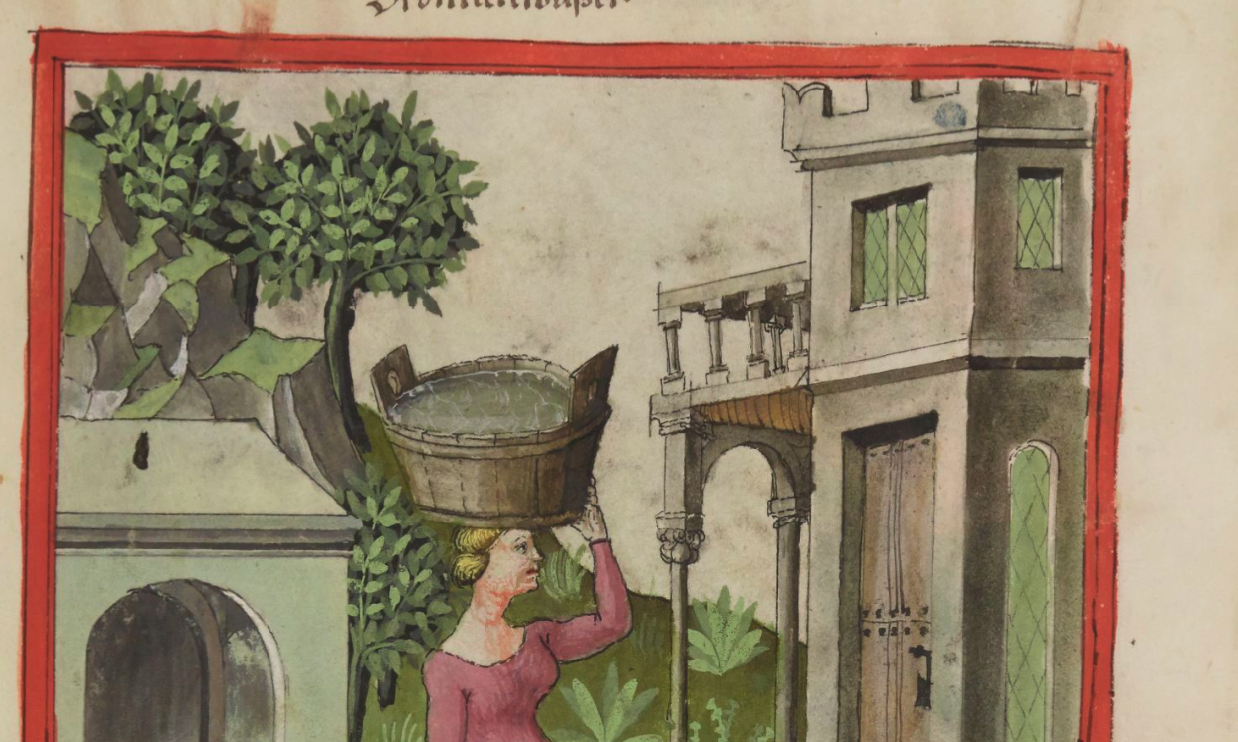

Sometimes the merlons are more clearly indicated, as in this earlier example of Tacuinum Sanitatis (Casanatense, 14th century):

So what about the merlons in the VMS rosettes folio. Are they literal or symbolic?

It is interesting that the walled city or castle at the top of the VMS folio was drawn with more Ghibelline merlons on the front than there on the back (similar to the Cocharelli depiction).

Is this how compounds were usually built? Or do the drawings in the two different codices have a common inspiration? Is the VMS merlon sending a political message? Is it a reference to a specific event? Or is it an actual place, a landmark to help a traveler find his way?

J.K. Petersen

© Copyright March 2020 J.K. Petersen, All Rights Reserved