3 4 March 2019

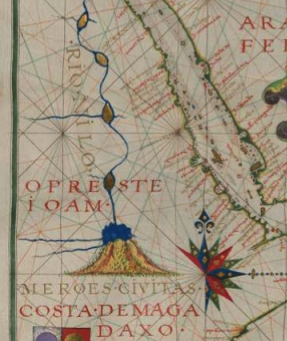

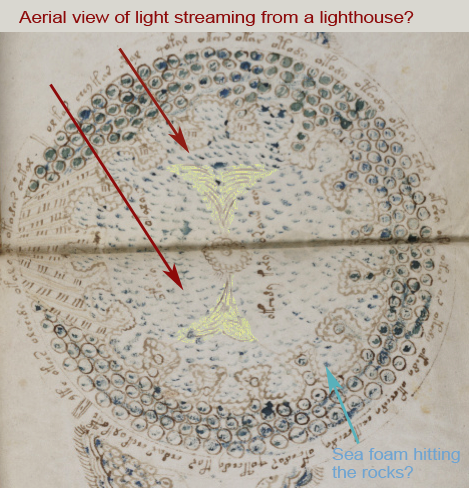

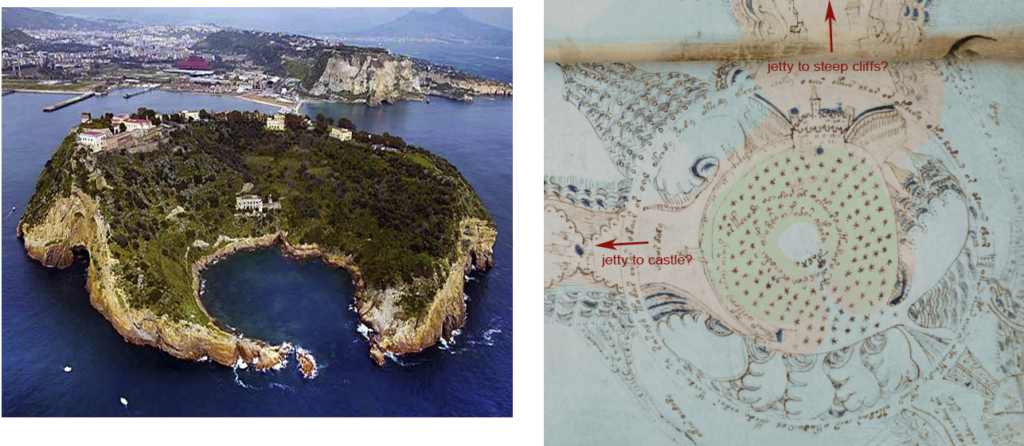

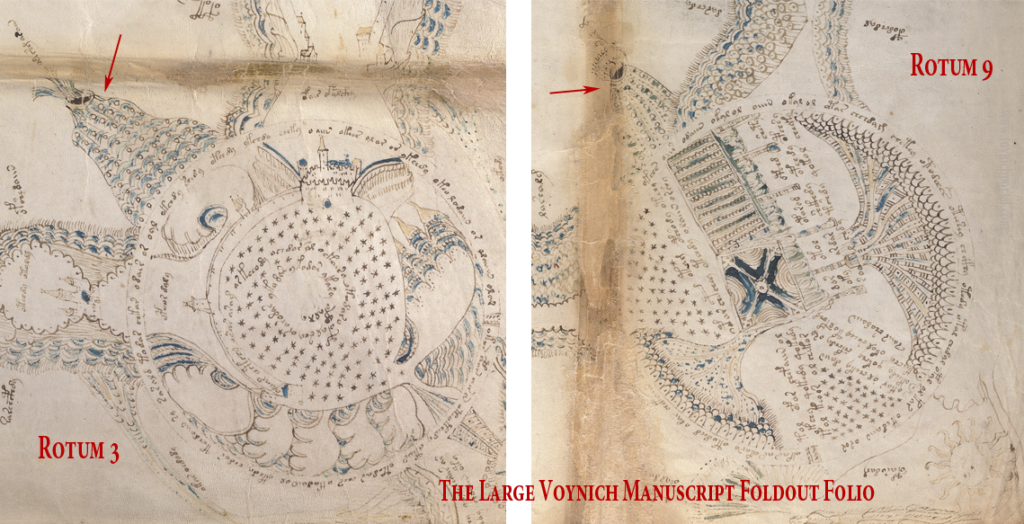

In a recent blog, I described a few interpretations of Rotum 1 (top-left) on the VMS “map” folio. One possibility is an aerial view of a volcano. But Rotum 1 isn’t the only shape that might be interpreted as a volcano. There are other mountain-like structures on the same folio, if one views them from the side instead of the top.

The “map” folio has a wealth of textural structures, too many to describe in a dozen blogs. So this blog will focus on the patterned triangular shapes attached to the sides of the circular rota.

Rotum 3 (top-right) and Rotum 9 (bottom-right) are somewhat different, but the mountain shapes have some commonalities. Both of them are textured, with circles and blue paint in the pattern, both appear to have holes at the top, and both point toward the center of the folio.

