VMS Marginalia—Who Wrote it and Where?

The last page of the VMS has always struck me as similar to a pidgin pigeon language. As I’ve noted in previous blogs, it’s mostly but not quite readable in German and I often wondered, in the early days of studying the manuscript, whether it might be medieval Yiddish. Even though there are many dialects of Yiddish, as are described in some detail by Alexander Beider, I didn’t want to commit too strongly to this idea because many medieval scholars studied at universities in several countries and picked up bits and pieces of local languages along the way—there could be several explanations for the mostly-but-not-entirely-German nature of the script.

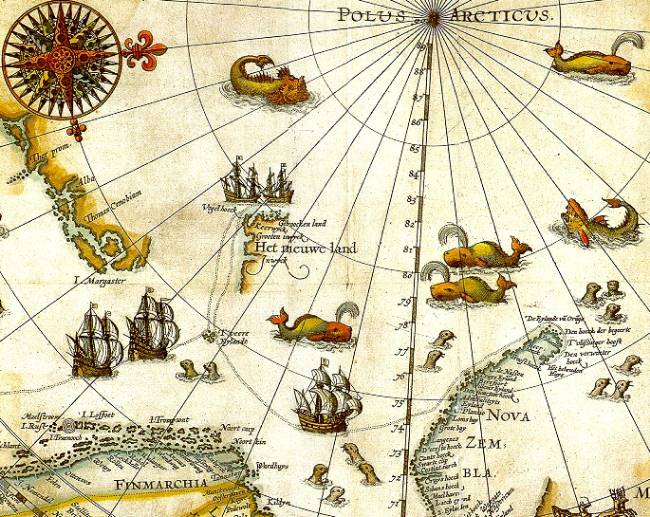

When I was looking into medieval languages that might have some relevance to the VMS, one of the blended languages I found particularly interesting was the pigeon-Icelandic spoken by the Basques. Icelandic is not an easy language to learn and Basque doesn’t resemble it in any way, and a visit to the little island requires a treacherous sea ride over particularly rough waters, so I wondered why the Basques would be motivated to learn a distant and seemingly impractical language like Icelandic, but it turns out that Basque whalers hunted the north Atlantic with some frequency and may have stopped on Iceland for rest, repairs, and supplies, eventually learning bits and pieces of a language very different from Basque (which is itself very different from most European languages).

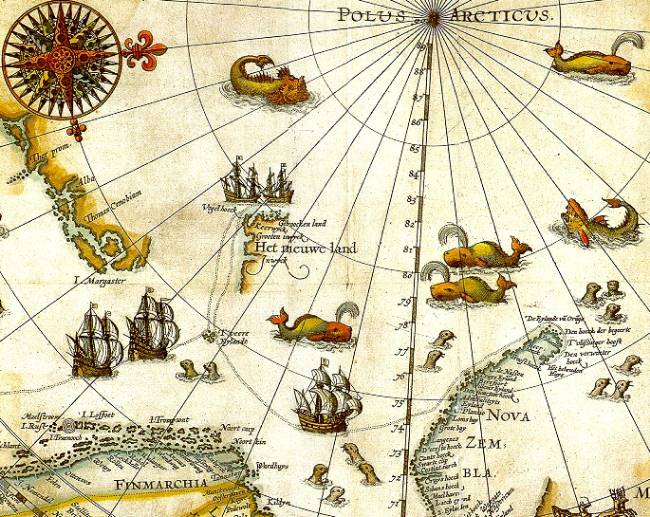

The whaling trade was one of the reasons sailors ventured into the perilous arctic, where they stopped in Iceland and, later, the remote town of Spitzbergen on an island far north of Norway. This is believed to be the first map of Spitzbergen, in the Arctic hinterland, published in 1599, and whales are prominently featured in its waters. [Image courtesy of Wikipedia.]

Basque oral history claims that the Basques discovered the New World before Columbus, something I think is entirely plausible—if you can make it from the Iberian Peninsula to Iceland, you can surely reach Greenland, and from Greenland to North America is a short hop compared to the original trip to Iceland.

A Basque cemetery dating to about the mid-1500s was unearthed in Labrador, Canada, and Basque shipwrecks have been found off the coast of Red Bay.

