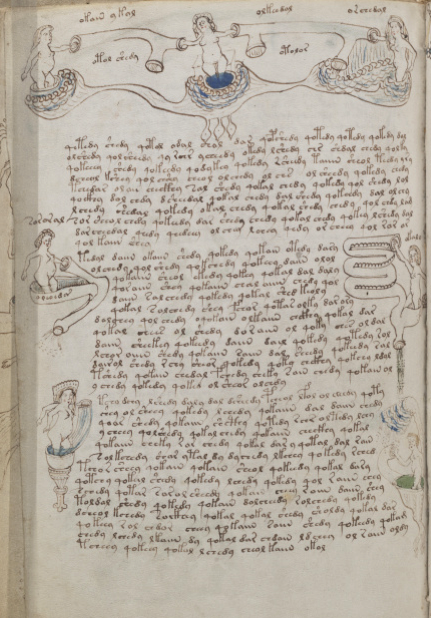

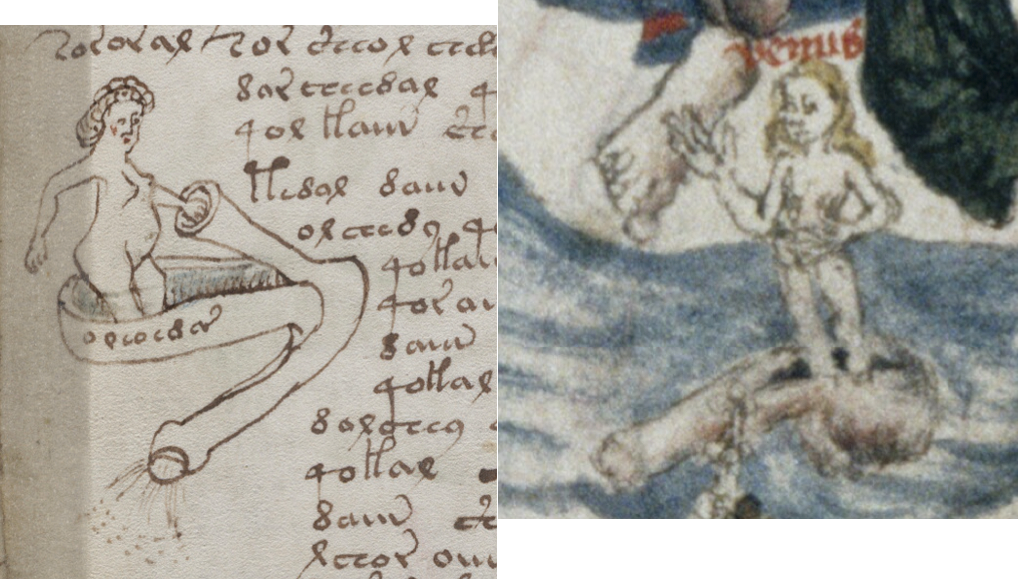

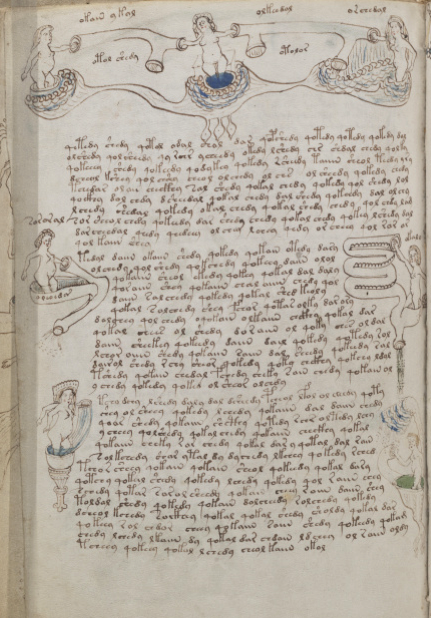

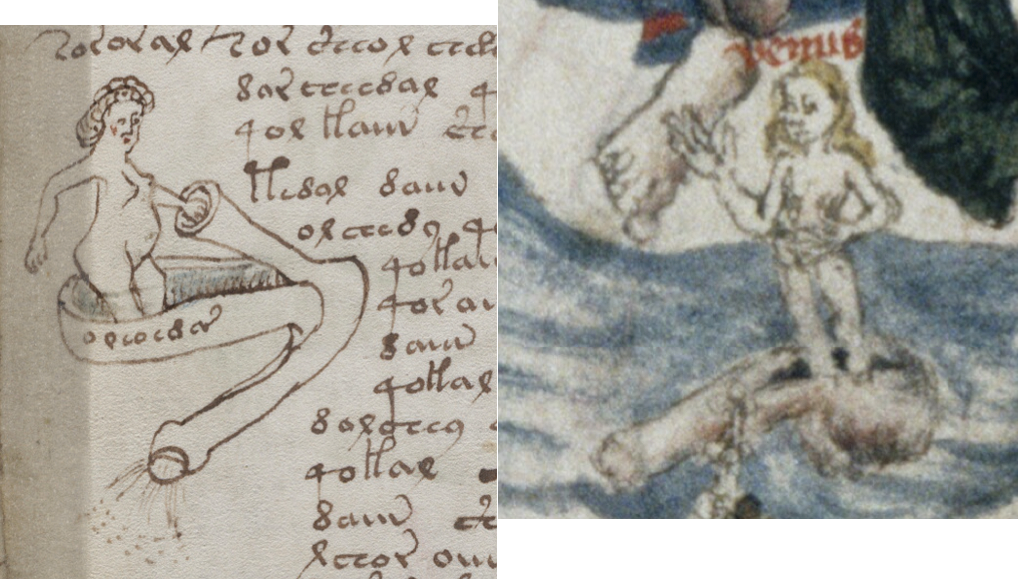

Folio 77v of the Voynich Manuscript always struck me as anatomical. Mammaries and a uterus in the middle, tubes that might be blood vessels or the path between the ovaries and the uterus, something on the middle-right that resembles tubules or a curled intestine and, on the left, a penis with a nymph standing in the testicles, her hand by a “pipe” leading to the penis.

Folio 77v of the Voynich Manuscript always struck me as anatomical. Mammaries and a uterus in the middle, tubes that might be blood vessels or the path between the ovaries and the uterus, something on the middle-right that resembles tubules or a curled intestine and, on the left, a penis with a nymph standing in the testicles, her hand by a “pipe” leading to the penis.

It seems strange, a nymph standing in testicles, but that’s what it looked like to me.