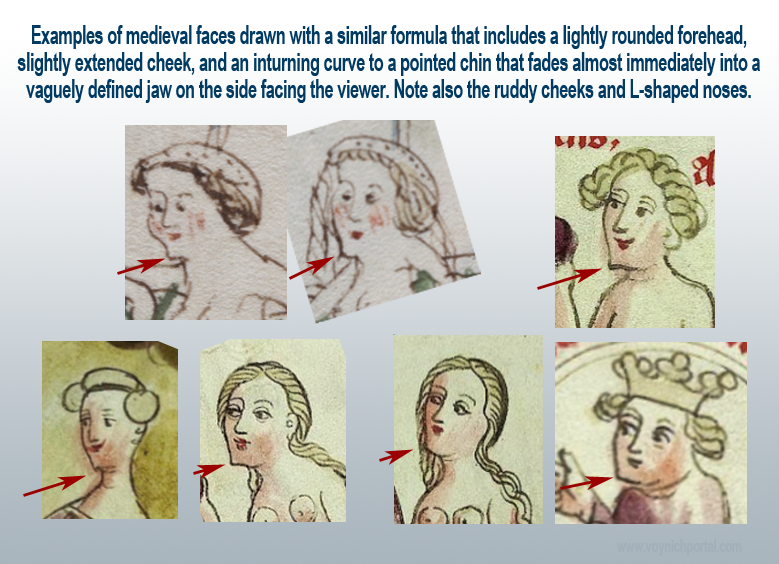

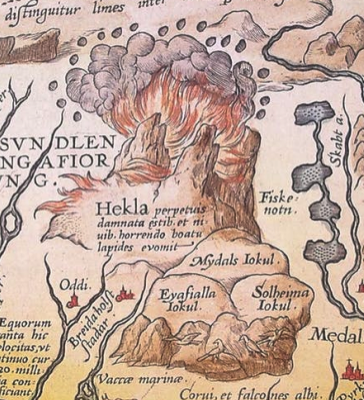

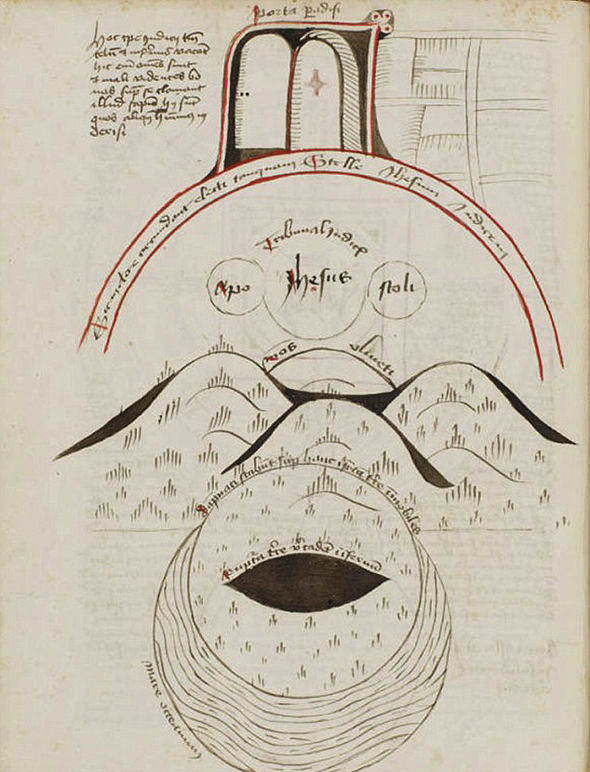

Sometimes bumps are intended to describe rough terrain, rocks, or mountainous regions, as this example from Losbuch (15th c):

But the VMS structures are on the outsides of the circles, are more triangular, and appear to have openings at the ends with something coming out of them:

For years I have thought of these as “spewy things”. But if they were, I wasn’t sure whether to interpret them as horizontal outflows (e.g., exit spouts or natural springs), or as vertical steam vents, geysers, volcanoes, or something else.

It even occurred to me that some of them might be steaming compost piles, which might fit one possible interpretation of Rotum 9 as an irrigated garden:

Details of the Emanations

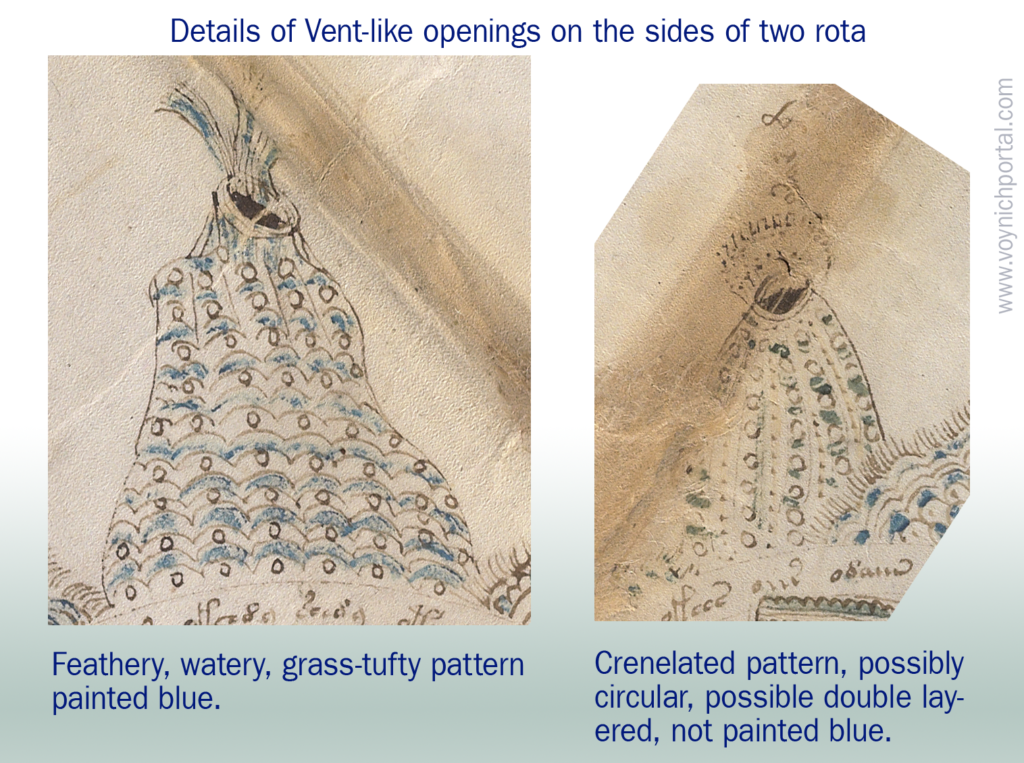

It’s interesting that the protrusions have different patterns, and different “somethings” spewing from the openings. Here’s a close-up of whatever is emanating from the tops:

The one on the left is somewhat watery and free-form, the other somewhat circular, like the splash from dropping a rock in a pond.

