Folio 116v Revisited

In 2013, I posted a couple of times about Folio 116v, which is sometimes referred to as the last page of the Voynich Manuscript. I also suggested, as I worked through my journey of personal discovery, that it might be a healing charm. I knew nothing about healing charms before trying to puzzle out the VMS, but I was following a hunch that it might be associated with magic when I saw the strange word oladabas. I later discovered, in 2013 and again in 2015, that abracula was a charm word (a very old and and venerated one) used to cure fevers, and posted some examples of 15th century charms, which follow a format surprisingly similar to the VMS text.

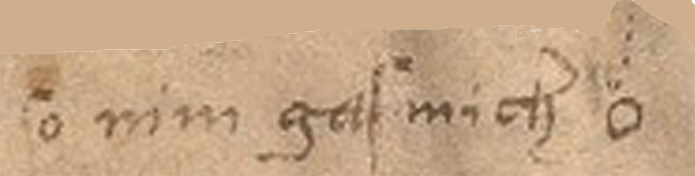

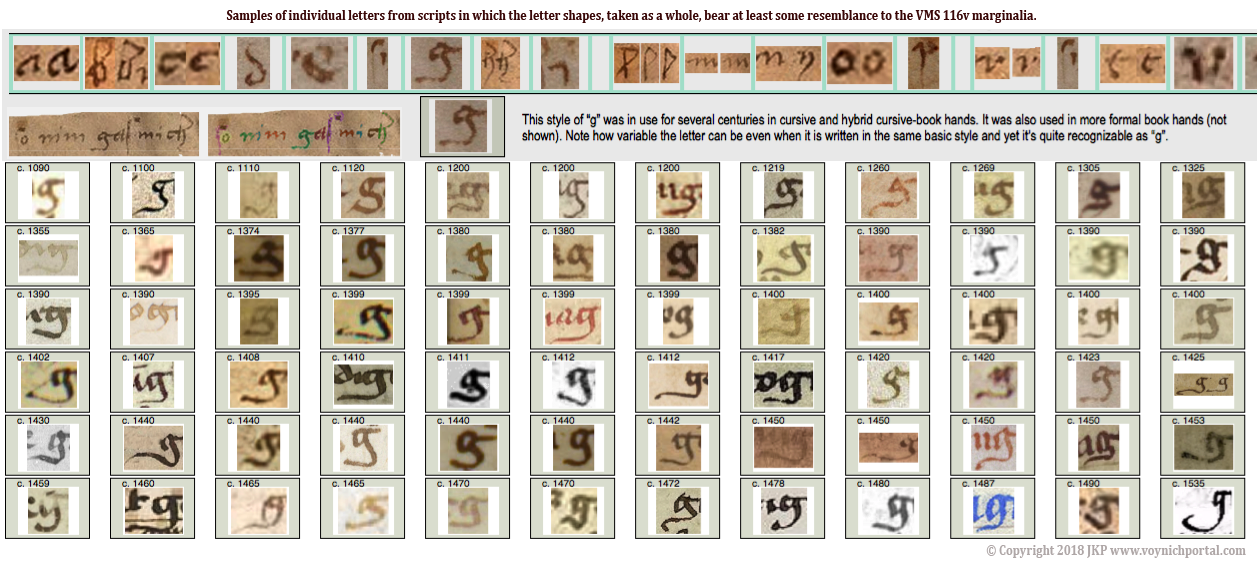

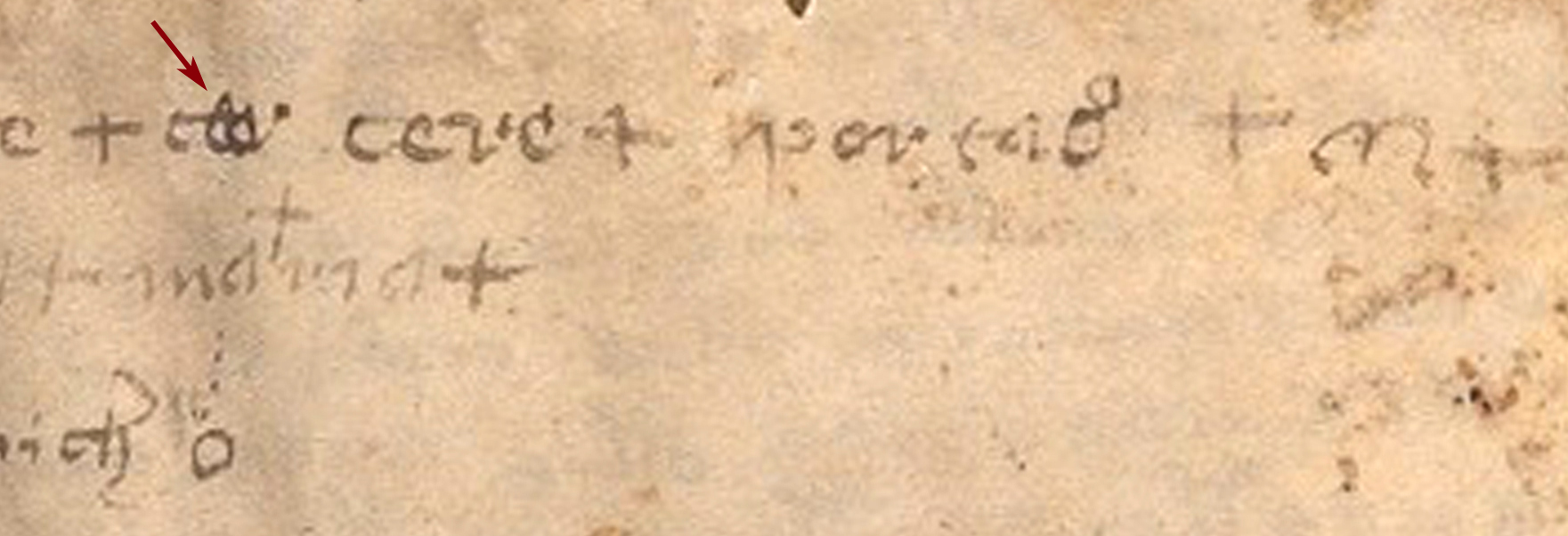

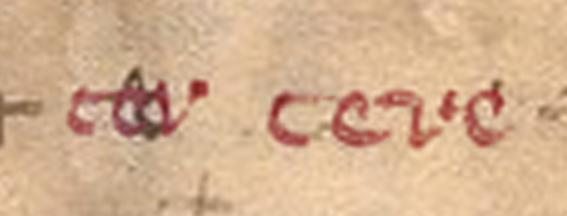

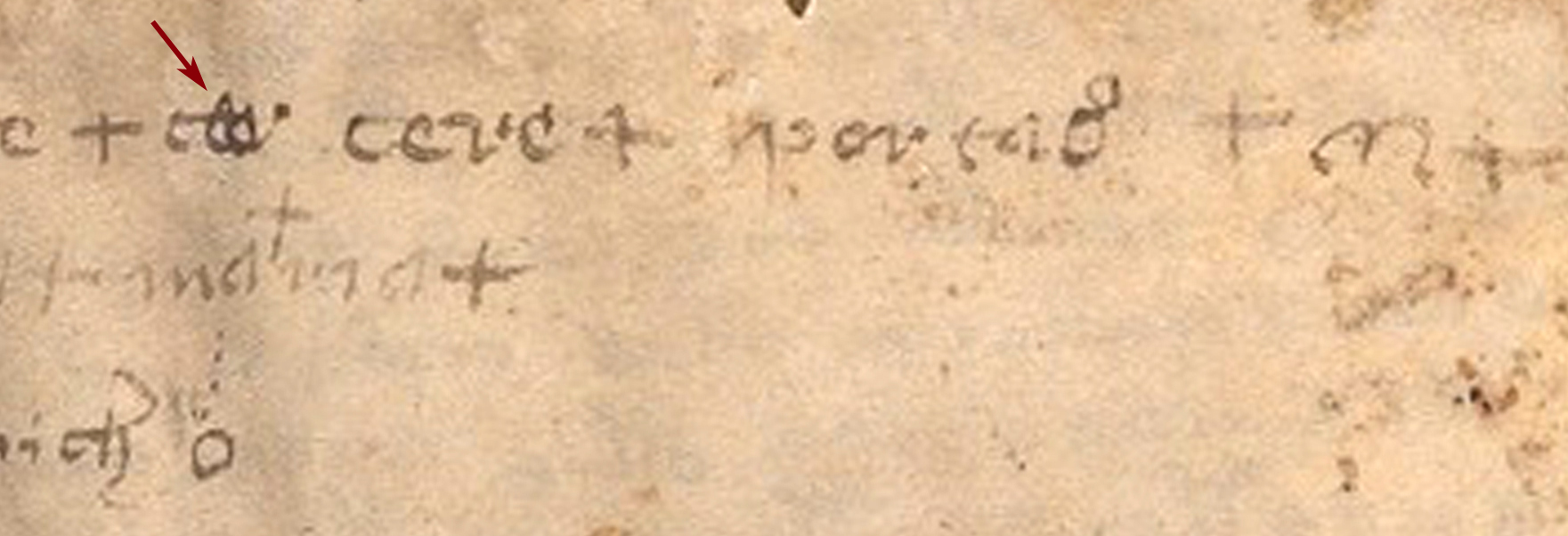

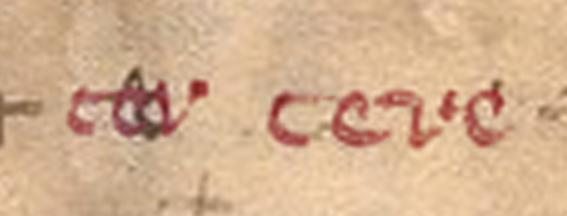

Considering how little is written (and drawn) on Folio 116v compared to most other pages, it’s surprising it has generated so many questions. One of the persistent challenges is the interpretation of the characters, some of which are faded and some of which are unconventional. I can read Gothic Cursive better now than I could in 2013, but that doesn’t help when a word is a blobby mess like the one in the middle of the first row of the main body of text (marked with an arrow):

Deconstructing the Blob

I didn’t pay any attention to what others proposed as the reading for this word because I was so focused on other aspects of the page that I never followed it up, but the subject was raised on the Voynich forum today and I thought it was time to post my impression of what the letters might represent.

In 2013, I thought the word-group in question might be a messy rendition of toe because “o” and “e” are sometimes combined in old manuscripts as œ. After looking at it for a while longer, I realized the explanation might be something completely different.