It’s possible some of the whale hunters reached the New World before 1492 following the same routes as the Vikings, and it occurred to me that they might have brought back plants that otherwise were not known in the Old World, but it doesn’t seem likely that whalers would be concerned about physically documenting plants. Whaling is a practical trade, not an exploratory venture (unless you’re exploring for new places to fish), and botanists weren’t usually passengers on whaling ships headed for the New World until after Columbus’s voyage. So I put the Basque-Icelandic-New World plants idea to the side for the time being and looked for other interesting language combinations that might shed light on the VMS.

Linguistic Alphabet Soup

Inspired by the Basques’ willingness to learn Icelandic, I sought out other blended languages and found so many of them, it will take years to sort it all out. As examples, the language of the Veneto includes many Spanish words and some Latin/French constructions, as well as influences from Dalmatian, Greek, and Albanian. The area north of the Veneto has a great diversity of languages, and the region of Provençe and northern Spain is rich in blended dialects. Lombardic in its original form was southern Scandinavian and other germanic dialects mixed with northern Italian.

Any region that was a crossroads for trade, or a hotly contested area in which the borders were constantly shifting, was usually rich in variations that might seem like polyglot to the modern reader.

How does this relate to the Voynich manuscript? Perhaps the marginalia seems strange because it is from a linguistic melting pot, but there are so many I can’t fit all of them into one blog, so I’ll start with Silesian, as it would follow naturally from my previous blog about VMS Sagittarius, and includes German dialects that might result in text that looks mostly like German but is confusing to read.

Silesian History

Silesia is on the shifting border between Poland/Prussia and Czech/Bohemia. Breslau/Wroclaw was at its center in the 14th and 15th centuries, when Wroclaw was part of Bohemia.

This area is mentioned in previous blogs as the origin of the oldest-known example of crossbow-Sagittarius. It is also the birthplace of a German-Silesian dialect that was almost eradicated after World War II, when the language was banned by the Communists. Both during and after the war, millions of Jewish and German inhabitants from this area were murdered and expelled by Nazis and Communists, forever wiping out a huge percentage of Silesian language, culture, and history.

The Silesian Language

Even though the Polish border is farther south now than it was in the Middle Ages, Silesian is still a dominant language in the section of Poland between north Poland and eastern Czech, so this region still retains a certain amount of linguistic and cultural autonomy. To the north and east are greater and lesser Polish and to the west, along the Baltic, are a number of mixed dialects. South of Silesia are a variety of Slavic languages and to the southwest, the primary language is Czech [map detail courtesy of Wikipedia]. Before WWII and especially during the Holy Roman Empire, there was a strong German presence. Before the Holocaust, this area also had a significant Jewish population.

Silesian-German

Silesian-German, a dialect of Silesian, has Franconian, Thuringian, and Saxon roots and today, due to the purges, only a small region west of the Oder-Neisse still retains the language, which is undoubtedly different from what it was in the middle ages due to the modernizing influence of German radio and television. Historically, though, many Slavs spoke German and the Germans, with their blended Silesian-German, understood Slavic-Silesian.

The Lach Dialect

In the same area, one finds the Lach dialect, a west-Slavic blend of Czech and Polish that was spoken from Silesia to Moravia. In the middle ages, some forms of Czech and Polish were mutually intelligible and today Lach is considered by some to be a dialect of Czech, and the forerunner (or at least a strong influencer) of modern Polish.

Lach may soon die out, just as Lombardian is dying out. The Lach youth are learning Czech and the Lombardic youth are switching to Italian—both languages may be gone in two or three generations but these and many others were alive and closer to their original forms when the Voynich manuscript was created.

We can only guess at how Lach and Silesian-German sounded in the 15th century, when Polish and Czech cultures intermingled with Saxon German (which itself included Nordic influences), but we do have some idea of how they were written from a number of manuscripts that have survived.

So Silesia is a region where many dialects existed in a small geographical area and where language shifted and blended, due to frequent changes in political rulership and immigration.