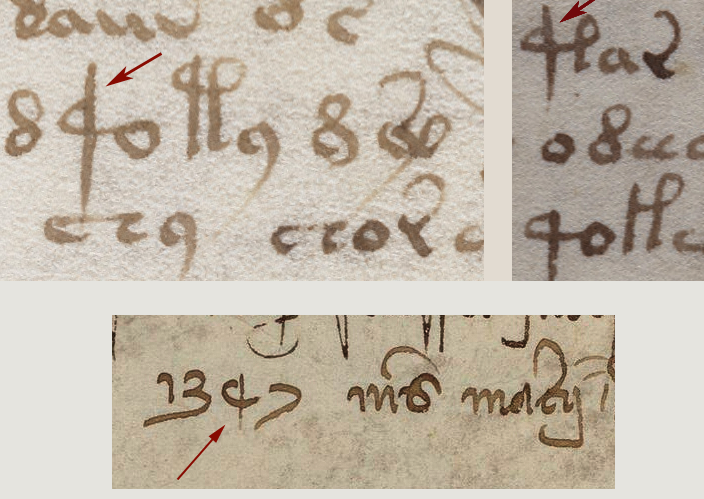

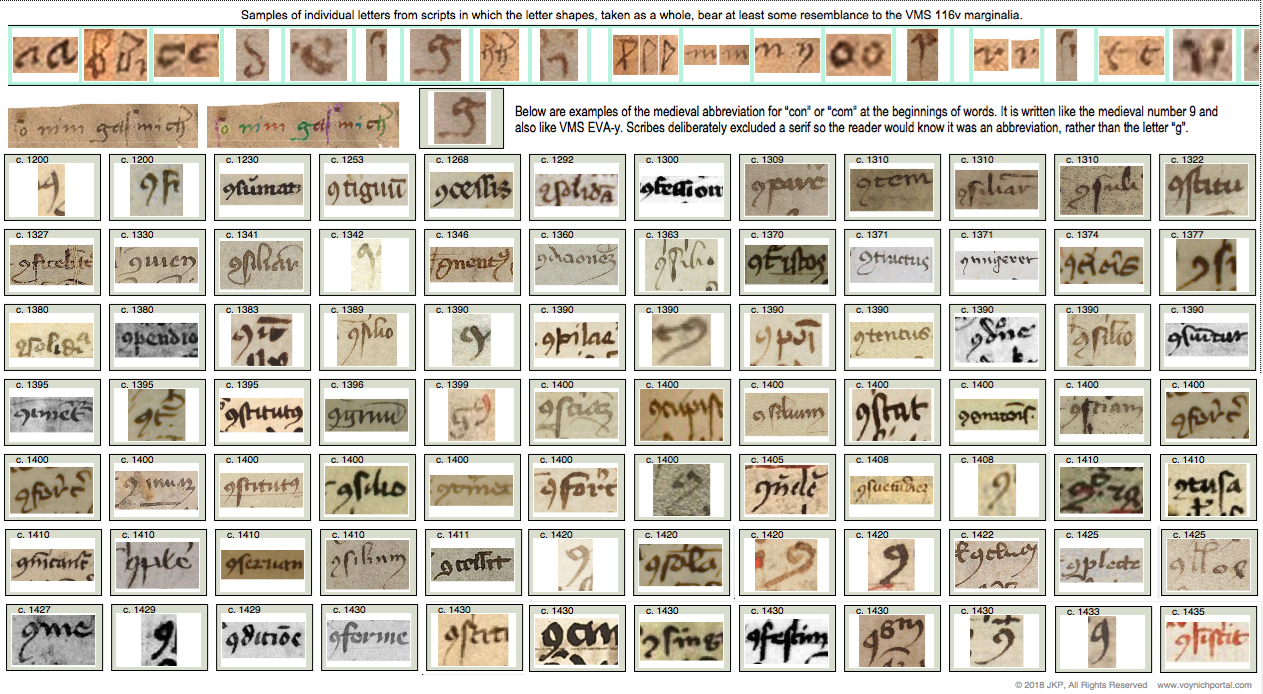

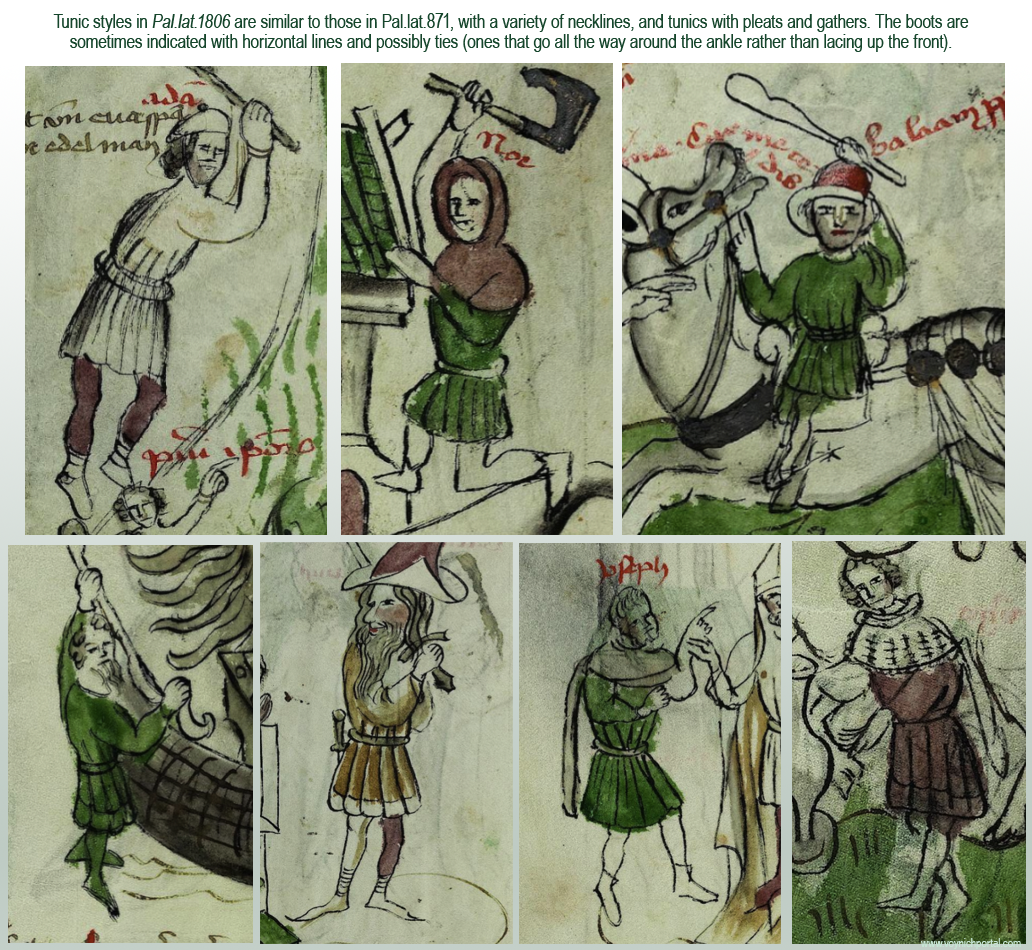

Then, while searching for something unrelated, I came across a detail in a manuscript from the 15th century that I never expected to see.