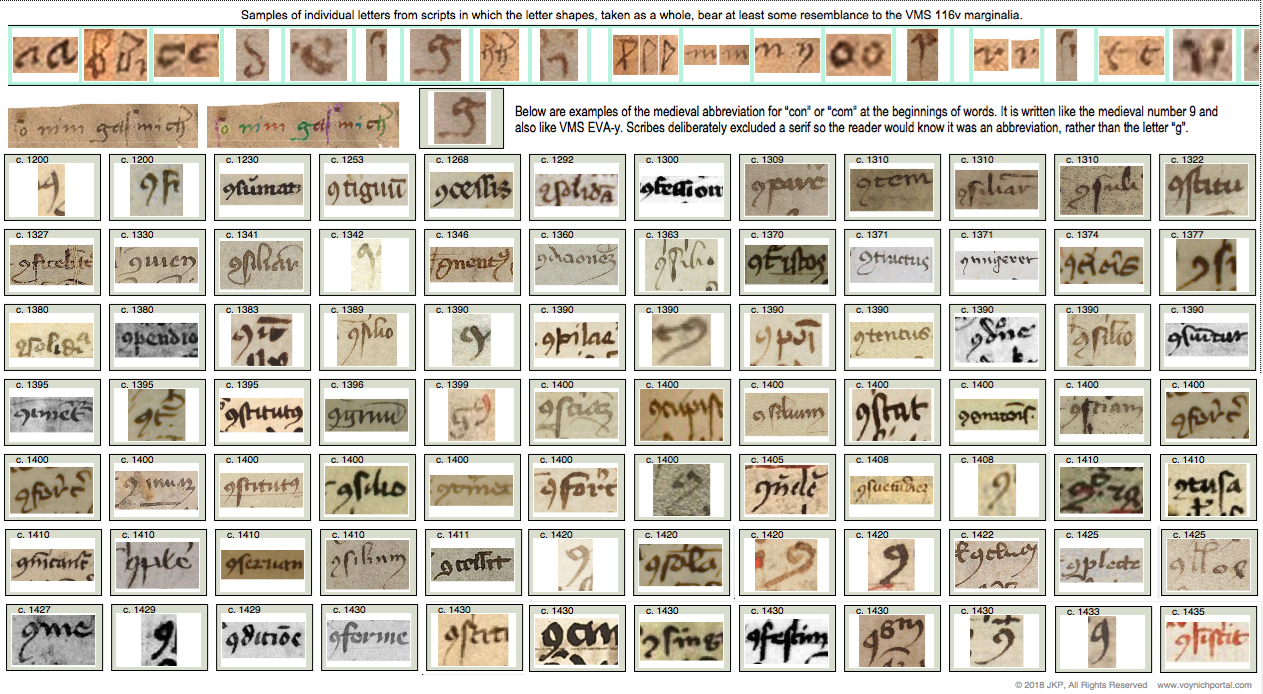

Let’s say, for example, that this was originally written as a bench character (EVA-ch). The bench char isn’t only a Voynichese char. As I’ve mentioned before, it’s also a common Latin ligature that can represent a wide variety of combinations of “t” “c” “e” and “r” characters, since they are similar to one another in Gothic cursive. In fact, in some manuscripts, it’s hard to distinguish “c” from “e” or “t” from “c” without context.

Let’s say, for example, that this was originally written as a bench character (EVA-ch). The bench char isn’t only a Voynichese char. As I’ve mentioned before, it’s also a common Latin ligature that can represent a wide variety of combinations of “t” “c” “e” and “r” characters, since they are similar to one another in Gothic cursive. In fact, in some manuscripts, it’s hard to distinguish “c” from “e” or “t” from “c” without context.

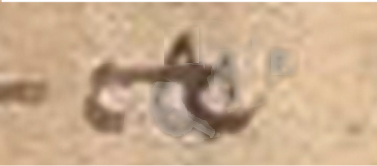

So, if it’s a bench character, maybe it’s a bench char with a cap or maybe the “cap” is part of the corrected shape or something not used anywhere else. I’m not sure. The cap is smaller and lower than usual, so it might be part of the corrected shape, but we don’t know if the script on the last page is written by the Voynich scribe or someone else who is somewhat able to mimic VMS text but doesn’t do it exactly the same. In the example above, I’ve lightened the shapes that appear to have been added after the initial shape was drawn. I left in the “cap” or “elbow”, but it’s probably best to picture it in your head both with and without the cap-shape since its connection with the other shapes is unclear.