The patterns on both bumps are made of circles and lines, but the one on the left is somewhat scaly and lumpy. The one on the right, more linear and smooth on the edges, with alternating small and large dots. Both have alternating sections colored in blue.

Are the textural differences decorative or meaningful? Are there clues on the page to help us work it out?

There are four shorter spewy things between the central rotum and those on each side. They have a simpler scale pattern, but does that mean they are different structures?

I have enlarged and rotated the insets so it’s easier to compare them:

They all connect to the outer rota in essentially the same way. At four points, there emerges a pile of scaly textures with something spewing out. They are not as large as those on Rota 3 and 9 and they are more similar to one another. But the emanations from each has a different pattern. From the top going clockwise, there are

- alternating circles and lines, with a touch of blue paint between the rows of circles,

- alternating bands, some with very light lines with a touch of pale amber, the others with short lines in the perpendicular direction, parallel tick marks in groups of three,

- blank bands alternating with wider bands filled with chevron-style vee shapes, no paint, and

- alternating bands of angled tick marks, each band angled in the other direction, somewhat chevron-like if seen from farther back, no paint.

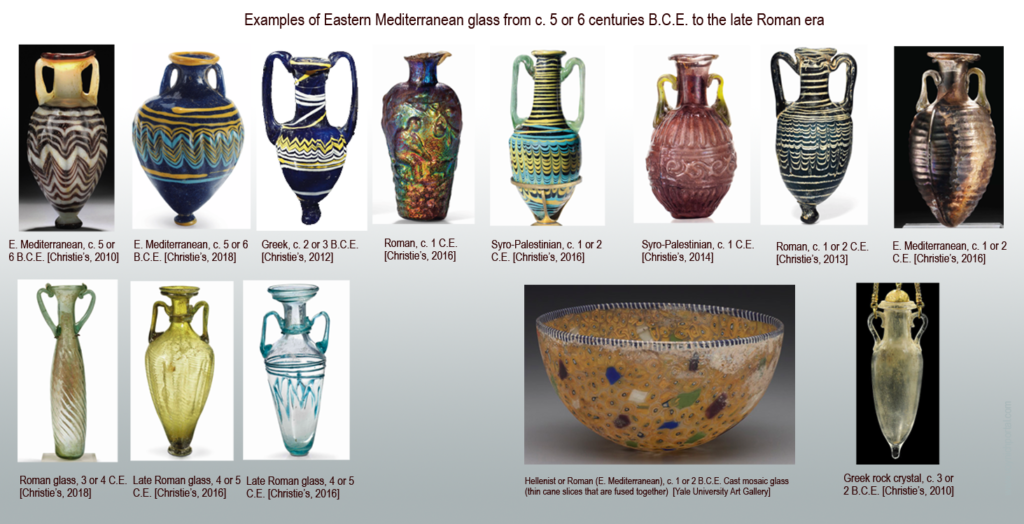

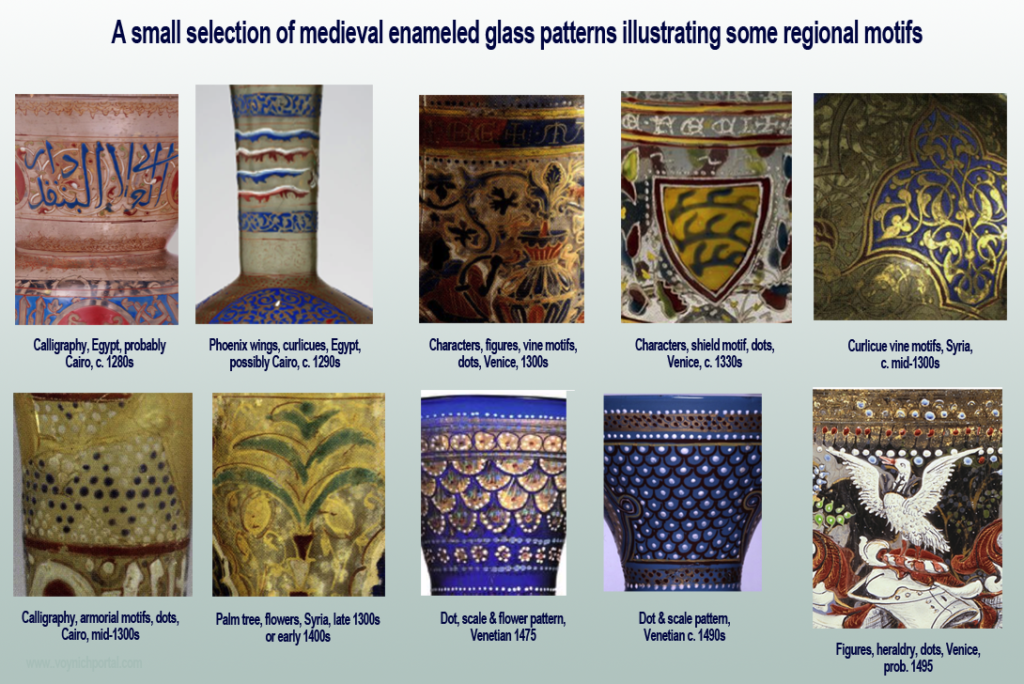

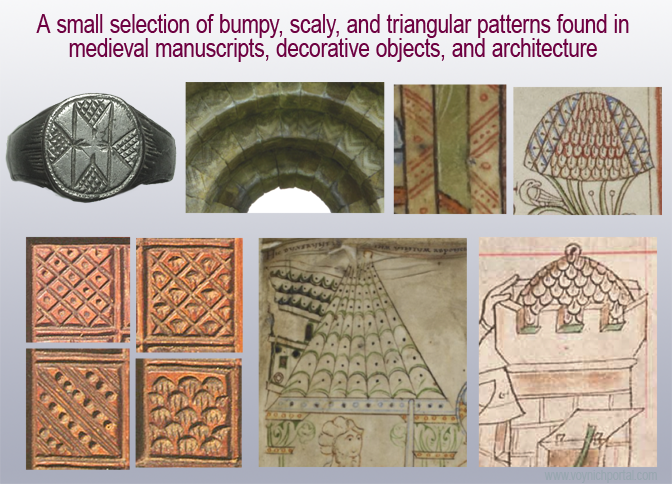

Triangle, chevron, and scale patterns are common to many cultures and go back a long way. They are found in manuscript art, jewelry, and architectural embellishments:

This example from the Beehive tomb in Praesos is more than 2,000 years old:

An Uncertain Context

To me, the central rotum suggests an inverted dome, the kind that is embellished with stars, so I wondered if this rosette might have spiritual significance. The double-scalloped band near the perimeter seems to reinforce this possibility, but since the identity of the central structures is not yet certain, it’s hard to know whether the spewy things are imaginary or real.

I’m also not quite sure how to interpret the pipes. I’ve always wanted to associate them with aqueducts, chimneys, or steam vents, but it’s tempting to think of them as sighting tubes (I’m a gadget freak, so I’m always imagining scientific instruments).

Sighting tubes were in regular use in the Middle Ages, but it would be unusual for there to be so many of them. They’re not all drawn the same, some have smooth sides, with dots around the ends, and come in different lengths; others are the same length, and have a pattern of dots along the length of the tube. Unlike the vent-like structures, they do not spew or connect the rota, and they don’t quite look like chimney pipes. These will have to wait for a separate blog.

I spent quite a bit of time in the early days trying to reconcile the “rosettes” folio with Jerusalem, but every time I tried, the topological features didn’t quite fit. I wasn’t able to reconcile them with mythical New Jerusalem either.

I wondered if it might be a mnemonic map of myths.

Myths, Mountains, and Spewy Things

The interesting structures below are in the Psychro cave in eastern Crete. It has been a sacred cave since ancient times and is associated with the birthplace of Zeus. Some of the textures on the nymph pages remind me of grottoes and caves.

The myth of baby Zeus might fit some of the features…

To save him from being eaten by his father, Zeus was hidden away in a cave and raised by his nursemaid Rhea, goddess of mountain tops and forests.

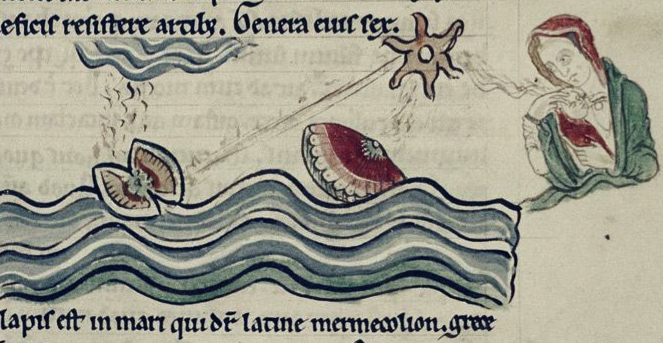

The cave had bees emanating from it that supplied baby Zeus with honey. Sometimes fire was said to emanate from the cave. Could some of the structures with openings be cave entrances? Might some of the spewings be sacred bees or flames?

The interior of this cave has several textural patterns:

Stalagmites don’t spew, but stalactites drip moisture and chemical residues, and are often associated with watery discharges. Could the VMS textures be inspired by cave formations?

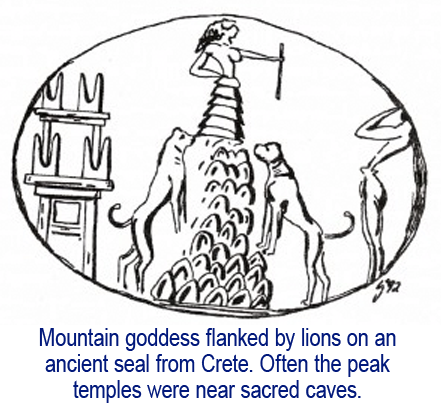

The tops of mountains were often seen as sacred places, and sometimes modified to create temples. This is a Minoan artifact with VMS-like scaly structures representing a mountain:

What if the textured bumps are geological rather than ornamental or mythical…

Natural Structures that Spew

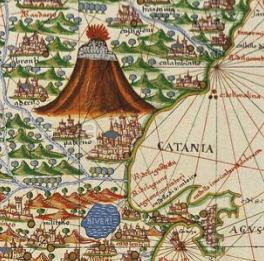

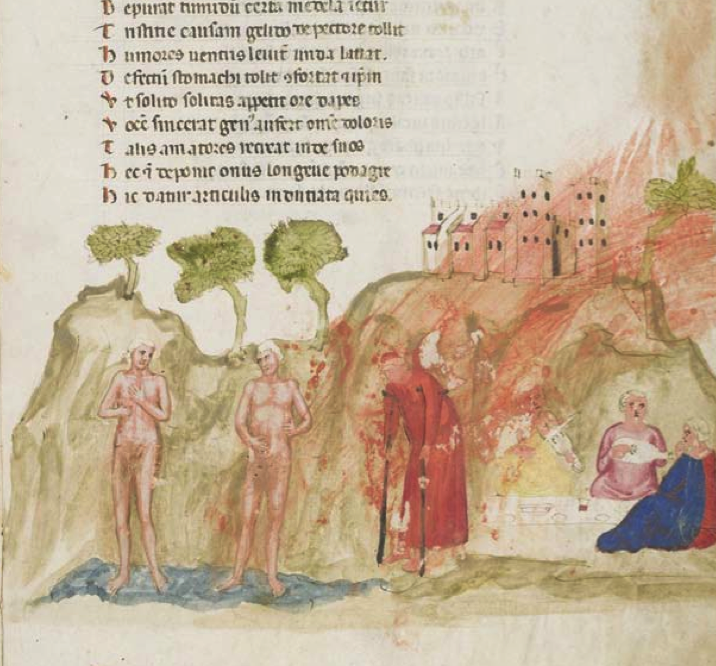

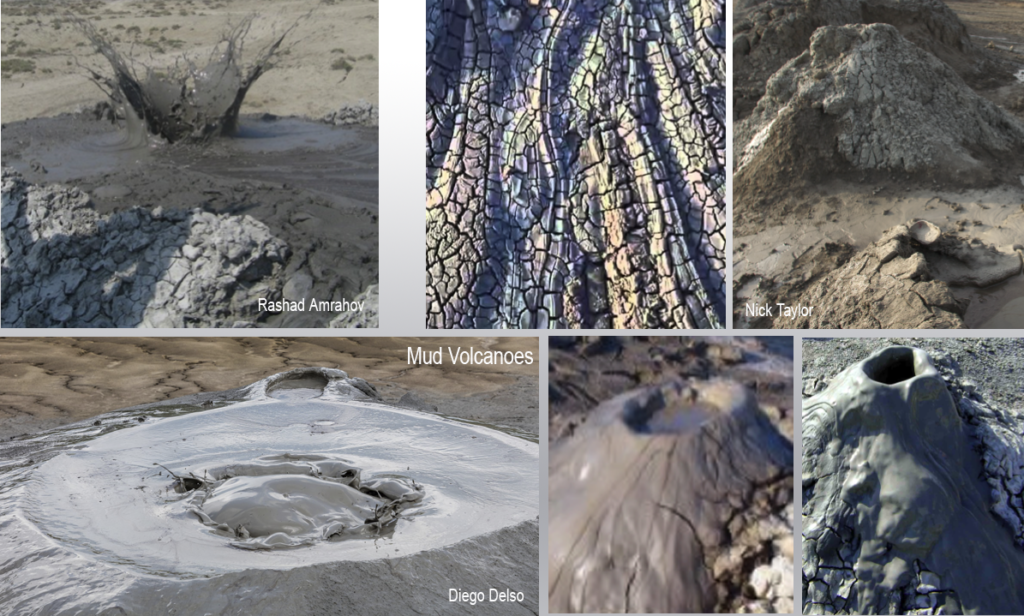

There are volcanic structures that spew gases and mud, and the patterns on the sides can be quite varied. Geologically active areas exist in many regions, including Romania, Yellowstone park, Azerbaijan, China, Sicily, Naples, and some of the spa regions in central and eastern Europe. Even Antarctica has towering gas vents sheathed with ice.

Here are some mud volcanoes. Note the varied textures:

Some mud volcanoes splash, as powerful gas blurps out the mud. Others ooze and slowly drip down the sides. The texture changes as the material dries, and is partly molded by local weather conditions. Could the lumps on Rotum 3 and 9 represent different kinds of mud volcanoes, or two different stages in their formation?

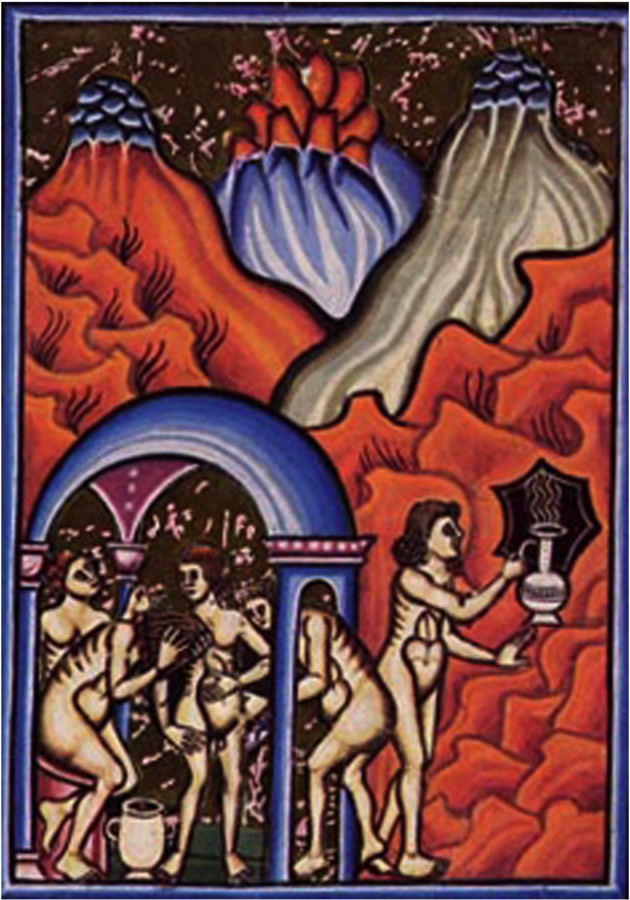

Mud vents would fit well with the bathy themes in the VMS. In Naples and the Aeolian Islands near Sicily, people bathe in mud pools. Cleopatra is said to have enjoyed the mud baths in southeastern Turkey:

Could They be Vapor Without the Mud?