Illustrated Myths in MS Rawl. B. 214

Rawlinson B. 214 is less than 20 pages, and consists of two-tone compass-drawn charts sandwiched around colored illustrations.

The illustrations are painted in generous shades of brown blue, red, and green. There are Sibyls and gods, including Saturn, Jupiter, and other characters from Ovid’s Metamorphoses, such as Iuno (queen of the gods), Neptunus, and Pluto:

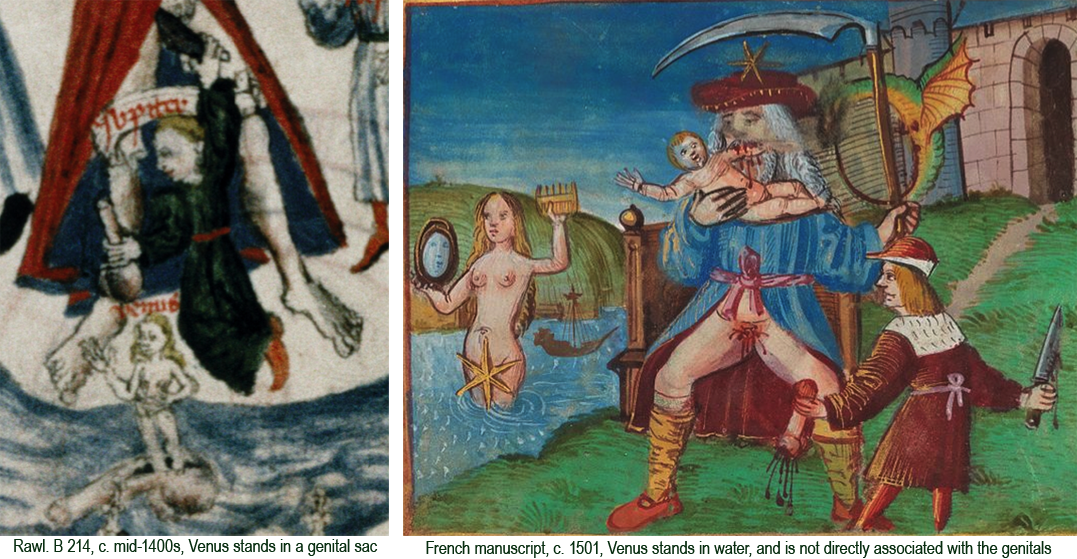

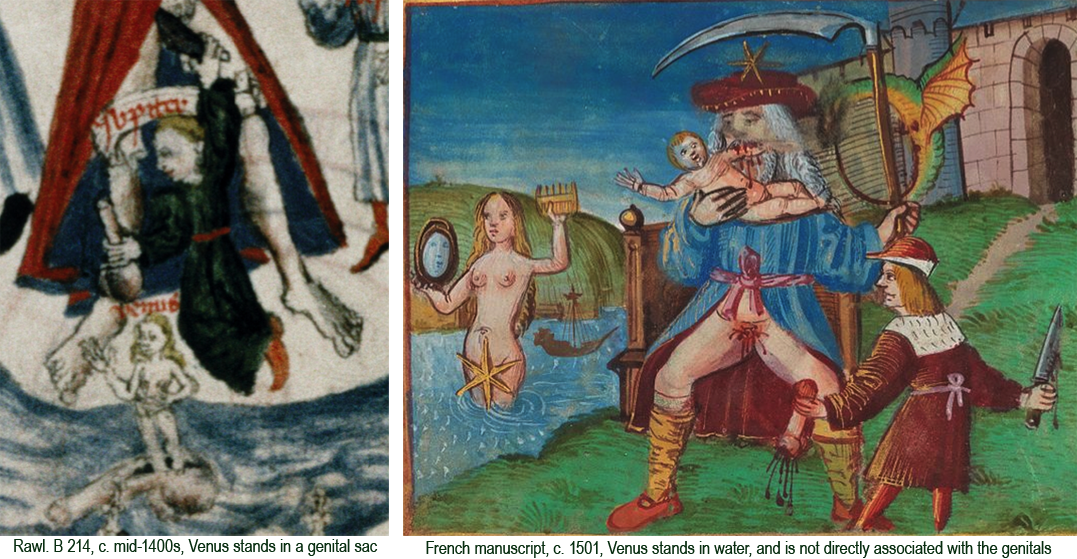

At Saturn’s feet, there is a character that may have particular significance to the VMS. But first, a quick summary of the other pages…