Pinning Down the Dialect

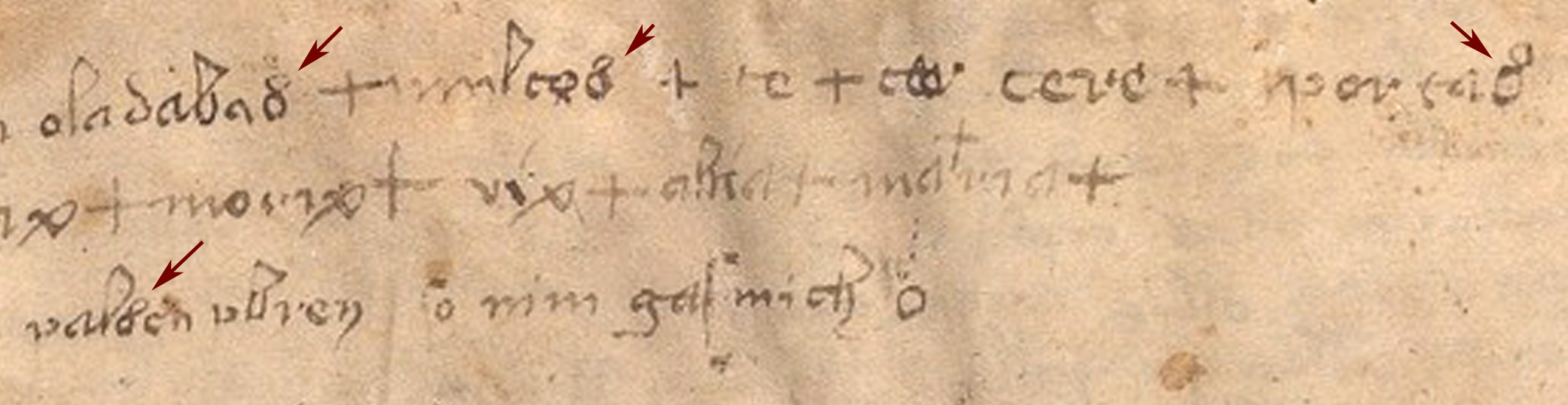

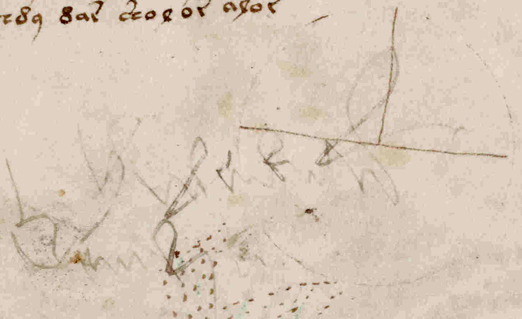

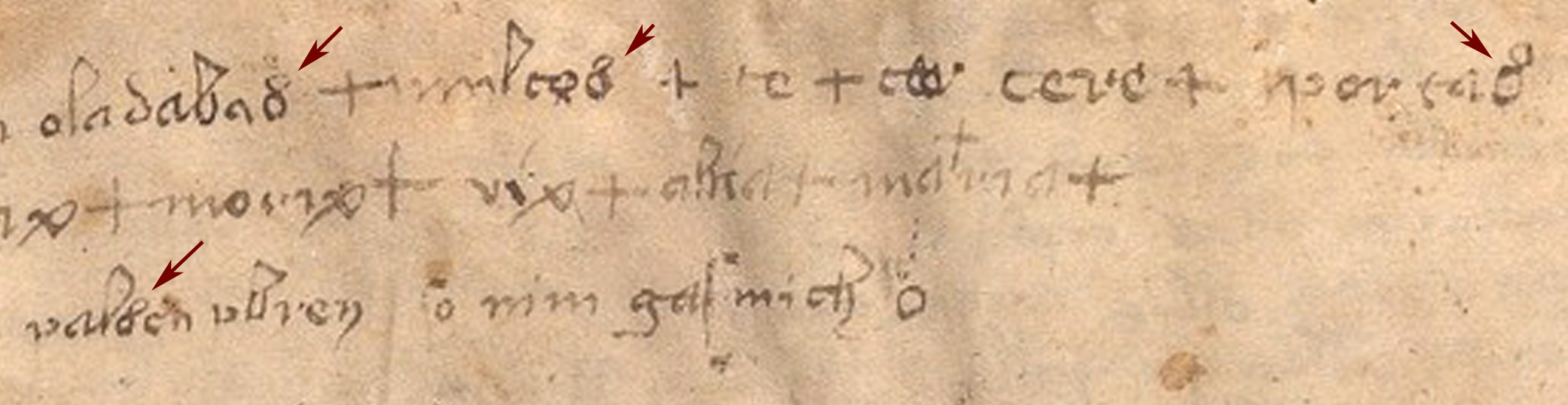

Might Lach or Silesian-German explain some of the peculiarities in the somewhat germanic text on 116v?