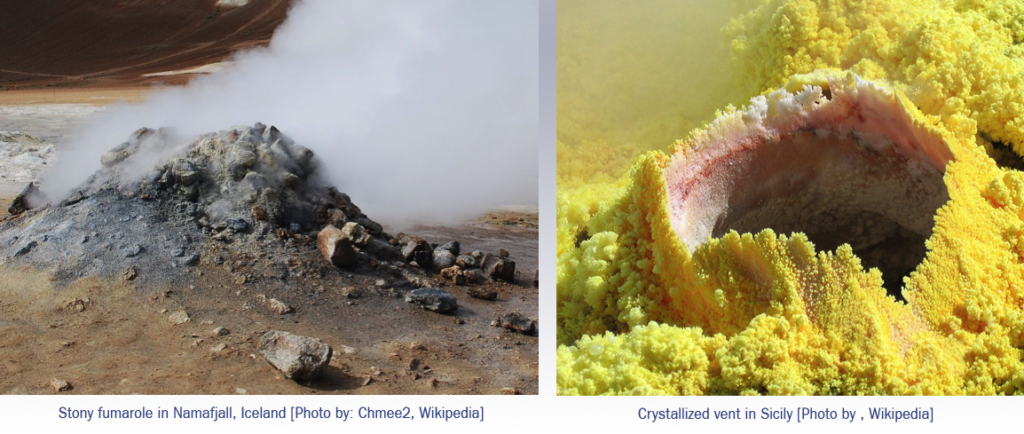

Fumaroles, which emit clouds of gases, vary considerably in shape and texture, as in these Google Image examples:

Sample of Google image fumaroles

A fun fact about fumaroles is that they sometimes blow smoke rings.

I thought the circular formation above the bump on Rotum 9 might be a stylized splash, as in the mudbath image posted earlier, or a loud sound, but perhaps it’s the birth of a smoke ring.

I can’t post this Rights-Managed image, but here is a link, so you can see an example:

Fumarole smoke rings from Mt. Aetna, Sicily.

There are many fumaroles in Iceland, Yellowstone and Lassen parks, El Tatio, Dominica, Naples, and Sicily. These photos illustrate how varied they can be:

Relationships to Other Folios

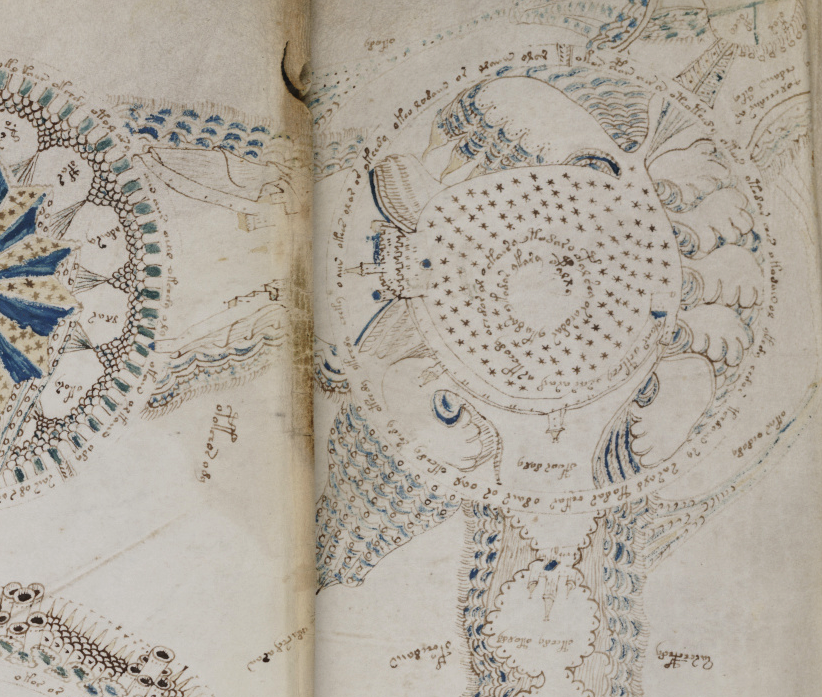

I like to look at things in context and the VMS is more than a map-like foldout. There are textures in the bathy and cosmological sections similar to those on the rosettes folio.

Could there be a relationship between the structures in the VMS “map” and other textural folios like 86v, or do the bumpy textures on 86v represent something completely different?

Is 86v a Different Kind of Information?