On the following leaf, we see Apollo with a harp and Corvus flying over a laurel tree:

Next to the laurel is a bevy of females, with muses Talia (comedy) and Urania (astronomy) standing out from the crowd. You might notice that Urania is drawn in an appealing way, similar to a few of the VMS nymphs who were drawn with an extra dose of charisma:

Under this is Phiton, a dragon with long ears and somewhat vague wings that reminds me, once again, of the critter in the VMS that is nibbling on a large plant. At first I wondered if this was an animal version of Phaeton (the charioteer), but it turns out it might be a python, and the marginalia mentions “Phiton serpens”. In medieval bestiaries, as illustrated in the previous blog, serpents were often depicted with legs and ears. There are numerous references to serpents in the Metamorphoses.

The following folio has another complex scene in which Venus takes center stage, standing in water, flanked on the left by three naked nymphs. The next page shows Diana with a bow, next to several unlabeled nymphs modestly dressed. Below this, is a rainbow framing Pallas (Minerva). In her hand is a head on a shield labeled “Caput gorgonum” (Gorgon’s head):

Following this is Iuno/Juno with her sight obscured by a cloudband (perhaps at the moment when Jupiter turns into a heifer). She is standing behind another rainbow, flanked by “pavones” (peacocks) whose tails memorialize the hundred eyes of Argus after he was decapitated by Mercury:

Below this, Sybil Bethia rides in a cart.