It depends how one interprets the words. If “pox” is meant to be “boch” (billy goat) then we already have some clues. The substitution of p for b was quite common in areas like southern Germany/Lombardy, Augsberg (which was written “Augsperg”), Dinkelsbühl, and certain towns along the Swiss-German border.

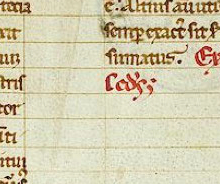

Substituting “x” for “ch” was less common than substituting “p” for “b” but it did happen in some areas, especially those in which Greek was taught along with Latin. The familiar abbreviation xpo/xps/xpi/xpt for Christ (see right) is derived from Greek, with the x and p at the beginning descended from “chi” and “rho”. Thus, one occasionally sees chi (x) used for “ch” in Latin or other texts. Putting those pieces together “pox” becomes “boch” (goat) as suggested by Johannes Albes (and perhaps others).

Substituting “x” for “ch” was less common than substituting “p” for “b” but it did happen in some areas, especially those in which Greek was taught along with Latin. The familiar abbreviation xpo/xps/xpi/xpt for Christ (see right) is derived from Greek, with the x and p at the beginning descended from “chi” and “rho”. Thus, one occasionally sees chi (x) used for “ch” in Latin or other texts. Putting those pieces together “pox” becomes “boch” (goat) as suggested by Johannes Albes (and perhaps others).

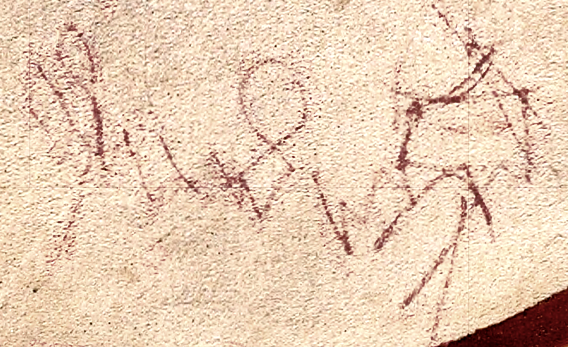

It is not only the way the words are spelled, but also the way the letters are written that provide clues. The use of a figure-8 for D or S was not common uncommon (I’m leaning toward this being S since the previous D has an open loop and a word like “portas” is more likely than “portad”) but I sometimes wonder if it’s a ligature, or a symbol for another sound, such as ç or z as it is pronounced in Castilian Spanish.

Usually the figure-8 shape was written slightly asymmetrical to distinguish it from the number 8, but in a few areas (e.g., eastern France), the difference between “d” and “8” was less distinct and discerned by context. On folio 116v there aren’t enough instances of the figure-8 character to know for certain whether it’s D, S, or something else, but the fact that it exists in the marginalia (and possibly also in Voynichese) might be a regional indicator.

Geolocation

So, for quite a number of years, I have collected information on regional dialects, along with samples of text with scribal hands that resemble those of the main text and the last-page marginalia. When evaluated together, I was hoping they would help geolocate the VMS scribes.

This is a slow process and a certain amount of luck is involved. Many manuscripts have been lost in wars and fires and many sit unseen in private collections and libraries, so the odds of finding a match to the VMS handwriting is not very good. Nevertheless, I decided to try.