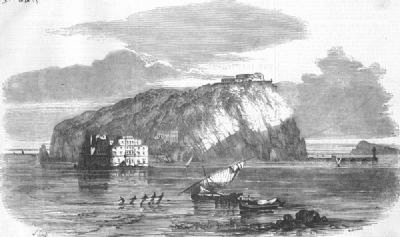

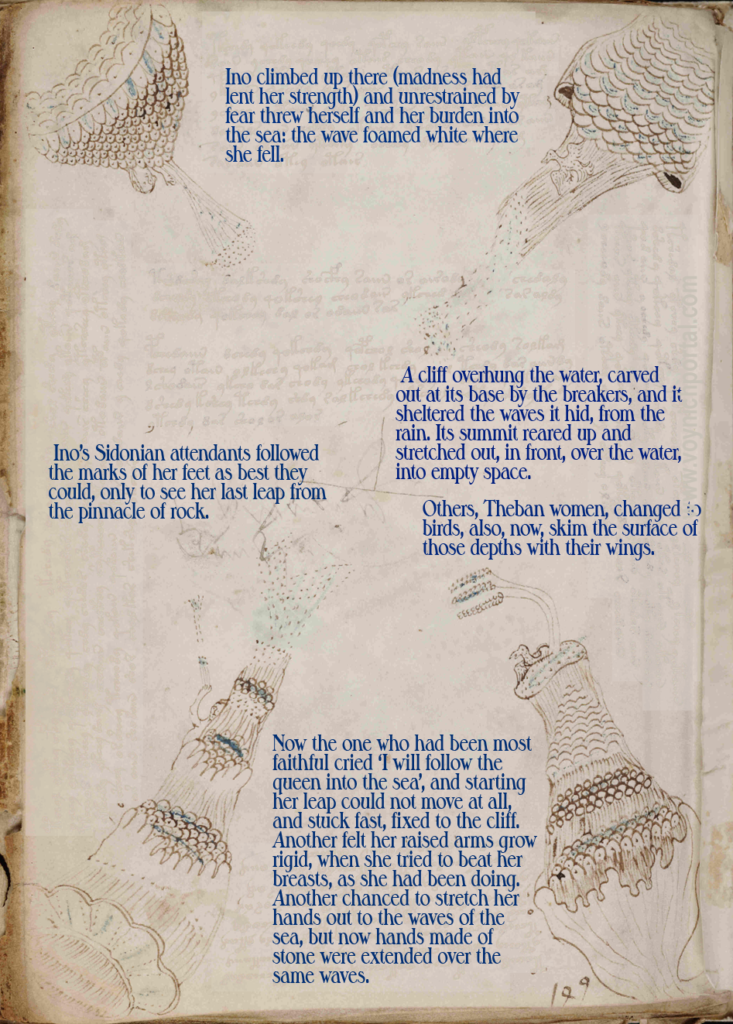

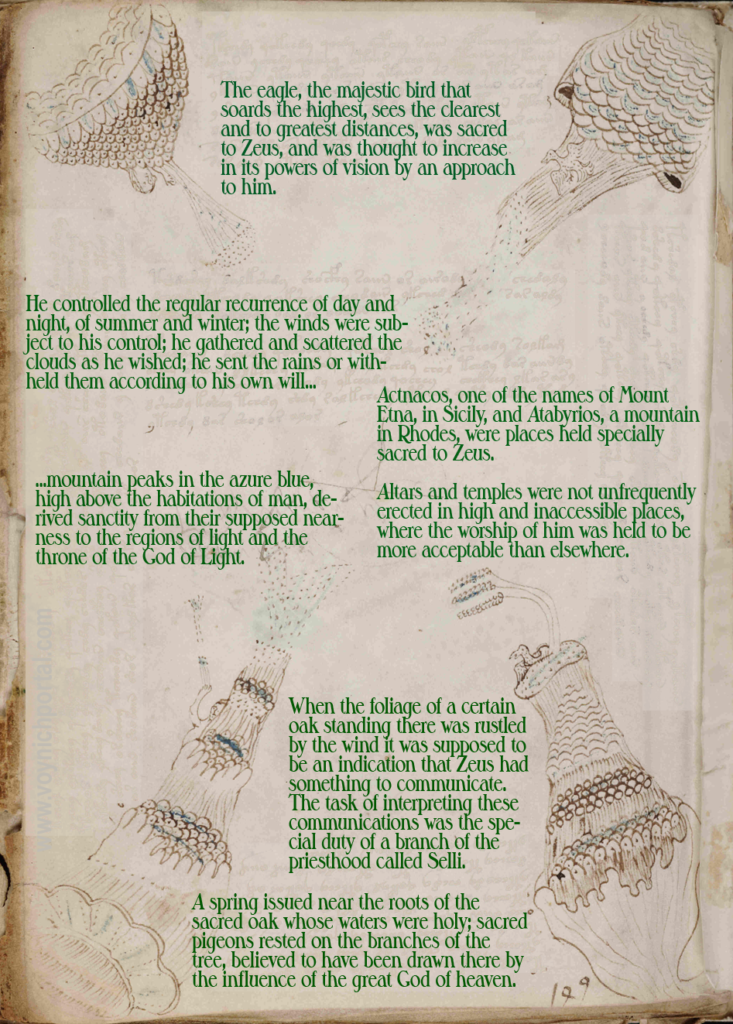

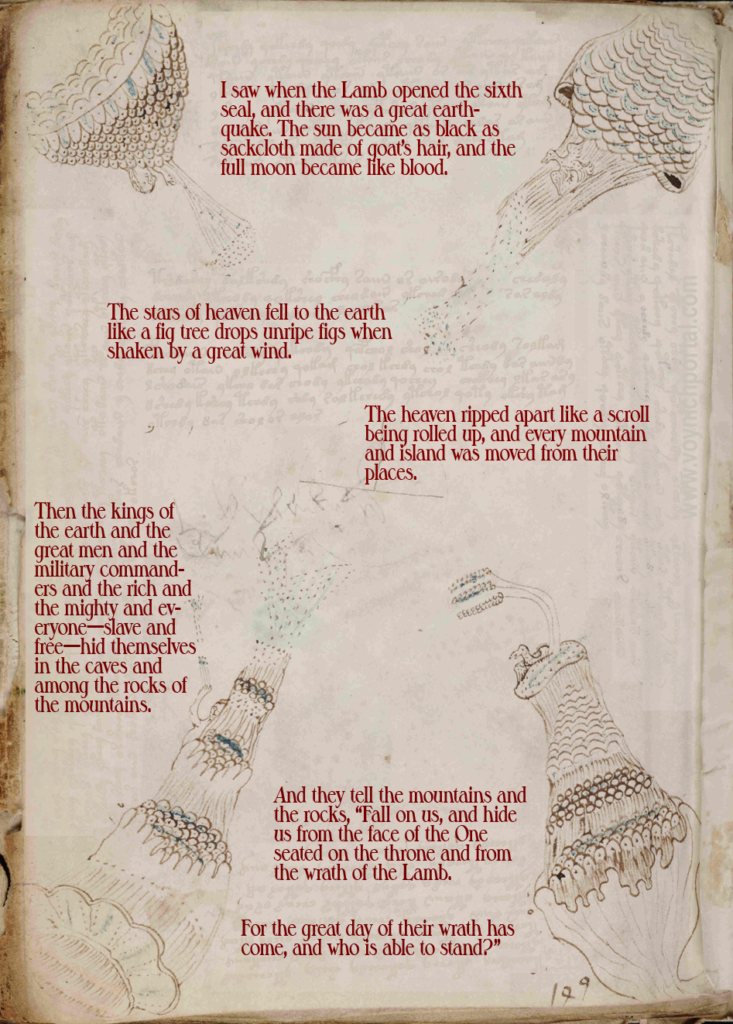

There are textural groups in each of the four corners of 86v, and emanations as well. But it is much simpler, overall, than the rosettes folio, and there are humans and birds on the left and right sides.