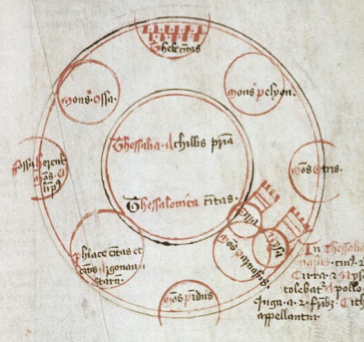

A Change of Style

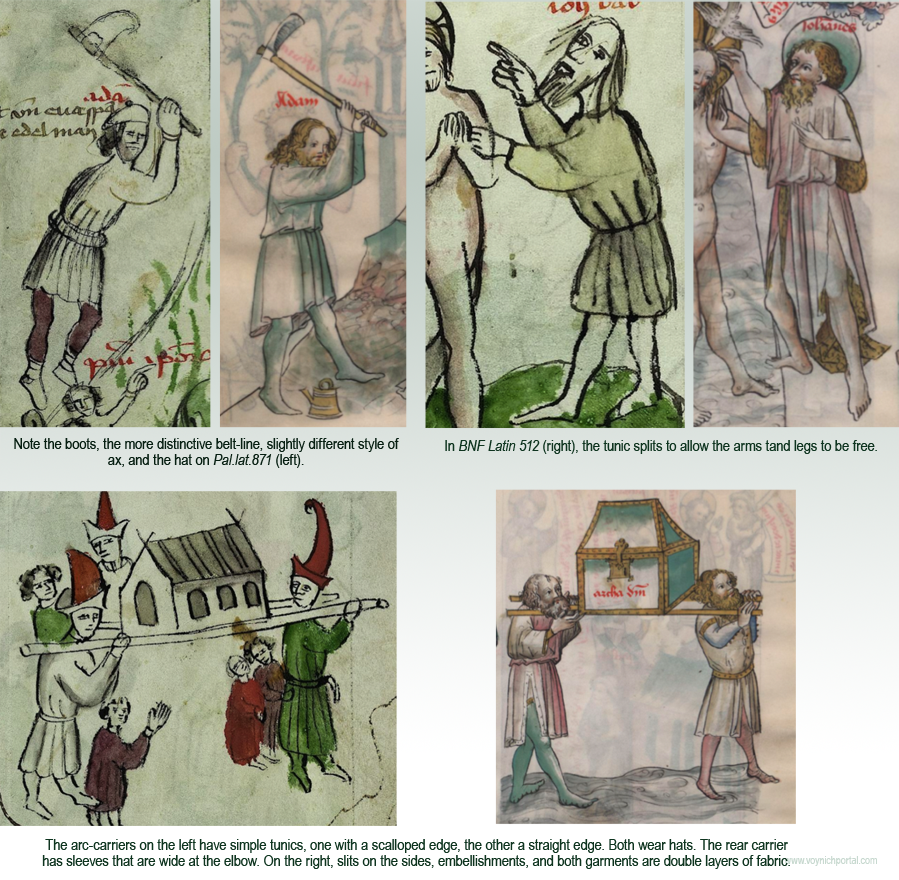

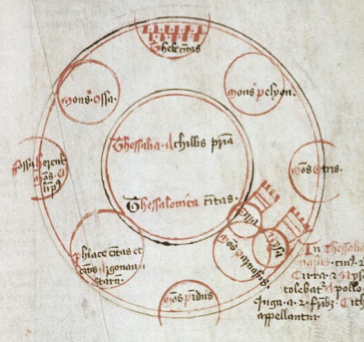

And then the lushly colored illustrations revert to something that could easily be mistaken for a cosmology or geometry chart, but which is labeled with Grecian landmarks, including Mount Pindus, Mount Pelyon (Pelion), and Mount Ossa. These are north of the Greek Islands, as one travels toward Macedonia. It’s a map, in a style quite different from modern maps and more similar to early eastern maps than those of northern Europe.

And then the lushly colored illustrations revert to something that could easily be mistaken for a cosmology or geometry chart, but which is labeled with Grecian landmarks, including Mount Pindus, Mount Pelyon (Pelion), and Mount Ossa. These are north of the Greek Islands, as one travels toward Macedonia. It’s a map, in a style quite different from modern maps and more similar to early eastern maps than those of northern Europe.

After the map, is a drawing that looks vaguely cosmological, but reading the labels tells us it is about literature and philosophy, listing Virgil, Omer, and Ovid, along with muses and poets, somewhat in the manner of Lullian diagrams.