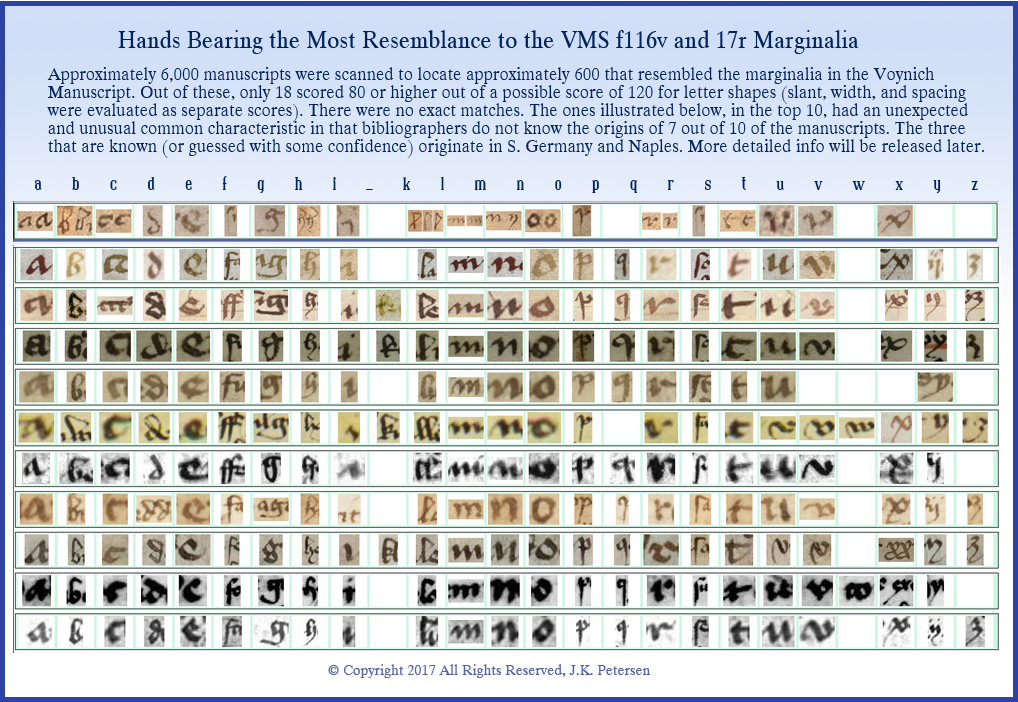

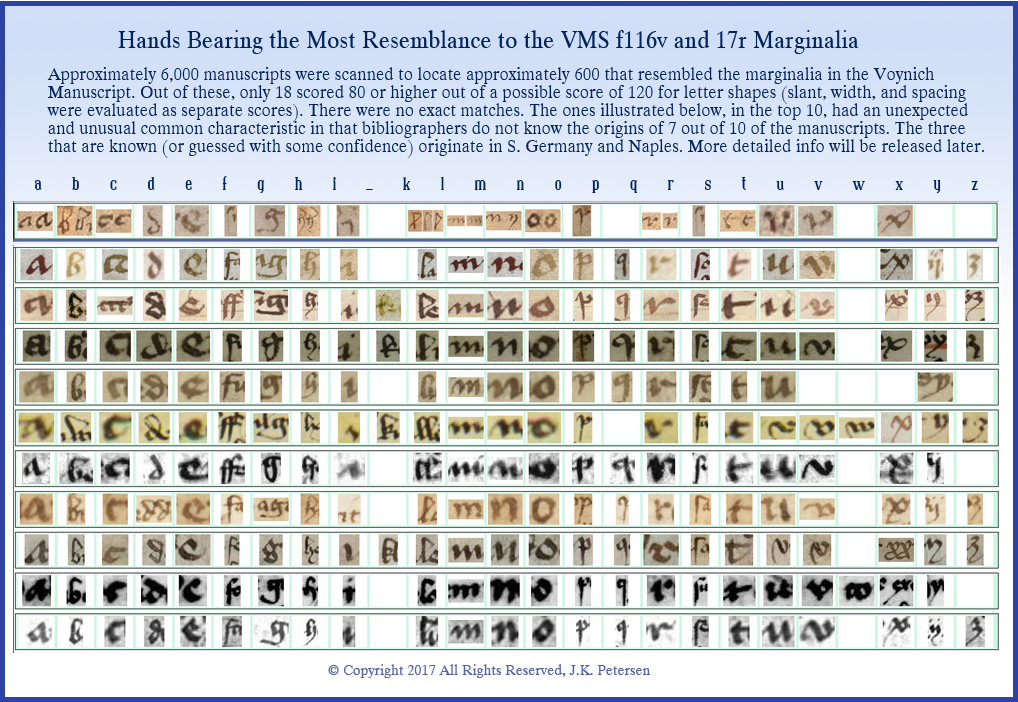

To date, I have about 600 hands that bear some resemblance to the handwriting of whoever penned all or most of the text on 116v. I had to study about 6,000 manuscripts to locate these samples, so only about 10% of the hands surveyed so far were similar enough to include in the sampling.

To evaluate the hands, I developed a mathematical system that describes each letter individually and the alphabet as a whole, and which also assigns scores for pen width, slant, letter spacing, and word spacing.