All right. So let’s say for the moment that the scribe drew a bench character. What happened then? Why did he turn it into an unreadable mess? Perhaps the scribe was trying to correct an error. Maybe it’s Voynichese and he didn’t want to give things away. Maybe it’s a common Latin ligature and he decided it looked too much like Voynichese and could be misinterpreted later. Maybe it’s simply a mistake.

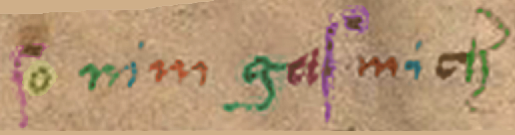

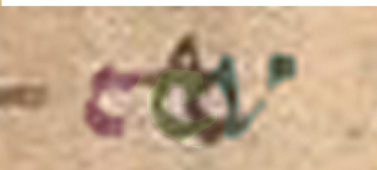

Here’s what I think the scribe may have tried to do to correct it… I’ve added colors to the letters so they’re easier to see because I think the answer may lie right in front of us.

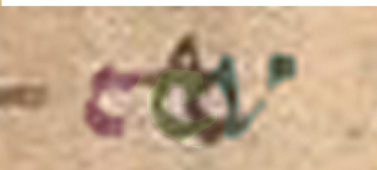

Here’s what I think the scribe may have tried to do to correct it… I’ve added colors to the letters so they’re easier to see because I think the answer may lie right in front of us.

In this illustration, the “c” or “t” is purple, the added “e” or “c” is green, and the added “v” or “r” is bluish. Note how the bench char is still in the background, making it hard to clearly see the letters in front even when they’re highlighted with color? So… if it’s a mistake, adding the letters didn’t fix the problem.

What was he trying to write? Was it tev/ter/tar or tcv or ccv or cev or cer—all of which might have been written with the first two letters as a ligature in Latin? I think maybe it’s “cer” or “cev” (ligature ce plus v) and he never finished correcting it because it wasn’t working, so instead of taking the time to scrape away a mistake—he wrote it again correctly as the next word, spaced out better and not blobby, to create “ceve” or “cere”.

Plausible?

I don’t know. It’s just an idea, I can think of other interpretations, as well, but I think it’s worth mentioning in case it sparks some fresh thoughts about how to read it.

J.K. Petersen

© Copyright 2016 J.K. Petersen, All Rights Reserved