Back to the VMS

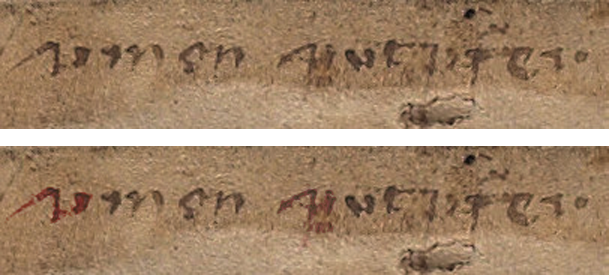

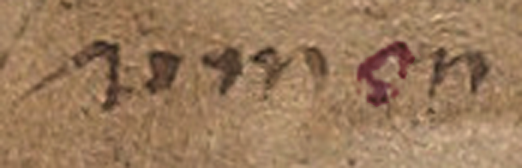

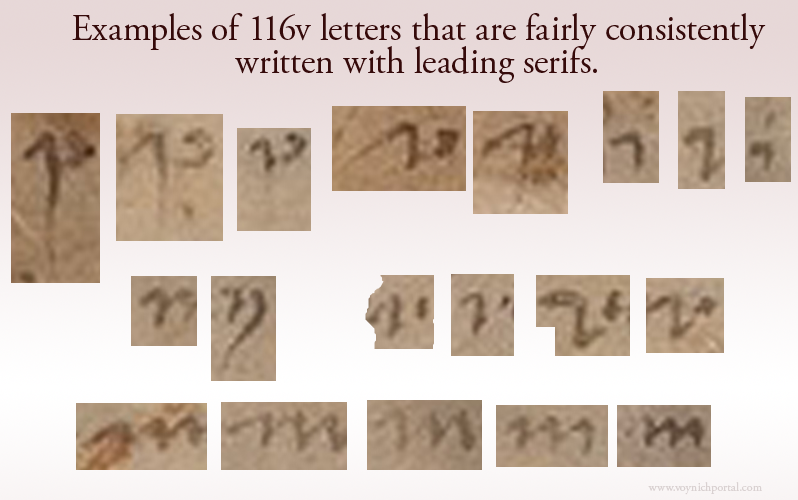

This line-up is quite interesting… nymphs, rainbows, a map in a slightly unconventional style, charts of elements and literature that might be hard to interpret if the labels were in a strange script, and an unusual biological reference that I wrongly assumed was unique to the VMS. When I saw the drawing of Venus in Rawl. B. 214, it instantly reminded me of the VMS drawing on folio 77v, which has always looked to me like a nymph standing in testicles above an ejaculating penis:

It seems unlikely that the Rawl. Venus-in-testes was copied from the Voynich Manuscript, it was created in the mid-1400s, but it could be the other way around, IF the VMS text and drawings were added a few decades after the parchment was processed. But, assuming the VMS drawings were added early in the 15th century, then an earlier textual or visual source might have inspired the explicit drawing.