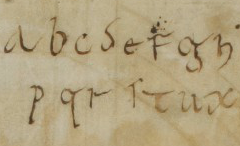

Unfortunately, neither the main text nor the marginalia provide a full alphabet but I am strongly convinced that the hand on f116v is the same as that on f17r, which helps fill out most of the alphabet for the marginalia, except for “k”, “q”, “y”, “z”, and “w” (“w” was not used in Latin but was in German). In Latin, there was usually no distinction between “u” and “v” but one was sometimes made in German, and the marginal writer does appear to write “u” and “v” differently, so I treated them as separate letters. The letter “j” was not typically used in the early 15th century. Normally the j sound was expressed with “iu” or “io” and sometimes written with an embellished “i” that resembles a modern “j”, but the “j” wasn’t usually treated as a separate letter when the VMS was created).

Thus, 20 letters are available for comparison (plus the figure-8 character, which might stand for terminal-S, D, or something else, and was not included due to its status being unknown).

When given numeric scores for similarity ranging from 1 to 6, with a perfect match for all the letters being 120 (not counting the spacing and slant variables), it becomes possible to search and sort the samples, and more objectively compare various hands to the VMS.

A Brief Overview of the Results So Far

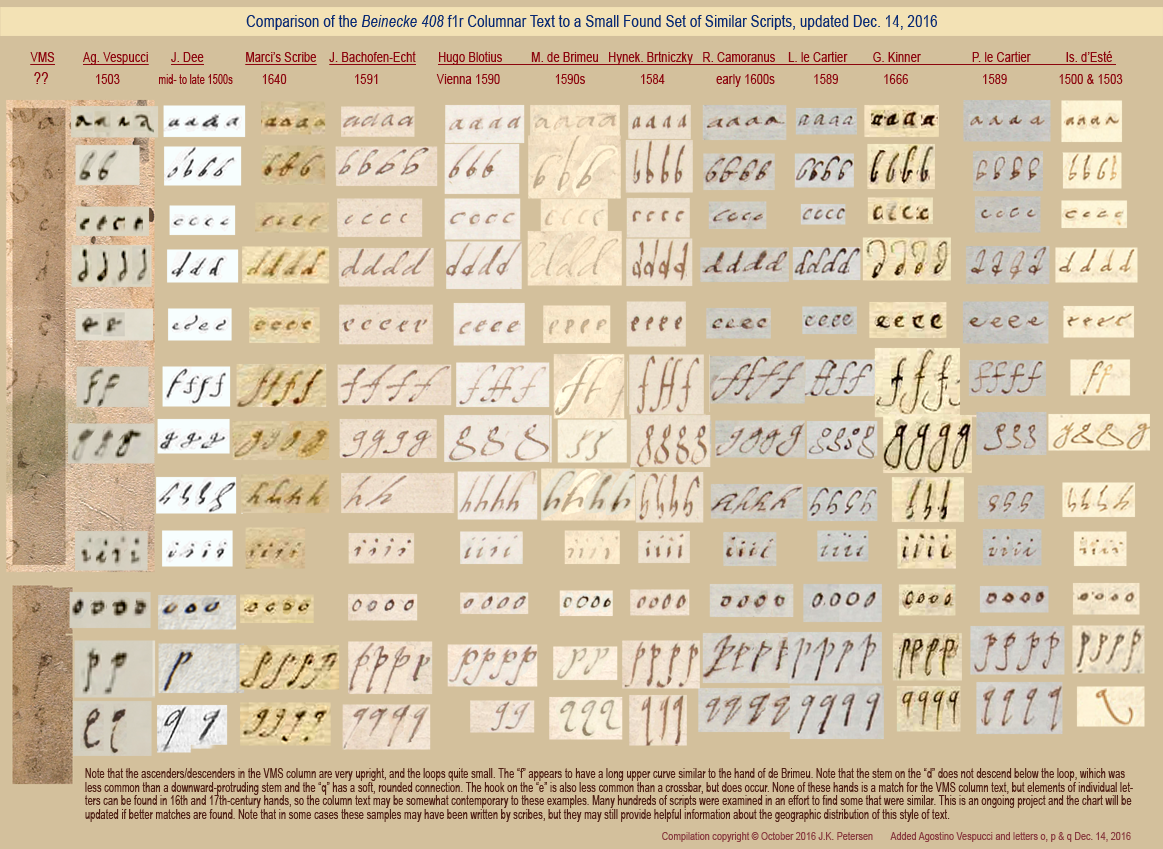

Out of approximately 600 reasonably similar hands, only 18 scored 80 or higher on a scale of 1 to 120. This form of writing is loosely called Gothic cursive, although there are some traces of book-hand mixed in and it is sometimes referred to as Gothic quasi-cursive.