The structures at the top might be weather-related or celestial (assuming this folio has a “top” and a “bottom”). Those at the bottom resemble stylized mountains or island tors. They are quite dynamically slanted toward the center, slightly off-kilter. One of the humans appears to be hiding. The VMS rosettes folio has an explanatory, practical feel to it. This one has a more narrative feel.

If it is narrative, can we guess what it is?

I have a lot of ideas about this, but I’ll choose three as examples…

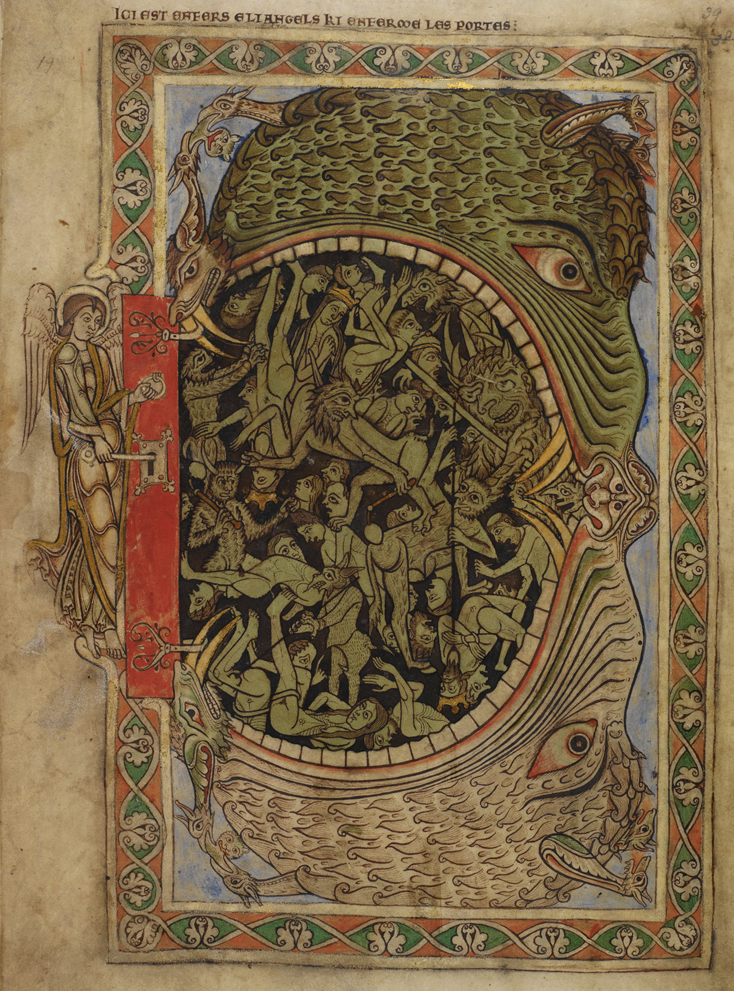

Here’s one possible interpretation, according to an ancient myth:

But there are other possibilities, like this one:

Or perhaps something like this:

The last one is based on the book of Revelation. It describes the cataclysm that occurs when the Sixth Seal is opened.

Apocalyptic scenes of the Sixth Seal, like the one below from Getty Ludwig III 1 (c. 1255), traditionally show the sun and the moon and sometimes a cloud-like division between heaven and earth. The heavenly bodies drop stars like figs (note the star shapes and snowball shapes). The people hide in the mountains (often there are two mountains resembling giant termite mounds, one or both with a tree):

This more traditional image is stylistically different from the VMS, but ignoring the style, the enigmatic 86v has some of the same narrative flavor as other medieval illustrations.

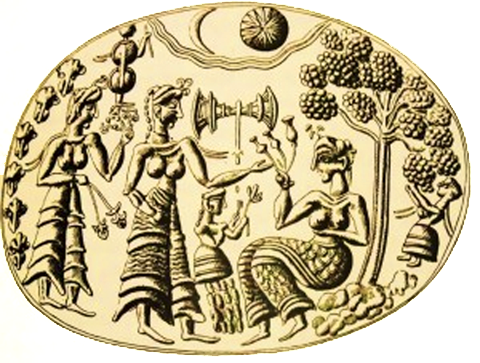

As a side note, the theme of sun and moon within a defining cloudlike band is very ancient, as in this pre-Hellenic Minoan artifact illustrating rites in a sacred grove (notice also the many textures):

The same sun/moon/cloud-band motif can be seen in the 12th century Eadwine Psalter (which I’ve discussed on the Voynich.ninja forum):

The Eadwine Psalter has some elements similar to 86v, including emanations from the heavens, and trees, birds, and hilltops:

Note how each wall has a different pattern, even though they are essentially the same kinds of walls. Is this what is happening in the VMS, or are the textures meant to convey differences?

In the VMS, I get the feeling that the varying textures in the big bumps on the “map” folio and those on 86v represent different (or somewhat different) things. The patterns in the emanations from the smaller bumps however (the ones in the insets), might be purely decorative.

Summary

One blog can’t even begin to introduce the subject of the VMS textures—this only scratches the surface. The important thing to remember is there are many ways to interpret the same drawing, and it’s not enough to look at one folio, others should be considered as well..

J.K. Petersen

© 2019 J.K. Petersen, All Rights Reserved

Postscript 6 March 2019: I mentioned termite mounds in my article, but forgot to include the picture and search link.

Termite mounds are quite sophisticated and diverse in size and texture and some of them resemble the ventlike shapes in the VMS. Some even have regular patterns of holes around the sides. They don’t “spew” from their tops, but if the VMS mounds are meant to be horizontal rather than vertical, then the entrance and exit of insects, like termites, ants or wasps, might be represented by a variety of textures pouring out from a hole.

Google image search for termite mounds

Wasp holes do sometimes “spew” insects from their tops. Here is a link to some examples:

Google image search for wasp mounds

Google image search for ant mounds

Even certain birds, like the brush turkey, will build large mounds

Clearly there are quite a few natural structures, large and small, that could be expressed by textured mounds with openings.