And then I had an aha! moment…

A nymph standing in gonads. Of course! It’s the classical story of Venus born of the foam of her father’s severed genitals. It might seem a far-fetched way to interpret the VMS nymph if it weren’t for the Rawl. Venus being clearly labeled, clearly standing in a testical-boat, and clearly placed within the context of classical myth.

Can we go one step further? Might there also be an astrological interpretation, as suggested by K. Gheuen’s Konstellations? Maybe. Not only were the classical gods deeply associated with stars and planets, but classical poets were fond of creating alternate stories…

Accounts of how the newly born Venus reached shore vary, but here is one version…

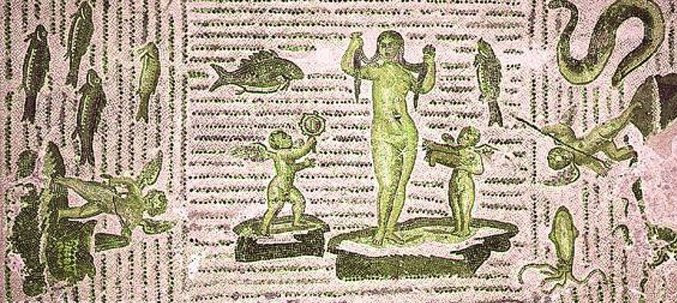

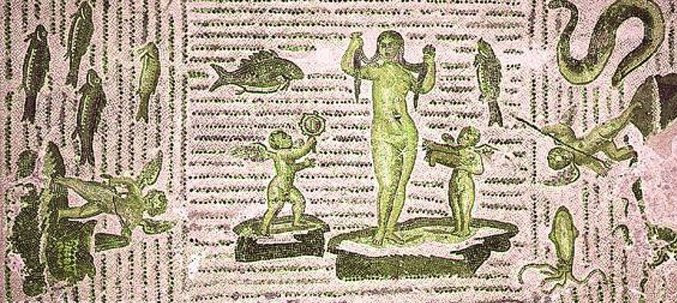

When her father’s godly froth hit the sea and Venus was born, she was aided by fishes, who ferried her safely to the beach and guaranteed their place in history by reigning over her in the sky. The following image may be intended to reflect the environment in which Venus was born, rather than the story of the fishes, but it helps us visualize Venus’s birth. Note the cherub handing her the mirror that became her attribute:

The birth of Aphrodite from a Roman mosaic in the Bardo National Museum, Tunis.

In the Iliad, Aphrodite (Venus) is associated with sexual intercourse, which would make her an appropriate symbol for a biological description of sexual organs or the sexual act. It is thought by some that Hesiod (c. 700 BCE) added or adapted the story of the severed genitals.

But is 77v a clinical description of sex and sexual organs dressed up with classical imagery, or is it classical imagery in the context of ancient myths (without the clinical component)? The difference would influence how one interprets the text.

My personal suspicion, until we know more, is that the drawings on this folio are meant to express biology, with classical myths as mnemonics. I lean this way because plants, astrology, biology, and therapeutic bathing (especially bathing in thermal spas), are all important medieval medical subjects.

Wresting Meaning Out of an Obscure Drawing

The VMS is not exactly like the Rawlinson drawing. It has an extra detail. There is a “tube” by the nymph’s hand. I thought it might be the connection between the seminiferous tubules and the penis long before I realized there might be a connection to classical literature. If there is, then the VMS drawing makes a more direct reference to the biological path for the “froth” by which Venus (Aphrodite) was born (the Greek word αφρός/aphros means “foam” and can also be interpreted as semen).

Usually we see sanitized versions of Venus’s birth (albeit some lovely ones like Boticelli’s). Here is a much simpler 14th-century drawing (right), from an Occitan manuscript—Venus in the surf, holding her mirror attribute. An ancient depiction, from a Pompeiian fresco, shows her lying in a large shell, with a stylus or small scepter, with drapery overhead. In fact, they aren’t necessarily sanitized, they are probably alternate versions in which the semen falls to the sea without the father losing his family jewels. The tradition that explicitly talks about castration diverges from Homer.

Usually we see sanitized versions of Venus’s birth (albeit some lovely ones like Boticelli’s). Here is a much simpler 14th-century drawing (right), from an Occitan manuscript—Venus in the surf, holding her mirror attribute. An ancient depiction, from a Pompeiian fresco, shows her lying in a large shell, with a stylus or small scepter, with drapery overhead. In fact, they aren’t necessarily sanitized, they are probably alternate versions in which the semen falls to the sea without the father losing his family jewels. The tradition that explicitly talks about castration diverges from Homer.