These are the ones that are most similar:

[Postscript 9/7/17: I noticed a copy-paste error in Row 7 Column 1 (the letter A), so I have corrected it and re-uploaded the chart.]

As can be seen from the top ten examples, which scored from 81 to 87, the scribes who wrote in hands most similar to the VMS marginalia did not typically write an unlooped “d”, a flat-bottomed “b”, or a “u” with serifs—the VMS hand differs in these respects not only from the hands that most closely match, but also from hands that scored in the 70 to 79 range, so these characteristics can be used as markers to help recognize an individual person’s writing. Unlooped “d” is not uncommon, it is simply less common in hands that most closely match the overall alphabet for the marginalia.

What especially surprised me about these 10 samples, which I hoped would help geolocate the marginal writer, is that historians and bibliographers don’t know where they came from. Seven out of ten have undocumented origins. In contrast, the origins of those that score in the 77 to 80 range are mostly known.

Is there a bigger mystery surrounding manuscripts with hands similar to the marginalia writer’s? Could there be a group of manuscripts from a particular area that were obtained or transmitted in some unusual way? We know that the VMS is listed in the Vatican catalog, but never made it to the Vatican library because the Jesuits, under a promise of secrecy from Wilfrid Voynich, sold it to the book dealer from America rather than conveying it to the Vatican. Might there be other manuscripts with shadowy histories?

Patterns in Subject Matter

When looking for handwriting samples, I scoured every kind of document I could find, including incunabula, legal documents, and manuscripts. I didn’t want my assessment of the handwriting to be influenced by the subject matter or source of the documents. Once I had enough samples, I began to study their subject matter. The top samples (which include documents with both known and unknown origins) fall into the following categories:

- Alchemical (1 example, origin uncertain, possibly Austria, Bohemia, or Germany c. last half 15th century)

- Saintly Miracles (1 example from a manuscript written in several different hands, the sampled hand may have been added c. 1400?, possibly from Germany)

- Collections of sermons or theological treatises (3 examples, possibly from Germany, but this is not certain; 1 example of unknown origin; 1 example from Lund region; 1 late 15th-century example from the Alsatian region)

- Mortuary Roll (2 examples in a document that includes different hands from different regions, 1458 to 1459, possibly from Flanders/Normandy area)

- Armorial Roll (1 15th-century example in a Tirolian collection that includes different hands from different regions)

- Homer’s Epic (1 example from Naples region, possibly late 1300s)

- A handbook of fortune-telling, charms, medicine, virtues of plants (1 example from England, possibly mid-1400s)

- Selected stories of Petrarch (1 example from S. Germany, c. mid-1400s)

- Frontismatter in another hand on a c. 1380s Czech book of hymns and prayers (1)

- Endmatter on a back leaf in another hand on a manuscript from c. 1300 Bologna, but which is housed in Germany and may have been added to in Germany in the late 14th century

- Legal document: 1360 Charles IV grant (1 example from Nuremberg, Germany)

- Astrological text with zodiacs (1 example, possibly from the Alsatian region)

- Tristan and Isold themes (1 example, c. 1330, Veneto)

Clearly, those who used this style of writing come from several different areas and a number of different occupations and copied or wrote on different subjects. The examples range from the early 1300s to the late 1400s, a time period that is consistent with the use of Gothic cursive in general and which could indicate marginal writing that is either contemporaneous with the VMS, or later, or even earlier (although this seems less likely as there are two Voynichese tokens inline with the rest of the text on f116v).

The examples are both ecclesiastical and secular and only include a couple that delve into the occult. None of them are specific to herbs or bathing, although one does mention plants and includes charms (Trinity College MS O.1.57) and uses the Greek sigma symbol as a terminal-s. For the most part, however, they are practical collections of knowledge. None include cipher script. The only significant pattern that emerges is that the majority, where origin is known, are from germanic regions, which is perhaps not surprising, since the marginalia itself is somewhat germanic.

I have much more data and commentary than I’ve posted in this brief summary, and will report further on the marginalia (and on the main text) as I have time.

J.K. Petersen

© Copyright 2017 J.K. Petersen, All Rights Reserved