The Cringe-Worthy Version

William Sale suggested in 1961 that the castration myth traces back to the Cyprians, as expressed in a Corinthian terracotta figure of Aphrodite arising from a genital sac, but I had trouble finding examples online, and was hoping to find exemplars more accessible to a medieval manuscript illustrator.

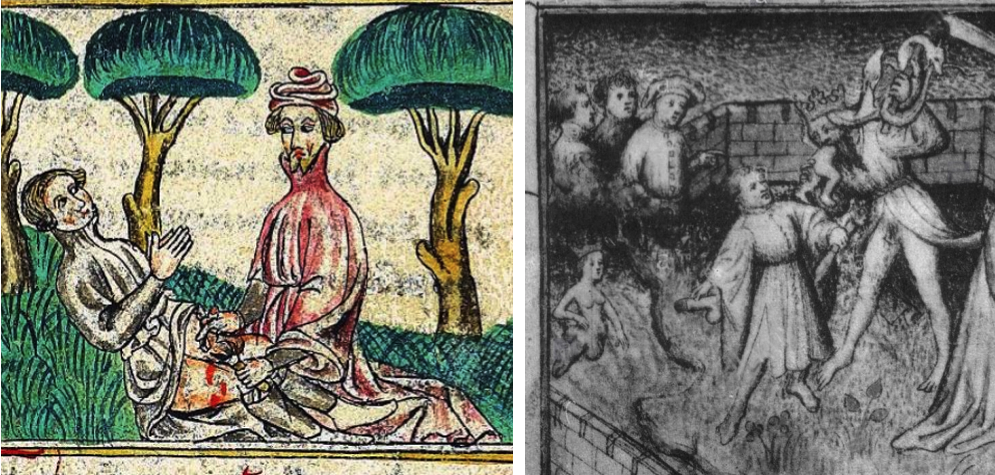

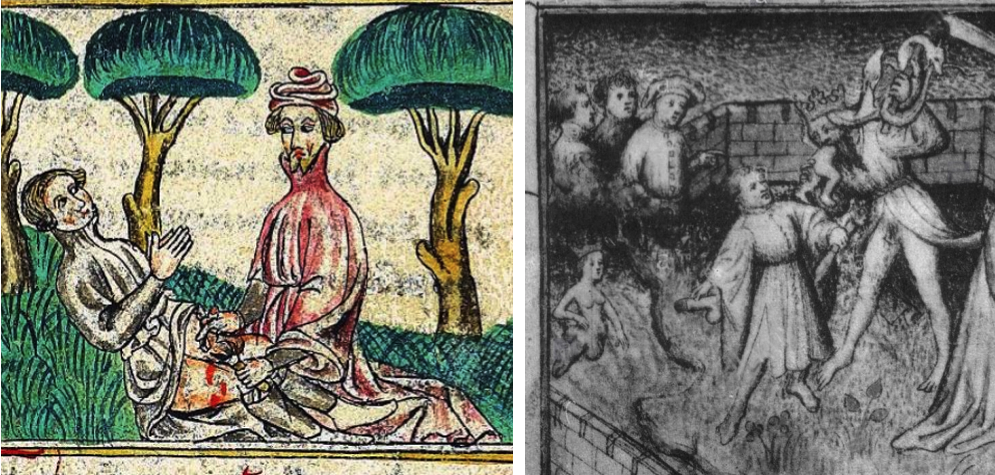

There are gruesome drawings of Cronos castrating his father Uranus, and some where the victim just stares in another direction as though it’s no big deal for your son to whack off your privates (e.g., Bodleian MS Douce 195).

It doesn’t seem necessary to post dozens of examples (which can be found in ceramics, sculpture, manuscript art, and also in tarot cards), as there appear to be three main kinds:

- Cronos/Jupiter castrating his father with no inclusion of Venus,

- Cronos castrating his father with Venus nearby, often in water,

- Venus born from the castrated genitals of her father (as in Rawl. B 214 and possibly the VMS).

Here are examples of what appear to be typical variations, with the less common Rawl. drawing included for reference:

Summary

I was eager to find a possible exemplar for the VMS but one never knows how long it will take. Most of the more common depictions are of French or English origin, but there may be other sources for a theme that dates back to ancient Greece.

If additional images of Venus standing in her father’s genitals were found, or even just one that predates the VMS, it could be a key link in unraveling which predecessors may have influenced its construction.

J.K. Petersen

© Copyright 2018, All Rights Reserve